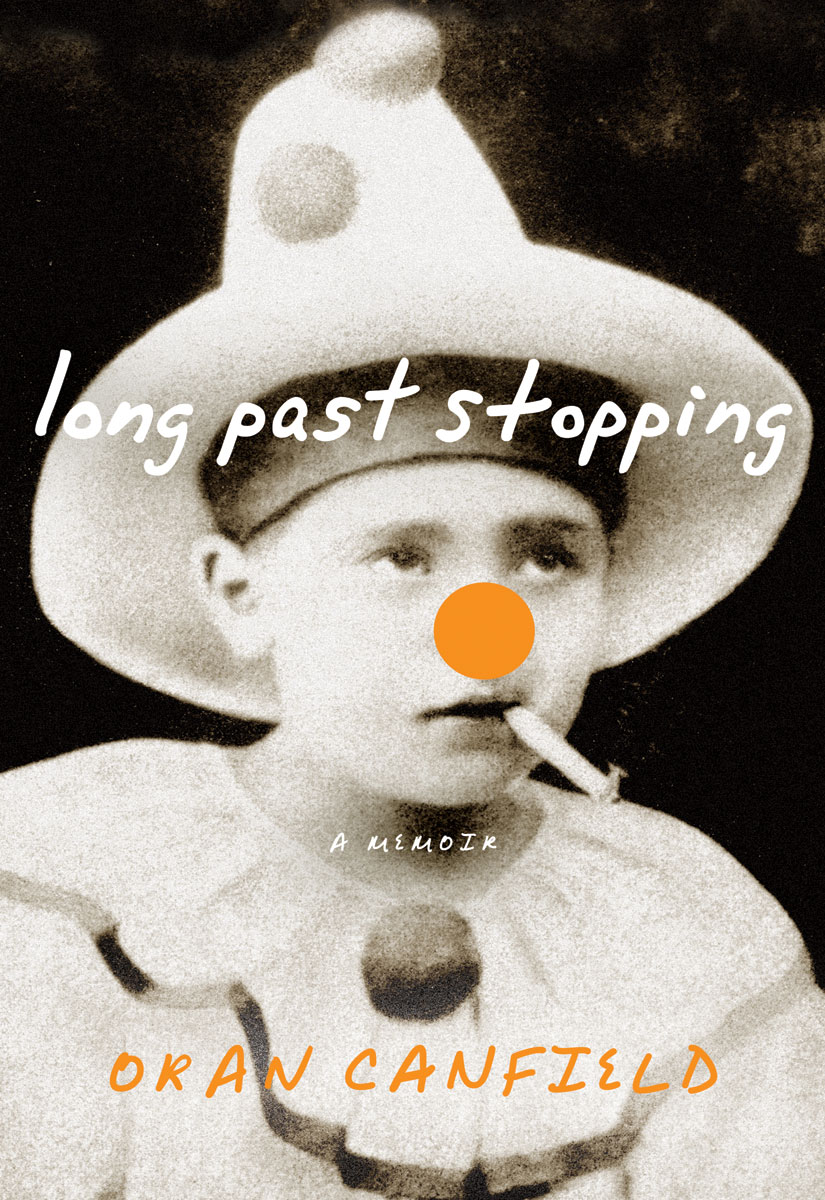

Long Past Stopping

Read Long Past Stopping Online

Authors: Oran Canfield

A Memoir

For Kyle and Christopher

In which our speaker begins to weave his yarn in a cellar full of strangers

In which our protagonist sets foot in this world, survives a nuclear meltdown, and learns the secrets of juggling from a traveling group of hippies

In which a young man is introduced to the pleasures of a dark substance, through the benevolence of a learned professor

The adventures and misdeeds of the boy and his brother on a dirt lot in New Mexico

Tells of how the young man came to be enslaved by the mighty god Chiva

Wherein the boy encounters a holographer, a born-again Christian, and his Jewish grandmother, and lives to tell about it

In which he meets a girl and accidentally exposes his terrible secret

In which the boy finds himself living among misfits, radicals, anarchists, and robots while performing daring feats with a band of clowns

In which our subject tries to escape from the powerful clutch of Chiva, and is transformed into a bull-person

Is where he gets some new clothes

Tells of a series of bad decisions, which lead to a terrible fall

In which the young boy comes upon an evil dictator, and starts a revolution

A reconstruction of confounding events, as our protagonist tries to escape the noble intentions of his friends and family

In which the boy finds himself in trouble with both sides of the law

Sees our protagonist stand his ground against a pack of fanatical well-wishers

Presents evidence that extracurricular activities lead to communism

In which the young man is caught in a torrential downpour of fecal matter and encounters pure evil in the form of a rock

In which a journey to the outlands finds our protagonist in the back of a cop car sniffing a curious white powder

