Listening In (36 page)

Authors: Ted Widmer

JFK:

What about … it’s really sort of ironical to go through these experiences, talking to both of us. [unclear] Especially when I’m sure when he’s dealing with the Chinese, who are hopeless, and I’m dealing with [unclear] and Nixon, and the rest of these people, who are almost hopeless.

COUSINS:

The political situation is somewhat the same, it’s interesting.

JFK:

Agreed. He does seem to feel he has a complaint; I don’t think he has one, but he thinks he does, and that’s the important thing, not whether I do. But it seems to me when we came down, the Senate had indicated that we might even go down to six,

1

perhaps even five, it wasn’t, wouldn’t have been a hell of a concession for him to go up to. Unless he’s in very much more trouble than I am. I don’t think probably it would get by the Senate anyway, even with six, but at least I wouldn’t mind making the struggle, as I said to you before. But his control must be very limited if he can’t go from three to five.

COUSINS:

As I say, on a personal level, having had the men on the council say, well, Nikita, you made a fool of yourself again. Again, it personalizes the situation.

JFK:

That’s what happens. Well we have been subjected to the last few months, to the charge that we are constantly lowering our, I mean Nixon said it most recently, but it happens every week, that we are appeasing the Soviets. I know he must dismiss all that, but it’s of some importance over here.

CALL TO PRESIDENT HARRY TRUMAN, JULY 26, 1963

On July 26, the day that President Kennedy addressed the nation on national television about the Nuclear Test Ban Treaty, just concluded in principle the day before, this friendly call between two presidents reveals the close camaraderie that Kennedy and Truman now shared in the summer of 1963. Truman felt sufficient closeness to his successor (who had gone to some lengths to cultivate his goodwill, inviting him to the White House for ceremonial occasions) that he offers to support Kennedy with public statements in favor of the test ban.

JFK:

Hello.

TRUMAN:

Mr. President.

JFK:

How are you?

TRUMAN:

Well, I’m all right, and I want to congratulate you on that treaty.

JFK:

Well, I think Averell Harriman did a good job and I think it protects our interests without, but on the other hand, maybe it’s going to help.

TRUMAN:

I do, too, and I’m writing you a personal confidential letter about certain paragraphs in it, which I know you’re familiar with, but I thought that’s what you’d want me to do.

JFK:

Right. Right.

TRUMAN:

But I’m in complete agreement with what it provides. My goodness, maybe we can save a total war with it.

JFK:

Well, I think that’s the whole, I think that’s just to see where we go, and see what happens with China. I think that’s our …

TRUMAN:

Well, and I’m congratulating you on getting that thing done. I think it’s a wonderful thing.

JFK:

Well, I appreciate that very much, Mr. President, that’s very generous and I’m going to make a …

TRUMAN:

I will send a special airmail letter from me, confirming what I’m saying to you now.

JFK:

Good, fine. Well, I think that anything you say about it will be very helpful.

TRUMAN:

Well, I’m not going to say anything publicly until you give me permission to do it.

JFK:

Yeah, well, I think …

TRUMAN:

I don’t like these fellows who quote the President on [unclear] occasions …

JFK:

Well, no, but I tell you what. I’m going to make a speech tonight, then anytime you could say anything would be very helpful.

TRUMAN:

I’ll be glad to do it.

JFK:

Fine.

TRUMAN:

I’m going to St. Louis tomorrow …

JFK:

Yeah.

TRUMAN:

… to the American Legion convention.

JFK:

Yeah.

TRUMAN:

Do you think that’s a good time?

JFK:

I can’t imagine a better.

TRUMAN:

I’ll make some statements on the subject, if it’s satisfactory with you, in connection with the letter which I’m sending you. You’ll get it in the morning.

JFK:

That’d be very helpful.

TRUMAN:

Well, I want to do it the way you want it.

JFK:

Well, fine. Well, if you could say something tomorrow, I think that would really give us a lift.

TRUMAN:

I’ll be glad to say it. I thought maybe, Sunday morning’s papers might be a good place to say it.

JFK:

Oh, good. That’s fine, Mr. President. Well, you sound in good shape.

TRUMAN:

All right. All right. The only trouble with me is that, the main difficulty I have is keeping the wife satisfied. [laughs]

JFK:

[laughs] Well, that’s all right.

