Listen to the Squawking Chicken: When Mother Knows Best, What's a Daughter To Do? A Memoir (Sort Of) (8 page)

Authors: Elaine Lui

And then family obligations interfered. Dad’s oldest

sister, Sue, who was the third child in their family of ten, had immigrated to Canada with her husband. There were fewer opportunities in Hong Kong for his siblings, and many of them were hoping to follow Sue’s lead and build their futures overseas. Sue was now settled in Toronto with three children and ready to help other family members. According to my ma, Dad was Sue’s favorite brother; she wanted him to come over first, even though my parents had no complaints about staying in Hong Kong. They were better positioned than the rest of Dad’s family and weren’t looking to relocate. Ma’s life was leisurely. When Dad went to work, she’d go for dim sum with her friends and then play mah-jong until it was time for dinner. They had a housekeeper. On weekends, they’d leave for romantic getaways on Lantau Island or Macau, just short ferry rides away. Dad had found his princess and she was introducing him to experiences he never thought he’d have. Ma finally found someone she could trust completely, and he was her family now. But Ma claims that Dad’s family, the Luis, believed Sue would be discouraged if Dad turned down her offer, and that she’d be hesitant to extend it to anyone else. Dad felt pressured to follow Sue’s lead to go to Canada and Ma didn’t fight it. In that generation, women followed their husbands and, besides, Ma was no longer contributing financially to their home. In the end, my parents decided to do what was best for the rest of the

family and packed up to go to Canada, to start over in a new country. “I was just twenty-one years old,” Ma told me in the coffee shop, still stirring her coffee that had long gone cold, the spoon caught in her long red nails spinning around and around.

Ma went from being a pampered housewife in Hong Kong to working two jobs in Canada. Suddenly she was scrubbing dishes at a restaurant, those nails now chipped and softened, and trying to understand English. Nobody showed her to the best table at dim sum and there were no more afternoon mah-jong games. Nobody recognized her at the grocery store. She had nowhere to go but to work and back, and eventually she even took on a second job waiting tables.

But she had reinvented herself before. She was the phoenix who rose from the ashes of her rape. And her phoenix-like characteristics served her well again here, not unlike many immigrants who find themselves in new countries, shocked by a new culture. She was adaptable. She learned how to drive on the other side of the road. She went about creating a new circle of friends with the local Toronto Chinese community, mah-jong their uniting force. (Ma has a radar for mah-jong. She can sniff out a mah-jong player within a fifteen-block radius.) She and her friends would go shopping for North American goods to send back to Hong Kong,

writing to friends and family about her new and thoroughly modern Canadian lifestyle. The Squawking Chicken takes over Canada! No matter how hard it actually was, back home they would never know. Back home the Squawking Chicken’s mythology was intact.

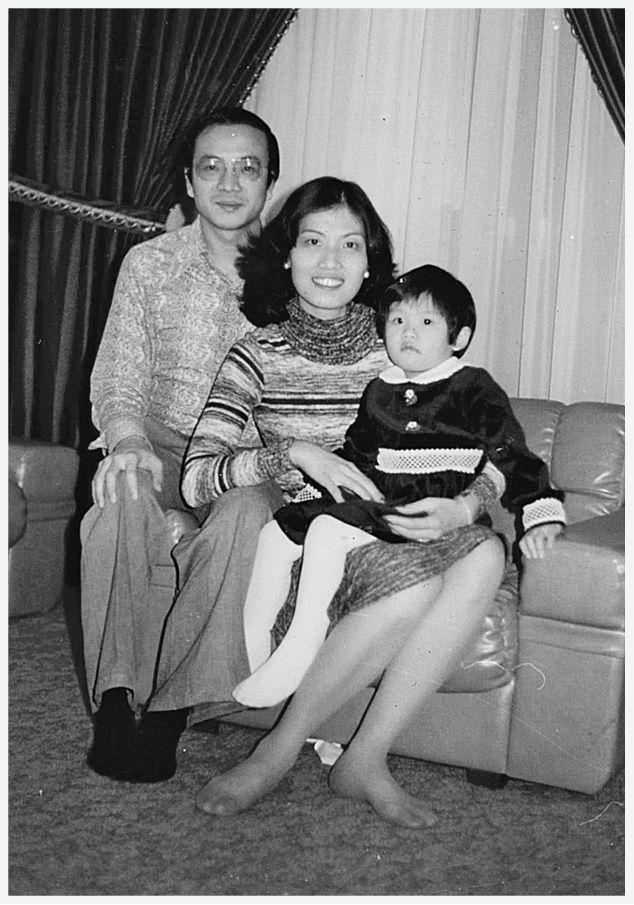

I was born two years after my parents’ arrival in Toronto. Ma said she knew I’d be a big baby because one day she ate a bowl of cherries and she could feel a new set of stretch marks extending across her belly.

