Living Silence in Burma (33 page)

Read Living Silence in Burma Online

Authors: Christina Fink

Similarly, since the commencement of military rule in 1962, no clear mechanism has been established for determining the top general’s successor. As a result, ambitious generals have jockeyed for the highest position. Lower-ranking officers have sought to improve their own fortunes by allying themselves with powerful military patrons, but they also run the risk of being punished if their patron falls. Some officers seek to maintain a more neutral stance or cultivate relations with all the leading generals in order to protect themselves.

The personalization of power and the lack of well-defined systems for decision-making have other consequences as well. Many officers are afraid to make any decisions by themselves for fear their decision will displease a higher-ranking officer. As a result, they pass even small matters up to a higher level or ignore the problem and hope it will disappear by itself. This creates great inefficiencies in governance and reinforces feelings of indispensability among those top generals who do dare to make decisions.

Those in power continue to enjoy an opulent lifestyle and public demonstrations of respect, whether heartfelt or not. Although it seems clear that there is plenty of disaffection within the military, such feelings will not easily translate into insurrection. Officers and soldiers doubt their ability to succeed at such an effort and fear severe punishment. Others worry that if there were political reform, they would face retribution for the abuses they committed in the past. As a result, military rule continues, even though those with the guns are not all in favour of it.

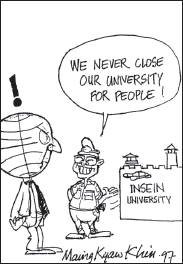

9 | Prison: ‘life university’

Many people in Burma avoid politics because of their well-founded fear of being tortured and sent to prison. Torture is carried out both to extract information and to destroy the morale of activists, and includes intense physical pain, intimidation and humiliation. Conditions in Burmese prisons are extremely difficult, with insufficient food, medicine and bathing water frequently leading to debilitating health conditions and the premature deaths of many. Prison sentences can range anywhere from a few years to one hundred years, and prisoners can continue to be held even after they have completed their sentences.

Still, prison is a place where people have a chance to think and analyse issues deeply and intimate bonds are formed. While the entire country, and even the military itself, has been compared to a prison, for some, experiences in Burma’s actual prison system can be mentally liberating. Despite the miserable living conditions, in some prisons activists endeavour to find ways to engage in political debates and to learn from each other. This chapter explores how political prisoners try to create a community, maintain their morale and improve themselves, and looks at what happens to them after they are released.

Arrest and sentencing

Political activists are usually arrested without a warrant in the middle of the night and taken away with a hood over their heads. Before they are charged in court, they are tortured to extract information and to punish

them. As one intelligence officer told an activist, ‘You will be squeezed to the last drop like sugar cane in a juice press.’ This is usually the most terrifying period for a political prisoner and can last from a few days to a few months.

1

Until late 2004, interrogation and torture during the detention period were carried out by military intelligence agents generally at interrogation centres. Since then, the newly established Military Affairs Security or the Special Branch of the police have carried out this function.

The Human Rights Yearbook

for 1997/98, compiled by the Human Rights Documentation Unit of the exiled National Coalition Government of the Union of Burma, describes the techniques used in interrogation centres as including:

beatings rigorous enough to cause permanent injury; shackling of the legs or arms; burning victims with cigarettes; applying electric shocks to the victims’ genitals, finger tips, toes, ear lobes, and elsewhere; suffocation; stabbing; rubbing of salt and chemicals in open wounds; forcing victims to stand in unusual and uncomfortable positions for extended periods of time, including ‘riding the motorcycle,’ which entails standing with arms outstretched and legs bent, and the ‘helicopter,’ in which the victim is suspended by the wrists or feet from a ceiling fixture and then spun around; deprivation of light and sleep; denial of medicine, food, exercise, and water for washing; employing the ‘iron rod’ in which iron or bamboo rods are rolled up and down the shins until the skin is lacerated; ordering solitary confinement with extremely small and unsanitary cells for prolonged periods, and using psychological torture including threats of death and rape.

2

During this period, family members are not informed where their loved one is being held, increasing the mental stress for both the person detained and his or her family.

After the interrogation period is over, activists are charged. Trials are often perfunctory affairs, sometimes lasting less than fifteen minutes.

3

Many defendants are not allowed to have a lawyer represent them or must accept a lawyer appointed by the authorities.

4

The accused generally cannot produce their own witnesses or speak in their own defence. Many trials are held in a closed court at Insein Prison, with the judge simply reading out the sentence from a piece of paper.

Since the mid-1990s, sentences for political activists accused of even the most trivial offences have typically ranged from seven to fifteen years. On 7 June 1996, the military regime announced Decree 5/96, ‘The

Protection of the Stable, Peaceful, and Systematic Transfer of State Responsibility and the Successful Implementation of National Convention Tasks, Free from Disruption and Opposition’. According to this decree, anyone caught publicly airing views or issuing statements critical of the regime can be sentenced to up to twenty years in prison.

5

NLD members have been sentenced for violating this decree and other acts in an effort to gradually eliminate the party. In 1998, when the NLD called for the 1990 parliament to be convened within sixty days, 700 NLD members were detained, including 194 elected members of parliament.