TRUMAN:

Well, you know how that is. She’s very much afraid I’m going to hurt myself! Even though I’m not. She’s a tough bird. But I want to do whatever will be helpful to you.

JFK:

Well, that’s fine, I think anything you can say tomorrow would be very good.

TRUMAN:

All right.

JFK:

Thank you very much, Mr. President.

MEETING WITH SCIENTISTS ABOUT NUCLEAR TEST BAN TREATY, JULY 31, 1963

This short but revealing excerpt came from a meeting between President Kennedy and four scientists that took place in the Cabinet Room on July 31, 1963. Kennedy expresses optimism that the Nuclear Test Ban Treaty could lead to a larger détente with the Soviet Union. He also conveys some concern that other nations who are not parties to the treaty (such as China) will conduct their own tests, forcing the United States to respond.

2

JFK:

Well I want to, just want to, say a word or two about this treaty and about how we ought to function under it and what we expect from it and what we don’t expect from it. There are a good many theories as to why the Soviet Union is willing to try this.

I don’t think anybody can say with any precision, but there isn’t any doubt that the dispute with China is certainly a factor, I think their domestic, internal economic problems are a factor. I think that they may feel that [events?] in the world are moving in their direction and over a period of time they … there are enough contradictions in the free world that they would be successful and they don’t want to … they want to avoid a nuclear struggle or that they want to lessen the chances of conflict with us.

[Whatever?] the arguments are, we have felt that we ought to try to, if it does represent a possibility of avoiding the kind of collision that we had last fall in Cuba, which was quite close, and Berlin in 1961, we should seize the chance. We felt that we’ve minimized the risks, our detection system is pretty good, and in addition to doing underground testing, which we will continue, therefore, and we have a withdrawal clause.

And it may be that the Chinese test in the next year, eighteen months, two years, and we would then make the judgment to see if we should go back to testing. As I understood it, we’re not going to test till 1964 anyway, in the atmosphere, so this gives us a year to, at least a year and a half, to explore the possibility of a détente with the Soviet Union—which may not come to anything but which quite possibly could come to something.

Obviously if we could understand the Soviet Union and the Chinese to a degree, it would be in our interest. But I don’t think we, I don’t think that we, knowing all the concern that a good many scientists have felt with the comprehensive test ban, that the detection system is not good enough and that we, which would make our laboratories sterile, it seems to me that we’ve avoided most of that. I know there’s some problem about outer space, maybe some problem about other detection, but I think generally we can keep the laboratories, I would think, growing at a pretty good force, underground testing which we will pursue as scheduled. And we will see what our situation looks like as the Chinese come close to developing a bomb.

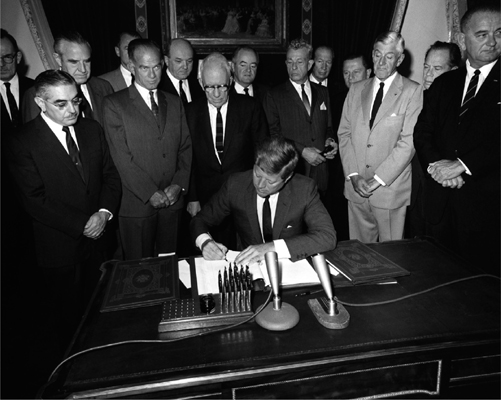

PRESIDENT KENNEDY SIGNS THE LIMITED NUCLEAR TEST BAN TREATY, OCTOBER 7, 1963

In addition, our detection systems will make it possible for us to determine if the Soviet Union has made any particular breakthroughs which result in their deploying anti-missile systems—which we’ve got to expect we can or will do and there’s no evidence that they [have?], which might change the strategic balance, and therefore might cause us to test again. We can prepare Johnston Island

3

so that we can move ahead in a relatively short time. So I don’t think, I’m not sure we’re taking, I think we’re, the risks are well in hand and I would think in the next twelve months, eighteen months, two years a lot of things may happen in the world and we may decide to start to test again, but if we do, at least we made this effort.

That’s the reason, those are the reasons I want to do this. I know Dr. Teller

4

and others are concerned and feel we ought to be going ahead, and [that said?], time may prove that’s the wisest course, but I don’t think in the summer of 1963, given the kind of agreement we’ve got, given the withdrawal features we have, given the underground testing program we’re going to carry out, it seems to me that this is the thing for us to do.