Loamhedge (33 page)

Authors: Brian Jacques

Cowering fearfully against the battlements, the rat who had been crouching beside the victim babbled out. “I saw it, Cap'n! Gornat was 'it by summat from be'ind. There 'tis, see, one o' those liddle bags o' pepper, tied on a string, wid a stone at the other end!”

Bol unwound the object from around Gornat's waist. “From be'ind, this thing got 'imâye mean from the Abbey?”

The Searat nodded vigourously. “Aye, it came from over that way, I swear it, Cap'n. Pore Gornat got a terrible smack from it, the thing 'it 'im an' wrapped right round 'is waist. It musta cracked a rib, 'cos Gornat shouted an' jumped up. That's when the arrer took 'im, straight through the neck!”

Turning to face the Abbey building, Raga Bol saw another of the missiles come whirling through the air. It spun round and round on its twine, weighted on one end by the pepper bomb and on the other by the stone. This time it missed and struck the wallside. The pepper bomb burst, sending its load over two rats crouched directly beneath. One had the sense to stay down and do his sneezing. The other leaped up and sneezed once, then an arrow silenced him for good.

Â

Down in Great Hall, the Redwallers had unblocked the shutters from one of the tall windows.

Toran took the windowpole from Brother Gelf. “Can I try yore new slingpole out, Brother?”

Gelf smiled quietly. “Be my guest, sir.”

Laying the twine across the hooked metal end of the pole, the ottercook raised it straight up, facing out of the window. Holding the end of the pole in both paws, he let it lean back across his shoulder until it lay flat. Then he whipped it upright with swift force. The missile flew off through the high open window. There was a short interval of silence, followed by an agonized screech.

Toran grinned. “It works!”

There was no shortage of the homemade weapons. More window poles were brought, and more volunteers came forward, eager to try out the new weapons. Competition became so fierce that, owing to several of the defenders hurling the missiles at the same time, some of them missed the open window space. These projectiles struck the walls and lintels, bouncing back into Great Hall and bursting. Undeterred, the Abbeybeasts kept going, muffling their faces with towels. Soon, however, the atmosphere proved too much for the onlookers; many fled the scene, sneezing uproariously.

The Dibbuns thought the whole thing was huge fun. They chortled and giggled, dashing about and bumping into one another, shouting, “Hachoo! Blesha! Harrachoo! O blesha blesha!”

Martha helped Abbot Carrul and some of the elders to shepherd the little ones downstairs into Cavern Hole. The haremaid actually carried two Dibbuns down the steps on her back, chuckling and joking with them.

The Abbot cautioned her. “Careful, Martha, should you really be doing that? You don't want to put too much strain on those limbs!”

Martha deposited the Abbeybabes in a corner seat. “Oh fiddledeedee, Father, I feel stronger than I've ever felt. It's as if I had brand-new footpaws and legs, they're as supple as greased springs!”

Granmum Gurvel sent down some kitchen helpers to carry baskets of fresh-baked tarts and pastries and jugs of sweet elderflower cordial.

Martha lent a paw to serve the Dibbuns, then went to sit on the stairs with the Abbot. She felt very happy and carefree as they shared the food. “Oh Father, isn't it wonderful, having that giant badger on our side! I wager things will be different now.”

The Abbot seemed somewhat thoughtful, though he agreed with her. “Yes, indeed, those Searats obviously fear the big badger a lot. Wouldn't it be marvellous if he were inside the Abbey with us? Things would be so much easier.”

Martha sipped her cordial. “In what way?”

The Abbot warmed to the subject, propounding a theory which had been growing in his mind ever since he had first sighted Lonna standing out on the flatlands.

“Our badger fires that bow like a mighty warrior, that's for certain. If he were inside the Abbey with us, I guarantee he'd send those Searats packing in short order.”

Martha thought for a moment about what the Abbot had said. “Aye, he could stand at the dormitory windows and pick the Searats off at his leisure. They're hemmed in by the outer walls, so it would make it hard for them to avoid him. The badger could use the upstairs windows on all sides.”

Abbot Carrul put aside his food. “But the problem is that the badger's outside the walls at the moment. Those Searats aren't stupid, they're not likely to leave Redwall and take their chances outside. Not with that giant and his bow waiting for them.”

Martha saw the wisdom in her Abbot's logic. “Hmm, that could make Raga Bol doubly dangerous to us because he'll probably try twice as hard to get inside the Abbey now. It would give him an advantage over the badger, who would have to fight his way into the grounds and take the Searats on from inside the grounds. That would place him in range of their weapons. Oh dear, I wonder what the answer is to all of this!”

Carrul had already anticipated the problem. Unfortunately, he could not hold out a great deal of hope. “We need to contact our badger friend and get him inside here, but that's not possible. The Searats are standing between him and us. We'll just have to wait our chance, though there isn't much likelihood of that at present.”

Martha tried to hide the frustration in her voice. “But there won't be a much better opportunity than right now. Most of the Searats' attention is on the badger. If only we had somebeast who could slip out unnoticed! Whoever it was could leave by the small eastwall gate. They'd be shielded from any attention by the Abbey building. It wouldn't be hard to steal through the woodlands to the corner of the northwest wall. When it got dark, it would be simple to creep out onto the flatlands and make contact with the badger. Then they could both return the same way.”

The Abbot folded both paws within his wide habit sleeves. “No, 'tis far too risky at the moment, Martha. We'll waitâtomorrow, perhaps. Oh dear, all this worry and strife. I'm longing for the day when those villains are long gone from Redwall and we can all get back to a normal, peaceful life.”

Martha stood up. “Don't fret, Father, it'll happen when you least expect it. Do you know, I feel restless. Think I'll exercise my new walking skills. I'll go up to the dormitory windows and see how things are going. Best steer clear of Great Hall, and all those pepper bombs bursting inside.”

The Abbot smiled wearily at his young friend. “Take things easy, Martha, don't go tiring yourself out.”

She paused on the stairway. “Oh, I'll go as slowly as Old Phredd. By the way, Father, could you do me a favour? Will you sit guard on these stairs and make sure those Dibbuns don't go rushing back to Great Hall?”

Abbot Carrul stretched himself lengthways across the step. “Certainly. I might doze off a little, but they won't get past me. You go on now, and remember what I said about taking things easy!”

However, taking things easy was the last thing on the young haremaid's mind. Martha had a mission: she would be the one to contact the badger. She went up to the back rooms on the east side, choosing one that was mainly used as a linen store. It was filled with blankets, sheets and tablecloths.

Knotting bedsheets together, she fashioned a makeshift rope, reasoning aloud to herself. “Finally I can do something useful to help Redwall. Now I can walk, and run, too. After

all those seasons stuck in a chair, it would be a crime to waste my new gift!”

Climbing down the rope was easier than the haremaid had imagined. She had forgotten how strong her grip had become from wheeling a chair about for most of her life.

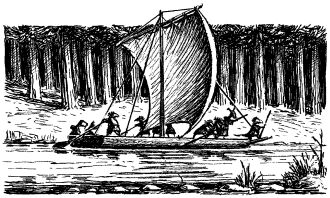

Dawn light seeped over the river, casting a haze of pale green-gold mist. Saro lounged in the stern of the main logboat with Bragoon, savouring the new day, and a few scones still warm from early breakfast.

“Ah, this is the life, mate, save the wear'n'tear on me ole footpaws. There's nothin' like a nice lazy rivertrip, eh?”

The otter grinned as Horty approached them, pushing on a hefty oarpole, part of two double lines of shrews. The young hare turned and started to make his way back to the prow, where he would repeat the process of poling the craft upriver.

He glared at the otter's cheery face and stuck his tongue out insultingly at Saro. “Blinkin' idle bounders, sittin' on your bloomin' tails, wallopin' down scones, while I slave m'self into an early grave. Huh, should be blinkin' well ashamed of y'selves!”

Briggy left the prow and strode down the centre of the logboat, between both lines of polers. Exchanging a sly wink with Bragoon and Saro, he clipped Horty lightly across the ears, roaring at him in true rivercraft language, “Avast there, ye long-legged layabout, quit prattlin' an' git polin'. We gotta build those muscles up t'make a warrior of ye! Ain't it a wunnerful life, nothin' t'do but pole about all day on the river, ye lucky swab! Dwingo, give us a drumbeat there. Come on, shrews, put yore backs into it. Sing out a polin' shanty to speed us on our way. Push, ye shrinkin' daisies. Push!”

The drumbeat rolled out, echoing around the forested banks, with deep, gruff shrew voices singing in chorus. The shanty was a totally untrue pack of insults about Log a Log Briggy, but he sang along with them lustily.

Â

“Barrum, babba, whum! Pole to the beat o' the drum!

Our Cap'n is a bad ole shrew,

I wish I'd never signed to roam.

He feeds us worms an mudpies, too,

oh ma, let me come sailin' home.

Barrum, babba, whum! Pole to the beat o' the drum!

Â

Ole Briggy is a lazy hog,

wid a belly like a tub o' lard,

if we don't call 'im Log a Log,

he beats us bad an' treats us hard.

Barrum, babba, whum! Pole to the beat o' the drum!

Â

One day our logboat sprang a leak,

an' I gave out an 'earty wail,

the Cap'n gave me nose a tweak,

an' plugged that leak up wid me tail.

Barrum, babba, whum! Pole to the beat o' the drum!

Â

We ran head-on into a gale,

our Cap'n made me cry sad tears,

'cos the wind 'ad ripped right through the sail,

so he patched the canvas wid me ears.

Barrum, babba, whum! Pole to the beat o' the drum!

Â

Ye've heard me story, messmates all,

an' if I spoke a lie to you,

may me nose swell into a fat red ball,

an' me bottom turn bright green'n'blue.

Barrum, babba, whum! Pole to the beat o' the drum!”

Â

Horty was astonished; he turned to the shrew behind him. “By the left! I say, old chap, are you allowed to bandy insults like that about Briggathingee, wot?”

The shrew kept poling as he gave Horty a broad wink. “It ain't serious, mate, 'tis all done in good fun!”

Briggy saw Horty gossiping and descended upon him.

“Stop jawin' an' keep pawin', rabbitchops, or I'll 'ave yore whiskers for desksweepers!”

The young hare gave Briggy a cheeky grin and launched into a barrage of insults. “Oh shut your blatherin' cakescoffer, y'great bearded windbag! You sound like a duck with a beakache, hasn't anybeast ever told you? Hah, tush'n'pish for all your ilk, sah, you wobble-pawed, twinky-tailed excuse for a barrel-bummed toad. Who d'you think you're jolly well talkin' to, you wiggle-whiskered, bawlin' braggart!”

Horty turned back to the shrew he had spoken to previously. “Pretty good, wot! That told old Log-a-pudden a thing or two!”

The ashen-faced shrew hissed back at him. “We only ever does it in songs, all t'gether like. If'n you speak like that, face t'face wid a Log a Log o' Guorafs, that's mutiny, mate!”

Horty turned round to find Briggy looming over him with a face like thunder.

The force of the shrew chieftain's roars made Horty's long ears flap. “Mutiny, eh? I won't 'ave mutineers aboard my logboat! Grab 'old o' this mutinous beast, put 'im to task! No more rations for 'im while he's on this vessel!”

Four shrews frogmarched the hapless hare off to the stern where he was given a large sack of wild onions to clean and peel.

Bragoon made his way to the prow, where he had a quiet word with the shrew chieftain. “Ye were a bit 'ard on Horty there, mate. The young 'un wasn't wise to yore rules an' reg'lations, he thought 'twas all a bit of a joke. Horty didn't mean ye no real insult.”

Briggy's eyes twinkled. “I know he didn't, friend, but I said I'd toughen 'im up. If'n that young 'un ever expects t'join the Long Patrol, he's gotta learn manners an' curb his tongue. Could ye imagine one o' those hare officers from the Long Patrol lettin' a recruit speak to 'im like that? Joke or not, some stiff-eared sergeant would clap 'im on a charge an' use 'is guts fer garters!”

Bragoon agreed. “Yore right, Briggy, a bit o' discipline wouldn't 'urt 'im. All three o' them young 'uns've been livin' the soft life at Redwall fer too long. The two maids are much better be'aved than Horty, they'll lissen t'reason. But Horty's

too wild an' 'eadstrong. One day he'll make a fine warriorâafter he's learned a few stern lessons.”

Briggy stroked his beard. “Don't fret, mate, I'll knock all the rough edges off'n Horty. My Jigger was the same 'til I showed 'im the ropes. Lookit Jigger now, commandin' his own logboat. There's a young shrew anybeast'd be proud t'call son!”

The otter went back astern and sat with Saro. Behind them Horty was weeping buckets as he peeled and chopped the pungent wild onions. He went at it with vim and vigour, though scowling and muttering about the injustices of life aboard a logboat.

“Bit flippin' thick this lot, wot? A few measly words to old Brigalog an' he treats a chap like a bloomin' vermin marauder! I mean, what did I say? The bearded old buffer should count himself jolly well lucky, wot! Oh, yes indeed, when Hortwill Braebuck Esquire starts really chuckin' insults, he could roast the flamin' ears off a milky-whiskered shrew. I could've called the chap a lot worse! Twiggle-jawed trout! Giddy-nosed toad! Pickled old pollywog! Witless water beetle! Puddle-pawed duck's bottom! Or even Skinnyforlinkee Wobblechops! Huh, I think I let him off lightly, really. Good job one can hold one's temper, wot wot!”

Log a Log Briggy came striding down between the polers. “Ahoy there, mates, is that mutineer be'avin' hisself? I might let 'im get a bite o' supper tonight, if'n I 'ears an apology.”

Bragoon nudged Horty. “Did ye hear that, matey?”

The young hare turned a face, still running onion tears, to the Guoraf chieftain and declared dramatically, “Y'mean you'd restore my scoffin' privileges, sah? Merciful Logawotsyaname, I'll peel every last one of these foul fruits, I swear I will. Good Captain, I'll be the saltiest young riverbeast you ever clapped eyes on. Listen to this. Shiver me sails an' rot me timbers, fry me barnacles, scrape me keel, an' all that nautical jimjam. You, matey sah, are lookin' at a completely reformed beast!”

Briggy glanced at Saro. “Wot d'ye think, marm, is that a rogue worth feedin'?”

The aging squirrel saw the haunted look in Horty's eyes and took pity. “Aye, Cap'n, only a moment ago Horty was sayin' wot a good ole Log a Log ye are. Ain't that right, Brag?”

With difficulty, the otter kept a straight face. “Right enough, I'd give 'im another chance if 'twas up t'me.”

Briggy stroked his beard a moment, before answering. “Aye, so be it then. Leave those onions now, young 'un, go amidship an' lend the cook a paw in the galley.”

Horty galloped off, overjoyed at the prospect of working amid food. “Help the cook, I say, what a spiffin' job! A thousand thanks to you, Captain Briggaboat, an' you, my two chums. You have a handsome young hare's undying thanks!”

Bragoon chuckled. “Same modest Horty, eh?”