By what low road he arrived at his father's house

On how he came to eat a bit of paper that is said to open minds

Recounts a daring heist from the police and a subsequent visit to the psych ward

In which he is saved from untimely death and avoids broccoli and zucchini through his own resourcefulness

Is long, but holds the reader's interest through a series of comical interludes

In which a no-handed woman learns to juggle, and a son halfheartedly bats a pillow

Shows the disastrous consequences of a walk to the store

Mostly concerns the uncomfortable topic of sex

In which a learned doctor tells our subject about the god Iboga, enemy of Chiva

In which the boy sets out to become a man, but does a terrible job of it

Chronicles the journey to a faraway isle in search of the mystical god Iboga, who reveals the identity of our subject's true nemesis to be none other than himself

In which our speaker brings his audience up to date

Â

In which the author finds himself strapped to a chair in a dark basement and is being questioned by an unseen man who is blinding him with a flashlight while someone else is pouring buckets of cold water on him

OKAY, MR. CANFIELD

. I'm going to ask a few questions and I just want you to answer true or false.

Â

So this story is all true?

TRUE

Â

So, you didn't change a name here? An identity there? All the circumstances are accurate?

FALSE

Â

You changed some of the names and identities to protect people's privacy?

TRUE

Â

What about the dialogue? All of the conversations are recounted word for word?

FALSE

Â

Now we're getting somewhere. Have you written the conversations in a way that captures the feeling and meaning of what was said, in keeping with the true essence of the mood and the spirit of the events?

TRUE

Â

So, let me get this straight. You have admitted that some of the names have been changed and that the conversations are not word for word, but still you insist that this is all true?

TRUE

Â

And what about this conversation? Did this really happen?

FALSE

In which our speaker begins to weave his yarn in a cellar full of strangers

U

Mâ¦MY NAME'S ORAN,

and⦔ I begin to say into a microphone, before cringing at the sound of my own voice and then drawing a complete blank. My whole day has been spent obsessing on what I'm going to say, and even though I've done this a few times, I'm still deathly afraid of speaking in front of people. My mind is jumping all over the place from my childhood, to my drug-using period, to the last seven years in which I've managed to stay clean, and back again.

It's a hell of a lot to think about, and I have no idea where to start, until someone in the front jars me out of it by whispering, “Start at the beginning.”

In which our protagonist sets foot in this world, survives a nuclear meltdown, and learns the secrets of juggling from a traveling group of hippies

A

S FAR AS I KNEW,

life started when I was four. I don't have any memories from before that. It was as if I had walked into the theater halfway through the movie and had to pay extraspecial attention to figure out was going on.

There were three of us in a big house somewhere near Philadelphia, and there was a pool and a kitchen drawer full of sugar. The woman with the long dark braids wearing Guatemalan clothes was my mom, and the kid crawling around on all fours in a Guatemalan skirt was my brother, Kyle. There was another character who hadn't yet made an appearance, but his name came up almost daily. His name was Jack, and from everything I'd heard he was the lying, cheating, conniving, manipulative, inhuman son of a bitch who had left my mom when I was one and she was six months pregnant with Kyle. I didn't know what kind of clothes Jack wore, but in my imagination he had red skin and horns.

I watched and I listened, and Mom filled me in on the parts I had missed.

Â

I

WAS BORN AT HOME

in a small town in western Massachusetts, where my parents had recently opened up a holistic health center. Present at the birth were my mother, my father, a midwife, and ten Bud

dhist monks from the monastery up the road. The monks were there to chant throughout my delivery.

“Oh, it was so beautiful, Oran. Really just an amazing experience,” Mom told me when I was old enough to understand such things. “You were big, though. It took you seventy-two hours to come out and I had to go straight to the hospital afterward. When I got back, we ate the placenta.”

“You what?” I asked.

“Of course, honey. That's where all the nutrients are stored for the breast milk. Humans are the only mammals that don't eat the placenta after they give birth.”

I took her word for it.

“We've become so detached from nature we're losing our natural instincts. I mean, can you believe that people have their babies in hospitals, under all those fluorescent lights, and the first thing they do is spank you to make you cry? Then they take you away from your mother and they cut off your foreskin? It's barbaric. No way was I going to put you through that. Seriously, the very first thing they do is hit you and then cut off part of your penis.” The way she put it, it did sound like a pretty crappy reception.

“Did you cook it?” I asked about the placenta.

“Oh, yeah. We fried it up with some butter. It's kind of like steak.”

“Then what?”

“Well, you know, we were extremely busy running this business and taking care of a staff of twenty-five people, so all day you were passed around among the fifty or so people at The Center. Everyone loved you.”

In between leading primal or scream therapy sessions, Mom would breast-feed me, or Jack would walk around with me strapped to his chest reading poems he had written. But for the most part, a community of weird therapists, early self-help freaks, and drug-experimenting hippies took care of me.

