Literary Giants Literary Catholics

LITERARY GIANTS

LITERARY CATHOLICS

JOSEPH PEARCE

LITERARY CATHOLICS

IGNATIUS PRESS SAN FRANCISCO

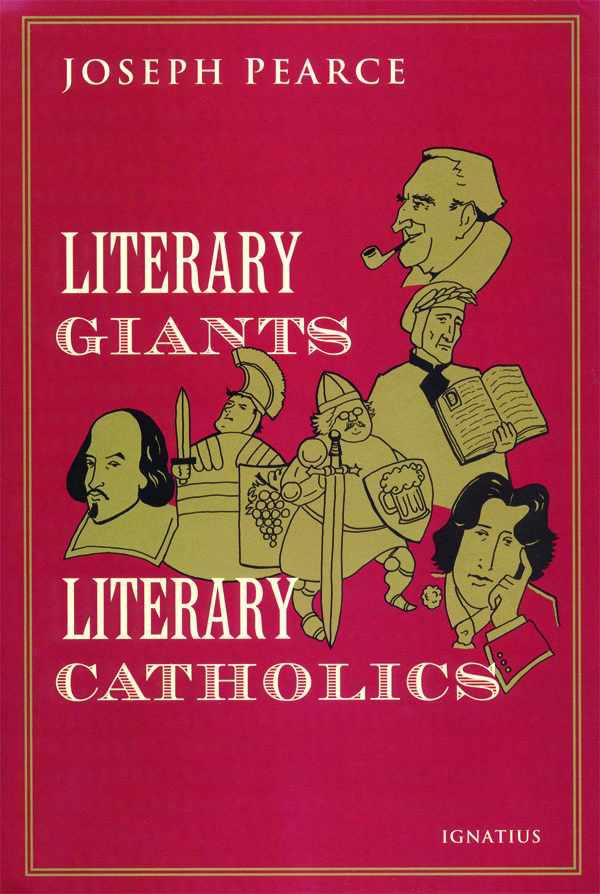

Cover art by John Herreid

Cover design by Roxanne Mei Lum

© 2005 by Ignatius Press, San Francisco

All rights reserved

ISBN 1-58617-077-5

Library of Congress Control Number 2004114951

Printed in the United States of America

To Giovanna Paolina

INTRODUCTION

Converting the Culture: The Evangelizing Power of Beauty

PART ONE: TRADITION AND CONVERSION

1. Tradition and Conversion in Modern English Literature

2. Twentieth-Century England’s Christian Literary Landscape

PART TWO: THE CHESTERBELLOC

3. The Chesterbelloc: Examining the Beauty of the Beast

4. Chesterton and Saint Francis

5. Shades of Gray in the Shadow of Wilde

6. Fighting the Euro from Beyond the Grave: The Ghost of Chesterton Haunts Lord Howe

7. Catholicism and “Democracy”

9. G. K. Chesterton: Champion of Orthodoxy

10. Hilaire Belloc in a Nutshell

12. A Chip off the Old Belloc: Bob Copper In Memoriam

13. Maurice Baring: In the Shadow of the Chesterbelloc

14. R. H. Benson: Unsung Genius

15. Maisie Ward: Concealed with a Kiss

16. John Seymour: Some Novel Common Sense

PART THREE: THE WASTELAND

17. Entrenched Passion: The Poetry of War

18. War Poets: Cutting through the Cant

19. Siegfried Sassoon: Poetic Pilgrimage

20. Emerging from the Wasteland: The Cultural Reaction to the Desert of Modernity

21. Edith Sitwell: Modernity and Tradition

22. Roy Campbell: Bombast and Fire

23. Roy Campbell: Religion and Politics

25. Evelyn Waugh: Ultramodern to Ultramontane

26. Beyond the Facts of Life: Douglas Lane Patey’s Biography of Evelyn Waugh

27. In Pursuit of the Greene-Eyed Monster: The Quest for Graham Greene

28. Cross Purposes: Greene, Undset and Bernanos

PART POUR: J. R. R. TOLKIEN AND THE INKLINGS

31. From the Prancing Pony to the Bird and Baby: Roy “Strider” Campbell and the Inklings

32. J. R. R. Tolkien: Truth and Myth

33. The Individual and Community in Tolkien’s Middle Earth

34. Religion and Politics in

The Lord of the Rings

35. Quest and Passion Play:

J. R. R. Tolkien’s Sanctifying Myth

38. Tolkien and the Catholic Literary Revival

39. True Myth: The Catholicism of

The Lord of the Rings

40. Letting the Catholic Out of the Baggins

41. A Hidden Presence: The Catholic Imagination of J. R. R. Tolkien

42. From War to Mordor: J. R. R. Tolkien and World War I

43. Divine Mercy in

The Lord of the Rings

44. Resurrecting Myth: A Response to Dr. Murphy’s “Response”

45. The Good, the Bad and the Ugly: The Successes and Failures of Tolkien on Film

46. Would Tolkien Have Given Peter Jackson’s Movie the Thumbs-Up?

47. The Forgotten Inkling: A Personal Memoir of Owen Barfield

PART FIVE: MORE THINGS CONSIDERED

48. The Decadent Path to Christ

50. Making Oscar Wild: Unmasking Oscar Wilde’s Opposition to “Pathological” Gay Marriage

51. Truth Is Stranger Than Science Fiction

52. Hollywood and the “Holy War”

53. Three Cheers for Hollywood

