Living Low Carb (10 page)

Authors: Jonny Bowden

The checking-account model, known as the

energy-balance theory

, has been the dominant theory of weight loss for years. The entire low-fat movement has been built on it: take in fewer calories and burn more, and you will lose weight. You have probably been hearing this advice for years. While this view is not entirely without merit, it’s so far from the whole picture as to almost constitute dietary malpractice.

The thinking behind low-carbing belongs to the second category of theories about weight loss, the Telephone Theory. This view asks a critical question: what goes on inside the body once those calories are taken in? Why do some people store everything as fat and others don’t? What determines whether what you eat goes on your hips or is burned up as energy and disappears as heat into the atmosphere?

The answer is one word:

hormones

.

Hormones control just about every metabolic event that goes on in your body, and you control hormones via your lifestyle. Food—along with several key lifestyle factors such as stress—is the drug that stimulates hormones, and those hormones direct the body to store or burn fat, just as they direct the body to perform a gazillion other metabolic operations. (Dr. Barry Sears has said that “food may be the most powerful drug you will ever encounter[,] because it causes dramatic changes in your hormones that are hundreds of times more powerful than any pharmaceutical.”) Hormones are the air-traffic controllers determining the fate of whatever flies in.

If your food is stimulating the wrong hormones or creating a hormonally unbalanced state, you will find it extremely difficult, if not impossible, to lose weight and keep it off.

In this chapter, you will learn why it is so vitally important to balance your hormones if you want to lose weight. It is probably as important as—or more important than—counting calories, and it is

certainly

more important than reducing dietary fat. But managing our hormones has even bigger consequences. Insulin—the hormone most targeted by the low-carb diet plans discussed in this book—is at the hub of a significant number of diseases of civilization. When you control insulin, you hugely increase the odds that you will be able to control your weight. But, as you will see, you

also

reduce the risks for heart disease, hypertension, diabetes, polycystic ovary syndrome, inflammatory diseases, and even, possibly, cancer.

So let’s get to know the players in our hormonal dance. If I’ve done my job, at the end of this chapter you’ll have a much better understanding of what has now come to be popularly known as “Endocrinology 101”: how the body

makes

fat,

stores

fat, and, finally,

says good-bye to

fat. You’ll also understand why the same eating plan that helps you lose weight

also

has the positive “side effect” of preventing you from becoming a medical statistic.

T

HE

S

TAR OF THE

S

HOW

:

E

XPERTS

W

EIGH

I

N

O

N

I

NSULIN

“Insulin is the key to the vast majority of chronic illness.”

—Joe Mercola, DO

“There is an epidemic of insulin resistance in the world at large.”

—Gerald Reaven, MD

“When you have excess levels of insulin, it’s like a loose cannon on the deck of a hormonal ship.”

—Barry Sears, PhD

“Insulin sensitivity is going to determine, for the most part, how long you are going to live and how healthy you are going to be. It determines the rate of aging more so than anything else we know right now.”

—Ron Rosedale, MD

The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly: Insulin and Its Discontents

Insulin, a hormone first discovered in 1921, is the star actor in our little hormonal play. It is an anabolic hormone, which means it is responsible for building things up—putting compounds (like glucose and amino acids) inside storage units (like cells). Its sister hormone, glucagon, is responsible for breaking things down—opening those storage units and releasing their contents as needed. Insulin is responsible for

saving

; glucagon is responsible for

spending

. Together, their main job is to maintain blood sugar within the tightly regulated range it needs to be in, to keep your metabolic machinery running smoothly.

And to keep you from dying. Without insulin, blood sugar would skyrocket and the result would be metabolic acidosis, coma, and death, the fate of virtually every type 1 diabetic in the early part of the twentieth century prior to the discovery of insulin. On the other hand, without glucagon, blood sugar would plummet and the result would be brain dysfunction, coma, and death. So the body knows what it’s doing. This little dance between the forces that keep blood sugar from soaring too high and those that prevent it from going too low is essential for survival. It’s interesting to note that while insulin is the only hormone responsible for preventing blood sugar from rising too high, there are several other hormones besides glucagon—cortisol, adrenaline, noradrenaline, and human growth hormone—that prevent it from going too low. Insulin is such a powerful hormone that five other hormones counterbalance its effects.

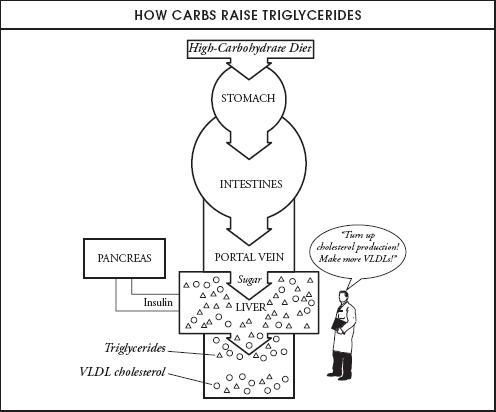

How a High-Carbohydrate Diet Raises Both Cholesterol and Triglycerides

Let’s follow the nutrients you eat on their journey through the body. When you eat food—any food—it mixes with acids and enzymes from the stomach, pancreas, and liver that break it down into smaller molecules. The nutrients are then absorbed through the intestinal walls, while the indigestible parts of the food pass through the digestive system as waste. Proteins break down into amino acids, carbohydrates into glucose, and fats into fatty acids. These pass through the intestinal walls into the portal vein, which is like their private passageway into the liver, the central processing plant of the body. After the liver works its magic, often repackaging these compounds into different forms, the new forms are released into the general circulation of the bloodstream, where they are transported to cells and tissues to be either used or saved for a rainy day.