“It was really an incredible time,” she said with a distant look in her eyes.

Â

A

YEAR AFTER I WAS BORN,

when Mom was pregnant with Kyle, Jack hooked up with the masseuse employed at The Center. He decided that my mom's birthday was as good a day as any to tell her he was in love with someone else and she should probably pack up and leave.

“I didn't know what to do,” Mom told me. “After the divorce, we got in the camper and I just started driving. I didn't know where to go, so we just drove around the country.”

Kyle was born in a hotel in Mexico, delivered by the town doctor. Mom decided that it might be nice to cook up the placenta with some onions and bell peppers this time. She invited Jack to come down and see his son, but she never got a response. She went back to the States just long enough to take care of Kyle's paperwork and was told by a pediatrician that he was most likely both retarded and a midget, but that it would be a few years before either was noticeable.

Devastated, aimless, and alone with two kids, she decided to continue south to Guatemala, because of a rumor that the Nestlé Corporation was trying to get the Indians to quit breast-feeding and use their scientifically engineered baby formula instead. We moved to an area called Panajachel on a huge lake surrounded by seven villages, each with its own language. With only gutter water to mix with the formula, these Guatemalan babies were dying from all manner of disease. Mom rented a house near a big lake and began her one-woman crusade against Nestlé.

In the beginning, she walked around from village to village wearing a Guatemalan dress and combat boots with Kyle strapped to her chest and me riding on her back. After a catastrophic earthquake that killed twelve thousand people, we were left at home while she went around educating the natives on the benefits of breast-feeding and the evils of American corporations.

“The earthquake was unbelievable,” she said. “You were fine, but Kyle almost died. He was only a few months old and his lungs couldn't handle all the dust in the air. When we got to the hospital, they tried to turn us away because they were so full, but when they saw Kyle, they agreed to take him in. We slept in the hall for three days. When we got back home, the house had been taken over by a bunch of Indian families who had lost their huts in the earthquake. It worked out, though, because they were more than happy to take care of you guys while I went out to work.”

I loved listening to these adventure stories, and I wished I could remember being there because they sounded like fun.

Â

A

FTER TWO YEARS

of living in Mexico and Central America, Mom was ready to come back to the States and start her own therapy practice in Philadelphia. For the first few months we lived in a house

that belonged to some friends of hers while she looked for a place to start her new therapy center. While we were there I managed to eat an entire drawer full of sugar. Mom thought I liked to climb on top of bookshelves and run around in circles because I was a curious and active kid. The truth was that I was high on the refined sugar that I ate by the handful. I knew it was wrong, but I couldn't help myself. When the high wore off, I'd find a closet or a cupboard to hide in.

We moved from there to an old three-story mansion she bought in the suburbs. In a matter of months her new center was teeming with clients. She liked the house because it was made of stone, and it was a stone house that had saved our lives in Guatemala when the earthquake hit.

The new house had tons of new closets and cupboards to explore. Mom would find me and ask, “Ory, what are you doing under the sink?” or “Hey, Oran, what's going on down there?” I'd poke my head out from under a bed, and she would just kind of laugh at me. If I really didn't want to be found, I would go into a closet and cover my whole body with a pile of clothes, but this would usually instigate some sort of panic and I would have to get out of the closet without being seen and find another hiding place where Mom

could

find me so I wouldn't have to answer any questions about where I'd been. She was confused when she found me in a spot she had already checked.

“Seriously, Oran. Is there something going on in there I should know about?” Mom would ask.

I didn't have an answer for her.

Â

I

LIKED MY SPOT ON THE STAIRS,

where I could watch Mom's clients come and go. It was right between the first floor and the landing. It faced the front door and gave me a view of the dining room on the right and the entrance to the conference room on the left. I found that I could just hide out inside of my head instead of the closet or cupboard. For the most part none of Mom's clients ever seemed to notice me there; it was almost as good as hiding in a cupboard.

That's where I was sitting when Jack walked in. When Mom told me he would be coming, I expected to see a monster with fangs and horns, but Jack looked just like everyone else who came to the house: khaki pants, tucked-in blue shirt, short hair.

We weren't big huggers around that house, but Jack came up with his arms open and, not knowing what to do, I mimicked him and found myself on the receiving end of his uncomfortably long embrace.

“Oran? I'm Jack, your father.”

“Hi” was all I could think of to say.

“You're getting so big I hardly recognized you. What are you, five years old now?”

“Four,” I answered.

“Where's Oran?”

“I'm Oran.”

“I mean Kyleâ¦your brother.”

“Outside,” I answered.

I was content to stay on the stairs while Jack went out to find Kyle, but Mom's face made it clear that I was to follow them outside.

“Hey, Oran. I hardly recognized you, you're so big,” he said to Kyle. Kyle glanced at him for a second before going back to playing with a pile of pinecones he'd collected.

“That's Kyle,” Mom said.

“I mean Kyle. Hey, Kyle, how old are you now?” he asked, walking over to him. Kyle wasn't doing too much talking yet and seemed not to hear him.

“He's three,” I answered for him.

“How can he be three if you're four?” he asked, visibly confused. Truth be told, I was confused about that, too. Some of the time I was two years older.

“They're eighteen months apart. Remember, Jack, how I wanted them to be close in age so they could be friends?”

Jack nodded, but it didn't look as if he remembered much of anything about us. I was surprised that Mom was being so nice to him considering all the time she spent ranting and raving about what an evil monster he was. “Can you imagine leaving your wife when she's six months pregnant and taking care of a one-year-old?” she often asked me. I always shook my head. “I really thought he was different. What a fool I was. They're all the same. He used to read me these love poemsâhe wrote wonderful poems, by the way. Then on my birthday he took me to the lake house, and that's when he told me he was sleeping with that blond masseuse, and I cried and told him we could work it out, and he said it was over, that he was in love with her. Can you believe it?” Again I shook my head.

That's about all I knew about this guy, and I was relieved when he left and I got to go back to my stairs.

Â

A

MONTH LATER THERE

was a meltdown at a nuclear power plant a hundred miles away, and, not knowing the extent of the damage, Mom wanted to get Kyle and me out of the area. Mom alternated between screaming and crying on her office phone. “These are your sons, Jack! Well, of course the government is going to say that, but no one really knows how bad it is. That's why you need to come down and get your kids out of here now!” She was still sniffling when she came out to help me pack up my stuff. “So, Ory, Jack has agreed to take you, and Grandma Ada is coming to get Kyle.”

“Why can't I go with Grandma?” I asked.

“Because you and Kyle need to start having a relationship with your father. I just thought maybe I was wrong about him and he would come get you guys, but he's too busy to take care of his own kids,” she said, choking up. “I had to plead with him just to get him to take you! Can you believe it?” I shook my head.

Â

O

NE OF JACK'S FRIENDS

picked me up from the train station, and a few days later Jack came and took me to the therapeutic center in Massachusetts that he and my mom had started. He was the main guy there, but beyond that I didn't have any idea what exactly he did. A bunch of adults would go into a room with him and emerge a few hours later. That part was no different from what my mom did in Philadelphia, and I felt lucky that, with two parents who fixed other people, I would never have any problems of my own.

I got to see the room I was born in, and the lake house where he told Mom it was over, and just as Mom had described it, Jack was so busy that I was passed around to the staff, who watched me for a few days until the experts declared that it was safe to return to Pennsylvania.

Â

W

HEN I GOT BACK, MOM

was concerned that sitting on the stairs all day wasn't good for me, so she hired a piano teacher, sent me to school, and tried to expose me to the arts, science, and nature. I couldn't understand what the problem was. Everything seemed fine to me, but she thought it was bad that I didn't talk to anyone and claimed that she had never seen me smile. She was right for the most part, but what was so bad about not smiling? Plus it wasn't totally true. Mom was a busy woman, running her new center, appearing on television, doing panel discussions, playing music. She was so busy she had to hire some

one to take care of us. I smiled when Laurel, our Jamaican housekeeper, would sneak Kyle and me into her room to let us watch TV and give us ice cream. Laurel would have been fired in a second if Mom found out she had given us something containing processed sugar, not to mention let us watch TV, so we kept it a secret.

Laurel worked her ass off for us, but she did get a couple of nights a week to go spend with her family. This was kind of traumatic for Kyle and me, because it meant no TV and ice cream after Mom left for the night to go play piano at one of her jam sessions. Bob, the psychoanalyst who rented a room upstairs, was always around, but we didn't like him too much. We would make the best of it by going through the stacks of records Mom would bring back from her trips to New York. She called it “rap” music, and Kyle and I could listen to these records for hours. We would memorize the lyrics and make up dance routines.

Like almost everything else that seemed normal to us, such as carob, tofu, macrobiotics, Rolfing, homeopathy, and Gestalt therapy, I didn't know anyone who had ever heard of rap music. Laurel hated it, though, and would go into one of her fits if she heard us listening to it. “Lord have mercy on my soul. Turn off dat racket, boys. I don't know what has become of black folks in dis country. Dey call dat music? And what you white boys listenin' to dis for? Your mother is a crazy woman, going to New York and carrying on the way she do. Lord have mercy on

your

souls is more like it. I'm going to pray for you boys. It's too late for your mother. Prayer won't help dat woman. I don't know what will.” We listened to Laurel in the same way we listened to our rap albums. It didn't matter what she was saying, we were mesmerized by the rhythm of her voice, her accent, and her way with words.