“From the very beginning, Elaine is always wanting more,” she likes to repeat, whenever people ask her about how big I was as a baby. “She make my stomach so ugly.”

Ma delivered me at 1:23 a.m. under the sign of the Ox. Ma said: “What’s an ox usually doing at one o’clock in the morning? Sleeping, right?” Toronto is twelve hours behind Hong Kong. Had I been born in Hong Kong, it would have been the middle of the day, when an ox is expected to be hard at work in the fields. Ma took this opportunity to credit herself, again, for giving me an easy life, as if she had always planned my nocturnal birth.

During this time, the rest of Dad’s family started settling in Canada. His parents were among the last to arrive. They came shortly after I was born. Ma recalls that there was a family summit to decide where my grandparents would live.

Everyone had an excuse about why it wasn’t convenient for them to take in my grandparents until they were able to secure permanent residency. In the end, the responsibility fell to my parents, and they moved out of their cozy apartment and bought a bigger house to accommodate the older generation. Filial Piety was at work once again. Ma believed it was their duty to take them in.

So Ma went back to work when I was just a few months old. By then, she was working full-time at a hardware store and then driving downtown to wait tables at a hotel. She’d leave me with Dad’s parents and return home well after I’d been put to bed. The new house was an ambitious purchase. Dad had to put off his studies to make enough hours in the accounting department of a computer company so that they could keep up with the mortgage payments. He was frustrated that his life plans were constantly being rerouted because of the demands of his family. Ma was the one, between them, who rationalized their decisions, who refused to indulge in bitterness and instead kept them focused. She found herself in a familiar position. Just as when she was a young girl, she was looking after everyone else and feeling unappreciated.

And it turns out she was an easy target. The Squawking Chicken was the Squawking Chicken: loud, outspoken, honest. She was not like the other Lui wives and daughters, relegated to the corners of the room while the men stayed in the center. The Squawking Chicken belonged in the center too. But the Luis were intimidated by Ma’s behavior and style of communication. Ma came to realize, too late, that they lacked confidence and were therefore threatened by hers. They misinterpreted her volume for arrogance. Their insecurities prevented them from seeing that Ma was always well intentioned. It’s just that they couldn’t get past the voice . . . and the nails.

One night Ma was summoned into her living room after she’d come home from work, tired and hungry, to answer to charges from my uncle. My grandparents were upset that they were being forced to babysit me, and Ma’s attitude wasn’t grateful enough. She was ordered to kneel and apologize. In her own home, a home she struggled to pay for, a home that she bought so that her in-laws could be comfortable, even though it meant taking time away from me, her only child. At first, Ma refused. But she had no support. Because Dad could not act. Shamed by what he believed were his own inadequacies, and unable to overcome his insecurity and weakness—the same characteristics he shared with his kin—he was, then, a man incapable of defending his wife. He stayed in the basement, smoking, hating himself

but paralyzed by fear. Without an ally, without anyone to have her back, the Squawking Chicken had no choice but to drop to her knees. Dad’s inaction rendered Ma powerless. For the second time in her life, she’d been betrayed by family.

My parents’ marriage deteriorated after that. For the next six years, the Squawking Chicken was silenced. Until one night, after a brutal fight with Dad, she realized it was time to set herself on fire again. The phoenix was molting. She had given his family everything and there was nothing left. Not even me. She was bitter and desperately unhappy, to the point where her health had started to decline. She had no

savings. She had no prospects. There was no way she could take me with her. She felt she had no choice but to go back to Hong Kong, alone, without me, not wanting to disrupt my life or compromise the better opportunities I would have in Canada. It was a heartbreaking, excruciating decision, not only because she had to let go of me temporarily, but also because, after all that had happened, she was still in love with Dad. But the situation had become impossible. On the day of her departure, she told Dad two things: “I will fuck you up if you fuck up our daughter.” And “I will come back to you if you make something of yourself.”

And then she was gone.