As these smaller units pass through the portal vein en route to the liver, the pancreas immediately takes notice of the parade and responds by secreting our star player, insulin. It secretes

some

insulin in response to protein; but when it sees carbohydrates in the passageway, its eyes light up, and it brings out the big guns and goes to town. (Fat doesn’t even rate a “hello” from the pancreas and has no impact on insulin.)

Under the influence of this incoming insulin, the liver does a number of things. First, it decides how much of the sugar coming in is excess. It makes that decision based largely on how much insulin the pancreas has decided to send along to accompany the payload. If there’s a lot of insulin, the liver says,

“Woo hoo, we’ve got a truckload of sugar on our hands; let’s get busy.”

Some of the incoming sugar will pass right through (as glucose) to the bloodstream to be transported to muscle cells—which can use a hit of sugar now and then for energy—and to the brain, which needs sugar (or ketones, which we’ll discuss in detail later) to think and do all the other good things that brains like to do. Part of the excess sugar will be converted to the storage form of glucose, called glycogen, much of which will stay right there in the liver. (Glycogen is also stored in the muscles, but muscle glycogen is like a private bank account that can be used only by the muscle in which it is stored.) The liver doesn’t hold a lot of glycogen, so if there is still excess sugar, which there almost always is after a high-carbohydrate meal, it is packaged into triglycerides (fats found in the blood and in the tissues). The high level of insulin accompanying the high-carbohydrate meal stimulates the cholesterol-making machinery: the body starts churning out more cholesterol, which it then packages (together with triglycerides) into little containers called VLDLs (very low-density lipoproteins), most of which eventually become LDLs (low-density lipoproteins), or “bad” cholesterol. This is how a high-carbohydrate diet raises both triglycerides and cholesterol.

Which Is Worse, Sugar or Fat? No Contest!

Why, you may ask, does the liver feel this compelling need to get rid of the excess sugar, anyway? Why doesn’t it just give it a pass and let it go into the bloodstream as is? Why create all this work for itself? Why bother to turn it into triglycerides in the first place?

That’s a very good question, and the answer is central to understanding the health effects of a lower-carbohydrate diet:

sugar is far more damaging to the body than fat

. In a very real sense, what the liver is doing is

detoxifying

sugar into triglycerides.

As you just read, eating high-carb foods usually makes your cholesterol go up. Here’s why: insulin turbocharges the activity of a particular enzyme—with the unwieldy name of HMG-coenzyme A reductase, or HMG-CoA reductase—that runs the cholesterol-making machinery in the body. (Glucagon inhibits the HMG-CoA reductase enzyme, so your body makes less cholesterol.) So high levels of insulin basically signal the liver to ramp up the production lines on cholesterol, and high levels of sugar signal it to ramp up the production of triglycerides. (Interestingly enough, if you ate a diet of almost 90% fat, your cholesterol numbers would probably drop, because there would not be enough insulin around to power the cholesterol-making machinery.) However, the American diet—high-fat

and

high-carbohydrate—virtually guarantees both high cholesterol and high triglycerides. Your Honor, the body had

motive, means, and opportunity

. Motive—to get rid of the excess sugar. Means—fat and sugar. Opportunity—tons of insulin to drive the works. Case closed: when there’s plenty of excess sugar and insulin around, triglycerides skyrocket, and so does cholesterol.

At this point, it may start to occur to you that since sugar is made into triglycerides, then maybe one of the reasons blood levels of triglycerides are lowered on a low-carb diet is because there’s less excess sugar coming in to require packaging into triglycerides in the first place. And you’d be absolutely, 100% right. (Cholesterol usually comes down as well, but as you’ll see later, that doesn’t matter nearly as much.) This lowering of triglycerides is one of the major health benefits of a low-carb diet—high triglycerides are far more of a danger sign for heart disease than high cholesterol ever was.

You may also be thinking that the higher levels of fat that are frequently (though not always) part of low-carb diet plans may not be so bad after all, if they’re not accompanied by the high insulin levels that go with high-carb diets. You’d be right on that count as well.

Insulin Prevents Fat Loss

An important thing to remember just from a weight-loss point of view is that insulin isn’t only responsible for getting sugar into the cells and out of the bloodstream: it’s also responsible for getting

fat

into the fat cells

and keeping it there

. Insulin actually prevents fat burning. That’s why a low-carb diet usually produces more weight loss than a high-carb, low-fat diet with the same calorie count. By lowering insulin, you open the doors of the fat cells and allow the body to release fat.

One of the ways insulin interferes with fat burning is by inhibiting carnitine, an amino acid–like compound in the body that is responsible for escorting fatty acids into the little central processing units of the muscle cells, where those fats can be burned for energy. By inhibiting carnitine, insulin inhibits fat-burning. That’s one reason you shouldn’t eat a big meal before going to bed—the resulting high levels of insulin virtually ensure that your body will not be breaking down fat as you sleep, but instead will be busy storing whatever is around in the bloodstream. (A side note: many years ago, an American health magazine decided to do a weight-loss story on sumo wrestlers. The writers reasoned that the wrestlers knew everything there was to know about putting on weight, so if we could just learn what it was they did, we’d know what

not

to do if we wanted to slim down. One of the major rituals of the sumo wrestlers was eating a huge meal and then going right to bed.)

So on a high-carbohydrate diet, you’ve got all this sugar coming into your system—because all carbs eventually break down into sugar—and your liver can basically do one of three things with it: