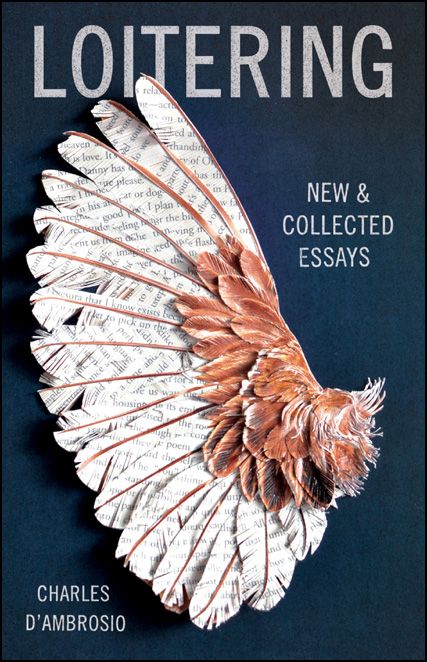

Loitering: New and Collected Essays

Read Loitering: New and Collected Essays Online

Authors: Charles D'Ambrosio

PRAISE FOR CHARLES D’AMBROSIO’S ESSAYS

“. . . Powerful . . . highlights D’Ambrosio’s ability to mine his personal history for painful truths about the frailty of family and the strange quest to understand oneself, and in turn, be understood.”

—

Publishers Weekly

, Starred Review

“Erudite essays that plumb the hearts of many contemporary darknesses.”

—Kirkus

“D’Ambrosio hasn’t published anything less than brilliant, but

Loitering

is remarkable even by his standards.”

—MICHAEL SCHAUB, the

Portland Mercury

“As is the nature of his brilliance, D’Ambrosio resists conclusions. He honors the complexity embedded in his grief—not always a source of solace, but ultimately a powerful kind of tribute.”

—LESLIE JAMISON, Flavorwire

“By turns witty, scathing, and elegiac, his exacting essays are exceptionally vital quests for meaning, and Seattle-based D’Ambrosio chooses his loaded subjects well, writing with nerve and rigor, for instance, about the controversy over Native American whaling and teacher and convicted sex-offender Mary Kay Letourneau. D’Ambrosio’s kinetic and evocative works reach to the very core of being and induce readers to question their every assumption.”

—Booklist

“

Orphans

is a remarkable non-fiction collection, always intriguing, often surprising . . . D’Ambrosio is a major league talent.”

—the

Seattle Post Intelligencer

MORE PRAISE FOR CHARLES D’AMBROSIO

“Charles D’Ambrosio works a rich, deep, dangerous seam in the brokenhearted rock of American fiction. His characters live lives that burn as dark and radiant as the prose style that conjures them, like the blackness at the center of the candle’s flame. No one today writes better short stories than these.”

—MICHAEL CHABON, Puliter Prize–winning author of

The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay

“It is astonishing that a writer with [D’Ambrosio’s] depth and agility is not a household name. But that, it seems, is about to change.”

—Bomb

“These evocative stories are dark and graceful, as deeply nuanced as novels. D’Ambrosio evokes lives of regret and resignation, and there’s never a false note, only the quiet desperation of souls seeking the elusive promise of redemption.”

—the

Miami Herald

“D’Ambrosio spins out descriptive lines or dialogue strong enough to lift the entire edifice of a story with a shudder.”

—Chicago Tribune

“D’ambrosio . . . should be ranked up near Carver and Jones on the top tier of contemporary practitioners of the short story.”

—Los Angeles Times Book Review

“The stories that make up

The Dead Fish Museum

are lithe masterpieces of emotional chiaroscuro.”

—Elle

Copyright © 2014 Charles D’Ambrosio

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. For information, contact Tin House Books, 2617 NW Thurman St., Portland, OR 97210.

Published by Tin House Books, Portland, Oregon

and Brooklyn, New York

Distributed to the trade by Publishers Group West, 1700 Fourth St., Berkeley, CA 94710,

www.pgw.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

D’Ambrosio, Charles.

[Essays. Selections]

Loitering : new & collected essays / Charles D’Ambrosio.

pages cm

ISBN 978-1-935639-88-6 (ebook)

I. Title.

PS3554.A469A6 2014

814.54—dc22

2014014455

First U.S. Edition 2014

Interior design by Jakob Vala

For all the conversations over the years this book goes out to Drew Bouton, Jon Fontana, and Tom Grimes; and I also send it along with love to some dear people who talked me up, talked me down, and talked me through, Marilyn Davis, Jae Choi, and my sisters; and of course the soul of the book belongs to Mike and Danny, my brothers, who will never read a word of it, though their silence tunes every sentence I write.

CONTENTS

PART 2:

STRATEGIES AGAINST EXTINCTION

Any Resemblance to Anyone Living

Degrees of Gray in Philipsburg

There’s an old bus stop in Seattle that’s maybe the loneliest place in the world for me, and it was there, reading in the vague light, that I first discovered the essay. Even now when I drive by, I still check that stop, looking for one of my brothers or sisters, although the stop itself has been moved to a better location and the family I might give a lift to is gone. By the standards of the day it was an excellent place to wait for the bus, really the stoop of an apartment, with a marble stairway that was cold but covered, offering shelter from the wind and the rain and a lighted entry that was just bright enough to read by. You had to sit on the top step and slouch over and futz with the book to get the angle, but once you had it, the words resolved on the page. As a bonus

there was a bookstore across the street that stayed open late. It was one of those small places that made up for a lack of inventory with sensibility, a bookstore you could trust, and the first that I knew of to hand out free bookmarks, which I thought at the time was infinitely clever. I had just figured out, rather naïvely, that I could buy my own books, and then almost instantly I became a prig about their condition, so much so that I wouldn’t lend them to anyone, at least not without a solemn lecture about their proper handling: no breaking the spines, no dog-earing the pages, no greasy thumbprints. At home, I had my own somewhat wobbly arrangement of brick-and-board shelves, two and then three tiers of ugly pressboard, painted brown and laddered up against the wall, my first piece of furniture. In private, I thought of those shelves with enormous pride, as something I was building, book by book, and brick by brick, and I often looked at them, vaguely satisfied, like a worker inspecting the progress of a job. I wanted the shelves to rise up and reach the ceiling, and for that to happen, all I had to do, I realized, was read.

My sense of the essay as a genre isn’t something I can separate from my experience of those early encounters. I bought my first collection from that little bookstore, on their recommendation, and fell in love with the writer M. F. K. Fisher, whose works on gastronomy

couldn’t have been more foreign to me, growing up, as I did, in a big family, where we boiled everything in vats, drank powdered milk, and my father, fielding a complaint about food, would clench the fist of his free hand and stab his fork at the offending item on his plate and say, “Eat it. Your stomach doesn’t care.” Well into adulthood I was too shy to pepper food at a restaurant, afraid that I would somehow be insulting the cook. Anyway, it was at family meals that we learned indifference to our bodies, but it was in prose, particularly the kind I found in the personal essay, that a relationship to that body began to be restored, at least for me. One of my earliest ideas about writing was that the rhythms of prose came from the body, and although I still believe that, I still don’t know what I mean. I would discover, eventually, that some of Fisher’s love of food was a celebratory rebellion against a similar tyranny at home, a rejection of the dulling rules and sumptuary restrictions of the dinner table set by her grandmother. Prose moves so mysteriously that I believe I heard this unstated fact in the rhythm of her sentences long before her biography confirmed it. It came to me sotto voce, whispered on a lower frequency, a secret shared between intimates. And so, while the superficial subject of Fisher’s essays may have drawn me in, offering a fantasy world in which foie gras and Dom Pérignon mattered, soon enough it

was language itself, and more specifically, the right she assumed to be exact about her life, that won me completely. More than the wonders of Provence or advice on how to serve peacock tongues on toast, it was her prose that taught me how to pay attention, and it was the essay, as a form, that was the container, the thing that caught and held the words like holy water, offering the gift of awareness, the simple courtesy of acknowledgment, even to a life as ordinary as mine.