Living in Threes (22 page)

Authors: Judith Tarr

Tags: #Science Fiction & Fantasy, #Teen & Young Adult, #Fantasy, #Science Fiction, #Coming of Age, #Aliens, #Time Travel

The trail of the scarab led to the port city across from the island on which Jian had been born. She knew which ancient culture the bead had come from and roughly how old it was, but she still had no idea what it meant. There seemed to be no connection at all between a scarab from Egypt’s Old Kingdom and an interstellar viral plague.

The person who had the original was a collector whom she had met before, an Earthling who traveled often offworld but kept a shop in the old city where he sold the occasional artifact. Not everything he dealt in was legal, but he had a good reputation. He was trustworthy, if not always careful to stay within the limits of a complex and sometimes contradictory code of law.

He had been away on one of his collecting expeditions, her sources told her, but had come back just a few days before. She took precautions: she made sure no one was following her either physically or on the web; she determined that all of the spybots around his shop were maintained or cleared by the collector himself. Finally she sent a message requesting entry, and received an answer keyed to her specific code:

Come

.

It seemed she was expected. Even so, she did not rush in all at once. She approached slowly, in clear view of the bots.

The shop’s door opened as she came to it. She paused to run a scan. No weapons were trained on her. It was all open and honest as far as she could see.

She stepped inside.

The shop was deliberately, almost ostentatiously old-fashioned, in a style that was frankly ancient: dim, dark, cluttered. Instead of clean surfaces and virtual images that one selected from a range of menus, it was full of the actual artifacts.

Nothing there was particularly rare or valuable, but some of it was interesting. If Jian had had time, she would have loved to spend a few hours rummaging in the shelves and cabinets.

She could not spare those hours. She had seen a man sitting on a doorstep in a posture she recognized from too many worlds less blessed than Earth. He was sick. He was not one of the outcast, either—one of those who had been cut off, willingly or not, from the web. He was fully and properly protected, and the virus had taken all the strength out of his body.

She had the latest defenses, double-armored and fully charged. She would order them for Meru as soon as she finished here.

The collector was not in the shop, but he had left a message, a trail for her to follow. It led her to the back and up a stair to room as deliberately antique as the shop.

He was there, and he was dead. He had died quickly: he was sitting up with no sign of trauma, except for the blood trickling from his mouth and nostrils, ears and eyes.

The packet lay on the table beside him. Jian had come prepared: she carried a decontamination module. It flashed over the packet and signaled that it contained no threat.

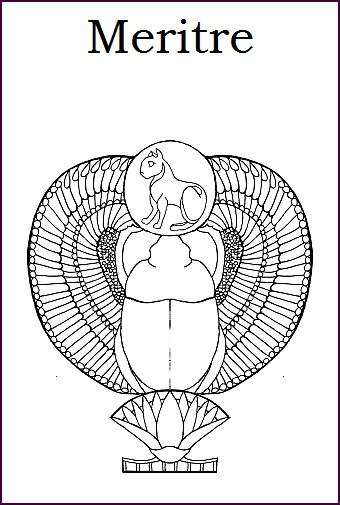

Inside the packet was exactly what the data bead had promised: a scarab cupped in the mummy of a lotus blossom, resting on a scrap of papyrus that, from its shape, must once have been a wrapping for the rest. A stasis field prevented the fragile organic material from puffing to dust.

She ran the scan again, but this time she set it to detect and trace any viral contaminant. The search took so long that she had begun to sag in disappointment, sure that it had found nothing, when the scanner flashed.

The sample held nothing that the scanner considered dangerous, but there were slight anomalies. Those anomalies were little enough in themselves, but they hinted at something more.

It was maddening, because the traces were so faint, and yet there was no denying that they were there.

The collector had left a message for her on the shop’s web. “I found this in a cache of artifacts on Alpha, last opened in the early years of the Lost Colony. I kept it because of your interest in that particular history. It seems a trivial thing to be so carefully preserved. Perhaps there is more to it than there seems to be.”

Jian weighed the scarab in her hand. Trivial indeed.

And yet—it came from the Lost Colony. The first great plague of Earth’s foray into space had destroyed every human being on that world.

This bead and this shadow of a flower had been there; had survived the plague and the cleansing that followed, the storm of fire that swept the planet down to the bare rock. To someone, for some reason she did not yet understand, this small thing had been immensely valuable.

Jian closed her eyes and sighed. She had been hoping to spend the night at home with her family—her daughter, her brother, all the aunts and uncles and cousins. But the hour was late and a storm was brewing, and suddenly she was tired. She had come a long way in search of an answer, only to find more questions.

Maybe there was no answer. Maybe it was all a preposterous prank, a joke played on her by one of her rivals, or a colleague with a twisted sense of humor.

She would know more tomorrow. And she would see Meru, which made her happy in spite of everything.

She took a room in a hostel nearby. By then her head ached dully; she was more than ready to sleep.

When she woke, she was dying. The being called Grey sat beside her.