Â

Aboard Jigger's logboat, Fenna and Springald were being treated like royalty. Fenna had also gained an admirer, a stout young shrew named Wuddle. Both he and Jigger could not do enough for the pretty Redwall maids. The shrews brought extra cushions, erected an awning to shade them from the sun and served more delicious snacks than both of them could possibly eat. Then the two creatures vanished momentarily, to reappear grinning awkwardly, carrying with them two accordionlike instruments, which they said were called shrewlodeons. Jigger and Waddle twiddled a few keys, then launched into a song. Springald and Fenna were convulsed with laughter at the faces that both shrews pulled while singing. On verses they would be scowling savagely, whilst on the choruses they adopted expressions of peaceful concern. Both had wonderful bass voices and sang in harmony.

Â

“When I meets a beast wot ain't polite to laydeez,

I grabs 'im round the throat 'til he turns blue,

I holds him tight in check as I squeezes on his neck,

then I boots his tail three times around the deck!

Â

'Cos be they sisters mothers aunts or daughters,

all laydeez must be treated tenderly,

they're dainty an' they're neat, an' they don't have much to eat,

an' they rouses gentle feelins within me.

Â

When I'm around an' you insults a laydee,

I'll jump on yore stummick very forcibly,

then I'll punch you in the snout an' I'll prob'ly knock you out,

an' black both of yore eyes so you can't see!

Â

'Cos be they sisters mothers aunts or daughters,

all laydeez must be treated tenderly,

they're dainty an' they're neat, an' they don't have much to eat,

an' they rouses gentle feelins within me.

Â

So mind yore manners an' be very careful,

when in the company of laydeez sweet,

or I'll shove you in a sack, after fracturin' yore back,

an' I'll stamp upon yore paws if you gets free!”

Â

After the final chorus, they escorted both maids on a pleasant promenade of the deck, snarling fiercely at any of the poling shrews who dared to look sideways at Fenna or Springald.

Â

Supper on a mossy bank, overhung by weeping willows, was a total success. It was all due to Horty's onion soup. The Guorafs congratulated him on his cooking skills. He lapped up any compliments with a complete lack of modesty.

“Tut tut, nothin' to it, dear chapsâa pinch o' this, a smidgeon o' that an' a sprinklin' of the other. Plus, of course, blinkin' loads of those confounded onions. I tell you, I shed many salt tears into the recipe, wot! Wild onions? Hah, I wasn't too blinkin' pleased, havin' to tame 'em down for you lot. I'd sooner be skinned me bloomin' self than have to skin another wild onion!”

Log a Log Briggy watched the young ones cavorting, singing and playing, then lay back and stretched. “Beats me where they find the energy! Ah well, let 'em be merry while they can, 'specially those three young 'uns o' yores. I reckon we'll make our voyage end by midmorn tomorrer. That's when all the fun'n'games will finish for Horty an' the maids. I'm glad I don't have t'make the slog over desert an' gorge to Loamhedge with ye. That's country I was never fond of.”

Bragoon flicked a twig into the fire. “They'll do alright, with me'n my mate to look after 'em.”

Saro smiled. “Aye, but by the creakin' o' my ole bones, 'tis

them who'll be lookin' after us by the time this liddle jaunt is finished!”

Next morning, they arrived on time at the spot, just as Briggy had predicted. It was indeed hard, arid country. They had been sailing upriver since the crack of dawn. Nobeast could fail to notice the difference in the terrain. Trees, bushes and grass thinned out along the banks, whilst a hot breeze wafted in dust from the wastelands.

Briggy smiled at the young creatures' downcast faces. “Cheer up, mates, it ain't good-bye just yet. We'll be moored alongside this bank when ye come back wid a cure for Horty's sister. Get goin' now, an' good fortune go with ye!”

“Thanks for everythin', ole friend!”

“Aye, we'd a-been in a right pickle widout you an' yore crews, matey.”

“See ye in six days, eh!”

Loaded with shrew hardtack biscuits and two canteens of water apiece, the travellers set off into the unknown.

Briggy called out as the logboats pulled away. “Keep the sun on yore right cheek, ye'll see the Bell an' Badger Rocks afore dark. But y'won't be able to reach 'em until ye figure out 'ow to cross the great gorge!”