6

Those who organize protests or create links between opposition groups receive even longer prison terms. Thet Win Aung, for instance, was sentenced to fifty-nine years in prison for helping to organize peaceful demonstrations calling for student rights and the release of political prisoners and for having contacts with exile organizations. He had previously been imprisoned in 1991 and, after his release, he spent some time in Thailand before deciding to return to Burma to continue his activism. He died in Mandalay Prison in 2006 at the age of thirty-four.

7

In 2005, Hkun Htun Oo, the chairman of the Shan National League for Democracy, who kept in regular contact with Shan ceasefire armies, was sentenced to ninety-three years in prison for attempting to form a Shan umbrella group. The regime was also unhappy with his closeness to the NLD and his party’s support for NLD policies.

From 1990 until 2007, Burmese prisons held over one thousand political prisoners at any given time, as released prisoners were replaced by newly arrested activists and political party members.

8

After the arrests of participants in the 2007 monks’ demonstrations, the political prisoner population increased by several hundred to over 2,100 in late 2008.

9

As of 2006, there were forty-two prisons and ninety-one labour camps in Burma.

10

Most political prisoners end up at one of the dozen larger prisons, and are frequently incarcerated in the same rooms as criminals. Political prisoners arrested in the Rangoon area are sent to Insein Prison, on the outskirts of the city. Many are later transferred to prisons upcountry, however, which makes it difficult for family members to visit. This causes great hardship because prisoners are dependent on their families for supplemental food and medicine. The very poor quality of the prison food and the lack of access to proper medical care take a great physical toll on many prisoners. HIV has also spread in Burma’s prisons, in part, say former prisoners, because hospital needles are reused without being sterilized.

11

According to the political prisoners I interviewed, drug

addicts are often allowed to work in the hospitals, giving injections to themselves and other prisoners.

Although criminals are more likely to be sent to the front lines as porters and to labour camps to work in quarries and build roads, a few political prisoners have also faced these punishments.

12

According to Amnesty International, hundreds of labour camp prisoners have died from untreated injuries and illnesses, malnutrition and ill-treatment.

13

A group of former political prisoners who formed the Assistance Association for Political Prisoners (AAPP) in Thailand have documented the deaths of 137 political prisoners between 1988 and late 2008.

14

This includes people who died during interrogation, in prisons and labour camps, and within a short time after being released.

Nevertheless, perhaps the hardest thing for many political prisoners to accept is that they are considered criminals. From their perspective, they are exemplary citizens who are struggling against injustice for the good of their country. To have to wear a prison uniform, squat and bow their heads when prison authorities approach, and often to have to share cells with real criminals, is highly insulting.

While political activists are in prison, the military intelligence and prison authorities try to destroy their morale, so that after they are released they will not participate in resistance activities again. In Myingyan Prison, for instance, one group of political prisoners was ordered to spend hours catching flies, shining the iron cell doors, and ‘polishing’ the bare ground in their cells with the base of a small bottle. Those who are particularly charismatic or dare to lead strikes inside prison are left in solitary confinement for months or, in the case of student activist Min Ko Naing, years at a time. If political prisoners do not literally go mad or become numb from being repeatedly degraded in various ways, they may resort to informing on their comrades in return for special privileges that make life in prison bearable. For those who are trying to maintain their commitment, it is disheartening to see fellow prisoners deteriorate psychologically or give up their political ideals for material comforts.

Torture and maintaining morale

U Hla Aye, a poet who was imprisoned in the BSPP period for anti-government activities, found the mental tortures at the interrogation centre as painful as the physical tortures. When he was interrogated in the heat of the summer, he was stripped naked, covered in salt and beaten. He and other colleagues were also forced to stand barefoot on heated iron sheets to burn the soles of their feet. Most horrible were

the electric shocks. He explained, ‘They did it to our genitals so that we became disfigured.’

Besides the pain, the authorities used humiliation. U Hla Aye said: ‘The authorities were acting under the belief that there are no political prisoners. Everyone is a criminal. That’s the simplest form of torture in prison.’ In the interrogation room, he and others were forced to pretend they were riding aeroplanes and motorcycles, making all the accompanying noises as if they were small children. Intelligence operatives also tried to depress him and other political prisoners by telling them their wives had taken other lovers or that their mothers were about to die.

Once he had passed through the interrogation centre, he was sent for trial. Rather than being held in a courtroom, the trial was conducted at the entrance of the prison, with the judge reading out his sentence according to the instructions given by military intelligence personnel. Then he was taken into the prison, where, he says, the military intelligence ‘instructed the prison wardens to break our spirits’.

While U Hla Aye was held at Insein Prison, he was frequently summoned for further interrogations. In order to make them talk, they would be left naked for several days in a tiny cell full of faeces and maggots. U Hla Aye managed to keep himself together during his experiences in this cell, but some of his colleagues suffered mental breakdowns.

U Hla Aye and some other inmates were later moved to Thayawaddy Prison, a three-hour drive from Rangoon. At first many of the prisoners’ families didn’t know where they had been sent. Even after they found out, it was hard for them to travel there. U Hla Aye recalled: ‘It was just to create more difficulties for living and eating. It is a form of torture intended to make groups of political prisoners become fed up with politics.’