She knew he was not real, because she could see through him. Her fever had conjured him up; the sickness gave him words to speak.

“Well done,” he said. “Now wait. The rest will unfold as it must.”

Waiting was one of the few things she could do at the moment, but she would be done with that all too soon. She would have told him so, if he had stayed.

Since he did not, she decontaminated the scarab and the flower yet again, even more carefully than before, and wrapped and sealed them and keyed the packet to Meru. She left it where she knew someone from Consensus would find it.

She hoped it would be Vekaa. He was as close to a disease specialist as Earth still had.

When that was done, she set her implants to record her memories of Grey and of the scarab, and to finish the recording here, soon, as the life left her body.

She had done all she could. Probably she had done more than she should.

She appreciated the irony. The plague she had hunted for so long had caught her at last, just as she came within reach of proving her theory. If there were still gods anywhere in the universe, they must be amused.

Jian’s mind was breaking up; her streams of data were running dry. She tried to reach Meru, to tell her—something; anything. But her grip on the world had let go.

The data stream broke apart as Jian’s mind had done, disintegrating into fragments of random information. It was dead, gone, erased, everywhere on the web. But it was burned into Meru’s memory.

Meru lay in the light of a million suns, with tears running down her face.

Yoshi’s head blocked a fraction of the light. She could not make out his expression: the stars were too bright. But his voice was, as usual, worried. “Are you all right? What happened?”

“I have got to stop doing things that make you ask that,” she said.

“That would be good,” he said. “But since you’ve done it again, will you please tell me what’s wrong this time?”

Meru could not decide whether to laugh or sob. The sound that came out could have passed for either or both. “I found what I needed to find. What my mother did. Why she—why she died.” She stopped, breathed, made herself go on steadily. “There’s one last thing I have to do. Since there’s no way I’m going to be able to talk you out of coming with me, will you just come? And not argue?”

He dropped down from above her, so that finally she could see his face. It was tired and drawn and amazingly, incongruously happy. She could hardly help herself: she touched it, as if to assure herself that it was real.

It was. He was. “When are we going?” he asked.

He was as crazy as Meru.

As he would be. He wanted to be a starpilot, too.

Chapter 21

Meritre felt strange. The spirits that had been inside her were gone, cut off by Meredith’s will. What she felt, she realized as she watched the sun come up over the city, was loneliness. She was alone inside herself, as every human thing was supposed to be—and it felt deeply and painfully wrong.

She was not angry at Meredith. People did what they did; and Meredith had had a terrible shock. But Meritre did wish her other self had chosen a better time. Meru’s people needed knowledge that Meritre had, or could get. Now there was no way to pass that knowledge to her.

Meritre could surrender and fall back into her old, ordinary life. Or she could do something. It might not be of any use, but at least she would have tried.

Her blue bead, her simple and unremarkable scarab, seemed to be the key to the spell that bound them all. Meredith had said that her people had found it somewhere Meritre was unlikely ever to go: in a passage below the princess’ temple.

Meritre would go to the temple. The gods might speak to her if she did that, or she might see where the tomb was. She might even find a way to tell Meru without Meredith to carry the words onward.

It was worth doing. Certainly it was better than fretting uselessly at home.

Her father was to work in the temple today. He had to finish carving and painting the statue there before it was put in place in the tomb.

She was not foolish enough to ask him where the tomb was hidden. He would not answer; he was sworn to silence. But she knew a way.

She managed to distract him enough with fuss and chatter that when he left the house, he forgot the basket of bread and beer that should have been his morning meal. Someone had to take it to him or he would be hungry all day.

Meritre had made sure she had to be that someone. Her brothers were busy in the king’s workshop. Aweret was feeling the weight of the baby and needed to rest.

By the time Meritre reached the river, the ferry was nearly full. That was almost enough to convince her that the gods did not approve of her plan. But her father needed to eat, and Meru’s world needed much more than that. She balanced the basket on her head and squeezed in among the crowd.

Most of them were mourners going to visit their relatives among the tombs. They were a big family, not wealthy enough to own their own ferry, but much sleeker and better dressed than Meritre.

Some of the younger men eyed her with clear intention. She kept her own eyes bent downward.

When one of the men moved toward her, she measured paths of escape. There were not many, and most of those were also occupied by well-fed young men.

A clear voice rang above the murmur of conversation. “Khafre! Come here and hold my sunshade.”

The man with the wandering feet stopped short. Meritre had to crane a bit to see through the thicket of bodies, but after a moment she saw who had spoken: a woman who must be Khafre’s mother or aunt, seated on a chair that must have been brought for just that purpose. She looked as high and haughty as one might expect, noblewoman that she clearly was.

But as her eye caught Meritre’s, there was something else in it. A surprising warmth; a flicker of sympathy.

She reminded Meritre of the king, a little. Meritre bowed to her, slightly but visibly.

And she bowed back. That left Meritre feeling somewhat off balance, but somehow, out of nowhere in particular, rather ridiculously happy.