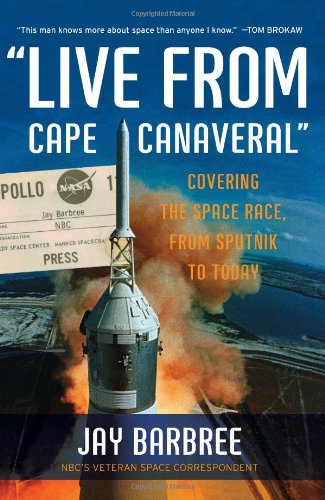

"Live From Cape Canaveral": Covering the Space Race, From Sputnik to Today

Read "Live From Cape Canaveral": Covering the Space Race, From Sputnik to Today Online

Authors: Jay Barbree

Tags: #State & Local, #Technology & Engineering, #20th Century, #21st Century, #General, #United States, #Military, #Aeronautics & Astronautics, #History

Covering the Space Ra

ce, from Sputnik to T

oday

(

Jo Barbree

)

CANAVERAL”

Jay Barbree

This book is for…

The damnedest aviati

on and space writer I’ve ever seen…

MARTIN CAIDIN

SEPTEMBER

14, 1927—

MARCH

24, 1997

(Caidin Collection)

Jay Barbree was present at the creation of the space age. As he likes to tell it, he was on a date in his home state of Georgia the night the Russian satellite

Sputnik 1

passed over the United States.

I don’t know what happened to his date, but I do know Jay decided at that moment to make the space age his life’s work. He moved to Cape Canaveral, Florida, and began a lifelong love affair with the space program, quickly developing a reputation as the reporter who knew the personalities, the technology, the politics, the triumphs, and the tragedies of this daring enterprise better than any other.

Now, fifty years after

Sputnik 1

, Barbree gives us a vivid, first-hand account of how the race into space changed the world. It is a monumentally important story, and no one is better equipped to tell it from the ground up.

Barbree is the only reporter to have covered every mission flown by astronauts. He was there the day

Apollo 1

burned, the day

Challenger

exploded shortly after takeoff, the day

Columbia

broke up in the skies over Texas.

In his own way, Jay Barbree has been to the moon and back, the space station and back. He’s also been on the verge of death and brought back to life. Training for the Journalist in Space Project, Jay suffered

“sudden death” while jogging on the sands of Cocoa Beach. He made a heroic recovery and returned to what he loved best: reporting on the space program.

Live from Cape Canaveral

is his up-close and personal account of a half-century of space exploration. It tells the stories of the courage and genius of the pioneers. But it also describes the mistakes, the feuds, the wild times, and the indelible impression left by these men and women who allowed us to escape the bonds of Earth and fly into the unknown.

A thousand years from

now, historians will mark this time as the beginning of the greatest age of exploration ever. Jay Barbree takes you on that first giant step for mankind.

T

OM

B

ROKAW

August 24, 2006

I

n 1957, Cape Canaveral was the most vital and most intensely exciting place in the country. It offered cutting-edge technology in a time of nineteen-cent-a-gallon gasoline, nickel Cokes, two-bit drive-in movies, and the hit of the television season

Leave It To Beaver

. It was a time when doors went unlocked, when virgins married, when divorce ruined your social standing, and when folks spent their lives working for the same company with the promise of lifelong retirement checks.

In 1957 few that walked this planet reflected on the fact they were actually inhabitants of a mortal spaceship eight thousand miles in diameter, circling one of the universe’s 10,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 (ten to the twenty-fourth) stars at 67,062 miles per hour.

However, two groups of men and women—given the era, it was mostly men—were actually consumed, day and night, by the realities that we were all astronauts living on spaceship Earth. One group worked in the United States at Alabama’s Redstone arsenal; the other busied itself in a Soviet hamlet called Baikonur on the steppes of Kazakhstan.

Like the American group, the Russians developed and worked on machines to lift nuclear warheads and stuff off our planet, and on the evening of October 4, 1957, one of their creations, a large white rocket

called R–7, was being fueled for what some would call the single most important event of the twentieth century. Nearby, inside a steel-lined concrete bunker, an intense middle-aged man named Sergei Korolev was at work. His job, as the chief rocket engineer for the USSR, was to orchestrate the stop-and-go countdown. But unlike his American counterpart, Wernher von Braun, Korolev had the full blessing and support of his country’s communist government.

Cape Canaveral. In the 1950s and 1960s, dozens of rockets and missiles were launched from this

real

Disney World.

(NASA).

While Korolev had been chasing the goal of space flight at breakneck speed, Dr. von Braun had been pleading with President Dwight David Eisenhower to let him launch an Earth satellite. Only the year before, von Braun had moved his rocket and satellite to its launch pad without permission. He was going to launch it anyway, pretending that the satellite accidentally went into orbit. But Lieutenant Colonel Asa Gibbs, Cape Canaveral’s commander, ordered th

e satellite launcher returned to its hangar. Colonel Gibbs cared more about his ass and making full colonel than he did history.

Now, with von Braun’s rocket in storage, Sergei Korolev’s R–7 was fueled, and his launch team was ready to send a satellite into orbit and send Russia into the history books.

“Gotovnosty dyesyat minut.”

Ten minutes.

Steel braces that held the rocket in place were folded down, and the last power cables between Earth and the rocket fell away.

“Tri…

“Dva…

“Odin…”

“Zashiganive!”

IGNITION!

Flame created a monstrous sea of fire. It ripped into steel and concrete and blew away the night. It sent orange daylight rolling across the steppes of Kazakhstan, quickly followed by a thunderous train of sound that shook all that stood within its path.

Sputnik,

Earth’s first artificial satellite, was sent into orbit on October 4, 1957.

(NASA).

R–7 climbed from its self-created daylight on legs of flaming thrust and soon appeared as if it were an elongated star racing across a black sky. It fled from view and left darkness to once again swallow its launch pad as it became just another distant star over the Aral Sea.

While others strained to see the final flicker of the rocket, Korolev was interested only in the readouts. He sat transfixed by the tracking information streaming into the control room. The data were perfect. He was intently interested in each engine’s shutdown. Separation of each stage had to be clean. And when the world’s first man-made satellite slipped into Earth orbit, he permitted himself to rejoice with the others.

It would be called

Sputnik

(fellow traveler), and ninety-six minutes later, it completed its first trip around our planet, streaking over its still-steaming launch pad, broadcasting a lusty

beep-beep-beep

.

A dream had been realized.

Wild celebrations exploded across the Soviet Union.

I

n the NBC newsroom in New York, editor Bill Fitzgerald had just finished writing his next scheduled newscast when the wire-service machines began clanging. The persistent noise rattled most everything. Fitzgerald ran to the main Associated Press wire and began reading.

BULLETIN

London, October 4

th

(AP)

Moscow radio said tonight that the Soviet Union has launched an Earth satellite.

The satellite, silver in color, weighs 184 pounds and is reported to be the size of a basketball.

Moscow radio said it is circling the globe every 96 minutes, reaching as far out as 569 miles as it zips along at more than 17,000 miles per hour.

Fitzgerald froze. He didn’t want to believe his fully written newscast had just been flushed down the toilet.

“Damn!” he cursed in protest before hurrying across the newsroom and bursting into Morgan Beatty’s office. “Mo, we’ve gotta update,” he shouted. “One of the damn Russian missiles got away from them, and they lost a basketball or something in space.”

Beatty, a World War II correspondent, never came unglued in battles and he wasn’t about to be upset by an agitated editor. “Give me that,” he demanded, snatching the wire copy from Fitzgerald’s hand.

Beatty’s eyes widened as he read. “Jesus Christ, Bill, you know what this is? The Russians have put a satellite in Earth orbit! They’ve been talking about it, and damn it, they’ve really done it!”

Fitzgerald took a deep breath. “Okay, what do we do, Mo?”

The veteran newscaster didn’t hesitate. “We’ve got to get this on the air, now!”

S

putnik

came around the world, streaking northeast over the Gulf of Mexico and Alabama. Its current orbit took it south of Huntsville, where the U.S. Army’s rocket team at the Redstone Arsenal was enjoying dinner and cocktails with some high-powered brass from Washington. One of the guests was Neil H. McElroy, who was soon to be the secretary of defense. Wernher von Braun was delighted. He judged McElroy as a man of action and when he replaced the current defense secretary, Charles E. Wilson, action would be what the army’s rocket team would get. Dr. von Braun and his crew had

been trying to punch a satellite into Earth orbit for months, but Wilson and President Eisenhower thought it was just so much nonsense and von Braun and his team had been left outside with their dreams.

But von Braun was as much a charmer as he was a genius in rocketry. He was tall, blond, and square-jawed, and that evening he had come with charts and slides and reams of data to brief McElroy on the potential of the army’s rockets to bring American space flight to reality. McElroy listened with interest and understanding. Dr. von Braun was jubilant; he felt he was getting through. He was not aware

Sputnik

was about to wreck his carefully planned sales job.

“Dr. von Braun!”

Von Braun sprung about, to see his public affairs director running into the room.

“They’ve done it!” shouted Gordon Harris.

“They’ve done what?”

“The Russians…” Harris ran up to join the group. “They just announced over the radio that they have successfully put up a satellite!”

“What radio?” demanded von Braun.

“NBC.” Harris sucked in air. “NBC was just on with a bulletin from Moscow radio. They’ve got the sounds from the satellite. The BBC has also—”

“What sounds?” von Braun interrupted.

“Beeps,” Harris told him. “Just beeps. That’s all. Beeps.”

Von Braun turned and stared at McElroy. “We knew they were going to do it,” he said with disgust. “They kept telling us, and we knew it, and I’ll tell you something else, Mr. Secretary.” A tremor of suppressed fury wrapped his words. “You know we’re counting on

Vanguard

. The president counts on

Vanguard

. I’m telling you right now

Vanguard

is months away from making it.”

A panel of scientists had recommended the development of a new rocket called

Vanguard

, arguing that a booster with nonmilitary applications, even though it was a product of the navy, would lend more dignity to a scientific project. Eisenhower went with it, ignoring the fact von Braun’s army team was the only group in America with the experience and ability to launch a satellite, and McElroy gestured in protest. “Doctor, I’m not yet the new Secretary. I don’t have the authority to—”

“But you will,” von Braun broke in, his words raw with emotion. “You will be, and when you have the authority,” he said sternly, “for God’s sake turn us loose!”

T

he night of

Sputnik

, I was working for WALB radio and television in Albany, Georgia, where I was more interested in a Marilyn Monroe look-alike named Ann Summerford than in the world’s first artificial

satellite. My best friend and coworker, Gene McCall, was dating Ann’s sister, Leslie, and neither of us had the slightest hint what role

Sputnik

would play in our lives.

Gene, who would grow up to be a Princeton physicist and work on nuclear weapons as a senior scientist for the Los Alamos National Laboratory before becoming chief scientist of the Air Force Space Command, figured out

Sputnik

’s high five-hundred-mile-plus orbit would keep it and its trailing booster rocket lit by the sun as they passed over a dark Georgia. Theoretically, if we focused on the southwest sky at the precise moment, we just might see the tumbling booster. Of course the basketball-size

Sputnik

was too small to see, but we decided to take our chances with the booster, and we d

rove to a dark spot out of town and waited.

Minutes passed and as Gene had calculated, we saw a star moving. It raced over our heads and disappeared below the star-filled horizon. Its flight path appeared to change as it moved across the sky. But it didn’t. It was Earth that moved. Like

Sputnik

itself, the booster rocket was in its own independent orbit, moving around the planet every ninety-six minutes on a firm track fixed by gravity. Earth was rotating beneath it at the rate of about eight hundred miles each hour at Albany’s latitude. We knew we were seeing the future.

I did a report on

Sputnik

and began to imagine ways I might move to Cape Canaveral and cover the impending space race. I had no idea then that I would spend more than fifty years covering every space flight by astronauts and amassing the most detailed files of known and unknown facts of space history. I built sources and contacts not only in America but in Russia as well, and in the autumn of my career I would write this book—my lifetime’s most important story. Besides, I had had a run-in with Albany’s Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, which made relocating seem even more attractive. I wouldn’

t say I was run out of town but I sure as hell was out in front, leading the parade.

O

nly a month after

Sputnik 1

, the Russians did it again.

Sputnik 2

weighed 1,120 pounds, and it soared more than a thousand miles

above Earth. The numbers were unbelievable to an American public struggling to understand what was going on. Where were our rockets? Where were our satellites? And what the hell was inside this thing? A dog?