54. Purity and Passion: Examining the Sacred Heart of Mel Gibson’s

The Passion of the Christ

55. Paul McCartney: A Grief Observed

56. Above All Shadows Rides the Sun: The Poetry of Praise

60. Shakespeare: Good Will for All Men

61. Modern Art: Friend or Foe?

62. Salvador Dali: From Freud to Faith

63. Mr. Davey versus the Devil: A True Story

64. Totus Tuus: A Tribute to a Truly Holy Father

66. Our Life, Our Sweetness and Our Hope

67. The Presence That Christmas Presents

Most of the chapters in this volume have been published before in a variety of journals on both sides of the Atlantic. My memory is no longer equal to the task of remembering which articles appeared in which journals, but I can, I think, list the names of the journals in which they appeared. These include, in no particular order and with apologies for any sins of omission, the

Catholic Herald

, the

Tablet, Crisis, Gilbert Magazine

, the

Chesterton Review, Lay Witness, This Rock, Christian History, Catholic Social Science Review

, the

Review of Politics, Faith and Reason

, the

National Catholic Register, Catholic World Report

, the

C. S. Lewis Journal, Chronicles

, the

Nicaraguan Academic Journal

, the

American Conservative

, the

Naples Daily News

and

National Review On-Line

. My thanks are proffered to those many individuals who were responsible for commissioning and accepting these articles for the journals listed. I suspect, however, that the list is not complete and apologize, once again, for any lapses in memory.

Many of the chapters in Part V were originally published as articles in the

Saint Austin Review (StAR)

, the Catholic cultural journal of which I am coeditor. The article on Belloc’s

Path to Rome

was originally written for, and published in, the

Encyclopedia of Catholic Literature

, edited by Mary R. Reichardt and published by Greenwood Press in 2004.

Grateful acknowledgements are due, and are wholeheartedly rendered, to Father Joseph Fessio, S.J., for his continuing faith in my work and for his valued advice during the preparation of this volume. Similar gratitude is due to Father Fessio’s colleagues at Ignatius Press, each of whom has worked tirelessly to bring this and my other volumes to fruition.

Final acknowledgement, as ever and always, goes to my ever-patient wife, Susannah, for all the support she gives and is, and to our two children: to Leo, our firstborn, and to little Giovanna Paolina, who rests in the arms of God.

CONVERTING THE CULTURE:

The Evangelizing Power of Beauty

There is a story about an American tourist somewhere in the wilds of rural Ireland. He is hopelessly lost. Desperate for reorientation, he is relieved to see a rustic Irishman, sitting on a fence and sucking a straw. This man has probably lived here all his life, the American thinks to himself; he will surely be able to help. “Excuse me”, he says. “How do I get to Limerick?” The Irishman looks at him for a while and sucks pensively on his straw. “If I were you,” he replies, “I wouldn’t start from here.”