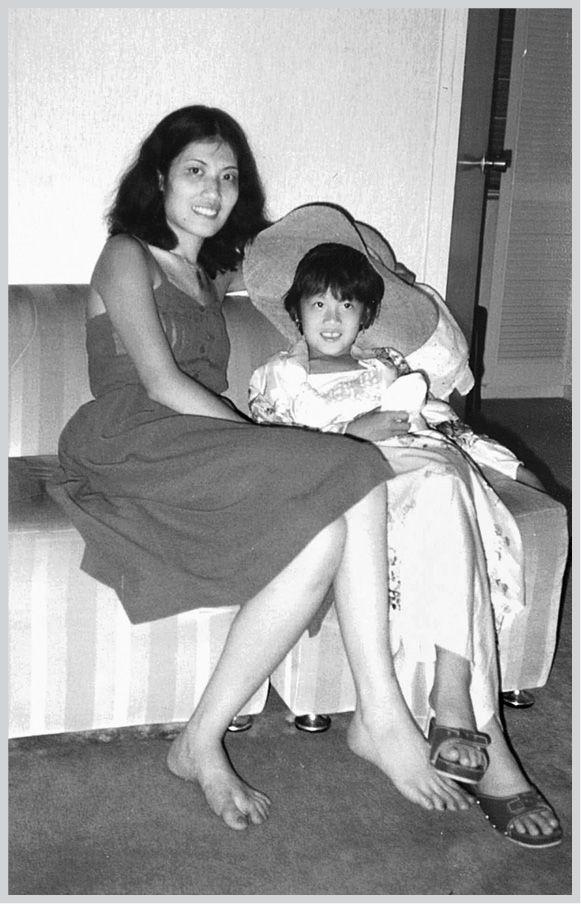

While Dad and I were adjusting to our lives without her, Ma was rebuilding hers in Hong Kong. She started dating my stepfather the following year after she and Dad had officially divorced. He was kind and generous and he promised her that he would provide for me too. After years of struggle, after being put down by my father’s family, after shouldering her own family’s scandals, she was finally allowed to be comfortable. She sent for me as soon as she had settled. It was decided that I would live in Canada with Dad during the school year but that I would spend all holidays with Ma and my stepfather in Hong Kong—two weeks at Christmas, two weeks during spring break and the entire summer. My stepfather was indeed as kind and generous to me as he was to her. He kept his promise.

“What do you think of your accusations now?” Ma asked me when she finished her story. “If you want to say I fucked off with another man, who do you think I was doing it for?”

Sitting across from her that day in the coffee shop, after listening to Ma confide to me the rationale behind her decisions, and the sacrifices that had preceded them, I finally understood that she left me

for

me. That in doing so, my father became more responsible because he was now responsible for me. That having to raise me by himself was the motivation he needed to make something of himself, and he

did. I also understood that in the end, she was proud of Dad and of what he had accomplished.

“I regret nothing,” Ma concluded. Because in doing what she did, I was better for it.

Then she finished her coffee and went off to find the rest of our group in the mall, leaving me to think about what I had just learned. It was a pretty theatrical exit. She wears her watch loose on her wrist so she’s always shaking it so that it’ll fall back into place. She shook it extra vigorously this time when she got up out of her seat, stretching her fingers out wide so that her hands seemed even longer with the added length of those long red nails. Then she tossed her hair back and walked deliberately out of the shop. Very Old Hollywood. Looking back, it was like a performance she’d been rehearsing for a long time. At that moment, though, I felt bad. I knew I had fucked up. But at the same time, I also felt like I had just met my ma for the first time. And it was the first time I felt the surge of real, mature love—not the cuddly kind of love you have for the mommy who takes care of your basic food and water needs, but the profound kind of love for the mother who shows you how to be a real person. This love is an exclusive understanding between two people who have always been connected, who will always be connected. I didn’t know consciously then, but I can tell you now that that was the seed of awareness: that my relationship

with my ma will be the greatest, most important relationship I will ever have in my life. And I wanted to thank her for it.

Using the money I had originally intended to spend on that dress, I went instead to the jewelry store. I could only afford gold hoops. Gold because it was her favorite. Then I went to find her. She was waiting by the mall exit with the rest of our group. I presented them to her in front of them. I apologized for my behavior and told her that to make up for my poor attitude and the horrible accusations I wanted her to have the earrings. She picked them out of my hands, those red nails slowly, ceremoniously separating the clasp, attaching them to each earlobe.

“Do you like them?” I asked her.

“Do

you

like them?” she asked me back.

I said I did. And she said, “Good. It doesn’t matter if I like them. But it matters that you like them. It matters that you like and remember the times that you thank me. You will be thanking me for your entire life.”