Although one can obviously sympathize with the irate frustration that our lost American must have felt at the unhelpfulness of such a response, there is more than a modicum of wisdom in the Irishman’s reply. Indeed, if the characters are changed, the whole story takes on something of the nature of a parable. Instead of an American tourist, imagine that the hopelessly lost individual is the present writer and that the rustic Irishman is Saint Patrick in disguise. The year is 1978 and I am in the Northern Irish city of Londonderry. I am there because, as an angry seventeen-year-old, I have become involved with the Protestant paramilitaries in Northern Ireland and with a white supremacist organization in England. I am angry. I am bitter. I am bigoted. I hate Catholicism and all that it stands for (although, of course, I have no idea what it really stands for, only what my prejudiced presumption believes that it stands for). Shortly afterward I will join the Orange Order, an anti-Catholic secret society, as a further statement of my Ulster “loyalism” and anti-Catholicism. During this visit to Londonderry, I take part in a day and a night of rioting during which petrol bombs are thrown and shops are looted—all in the name of anti-Catholicism. It is then, at least in the mystical fancy of my imagination, that I meet the rustic Irishman who is really Saint Patrick in disguise. “I am lost”, I say to him (though I am so lost that I don’t even know that I am lost). “How do I find my way Home?” “If I were you,” the saintly Irishman replies, “I wouldn’t start from here.”

Wise words indeed, though at the time they would have fallen on deaf ears. Deaf, dumb and blind, I had a long way to go. The long and winding road that would lead, eventually, eleven years later, to the loving arms of Christ and His Church would be paved with the works of great Catholic apologists such as Newman, Chesterton and Belloc. Newman’s masterful

Apologia

and his equally masterful autobiographical novel,

Loss and Gain

; Chesterton’s

Orthodoxy, The Everlasting Man

and

The Well and the Shallows

; and Belloc’s stridently militant exposition of the “Europe of the Faith”—each of these was a signpost on my path from homelessness to Home. There were, of course, others: Karl Adam’s

The Spirit of Catholicism

, Archbishop Sheehan’s

Apologetics and Catholic Doctrine

and Father Copleston’s

Saint Thomas Aquinas

. I am, therefore, deeply indebted to the great apologists and, in consequence, retain the strongest admiration for those who continue the work of apologetics in our day. I hope and pray that the great work being done by

This Rock

and

Catholic Answers

will bring about a bumper harvest akin to that which was reaped by these great apologists of the past.

Although my own approach to evangelization is somewhat different, I share the same desire to win souls for Christ as do Karl Keating, Tim Ryland and Jerry Usher. I would, in fact, call myself an apologist, albeit an apologist of a different ilk. I would say that I am a

cultural

apologist, one who desires to win converts through the communicating power of culture.

Perhaps a short theological aside will serve as a useful explanation of how cultural apologetics is both different from, and yet akin to, the more conventional field of apologetics. Truth is trinitarian. It consists of the interconnected and mystically unified power of Reason, Love and Beauty. As with the Trinity itself, the three, though truly distinct, are one. Reason, properly understood, is Beauty; Beauty, properly apprehended, is Reason; both are transcended by, and are expressions of, Love. And, of course, Reason, Love and Beauty are enshrined in, and are encapsulated by, the Godhead. Indeed, they have their

raison d’être

and their consummation in the Godhead. Remove Love and Reason from the sphere of aesthetics and you remove Beauty also. You get ugliness instead. Even a cursory glance at most modern “art” will illustrate the negation of Beauty in most of today’s “culture”. Once this theological understanding of the trinitarian nature of Truth is perceived, it follows that the whole science of apologetics can be seen in this light. Most mainstream apologetics can be seen as the apologetics of Reason: the defense of the Faith and the winning of converts through the means of a dialogue with the “rational” and its sundry manifestations. On the other hand, the lives of the saints, such as the witness of Mother Teresa, can be seen as the apologetics of Love: the defense of the Faith and the winning of converts through the living example of a life lived in Love. Finally, the defense of the Faith and the winning of converts through the power of the beautiful can be called cultural apologetics or the apologetics of Beauty.