Long Road Home: Testimony of a North Korean Camp Survivor (9 page)

Read Long Road Home: Testimony of a North Korean Camp Survivor Online

Authors: Yong Kim,Suk-Young Kim

Tags: #History, #North Korea, #Torture, #Political & Military, #20th Century, #Nonfiction, #Communism

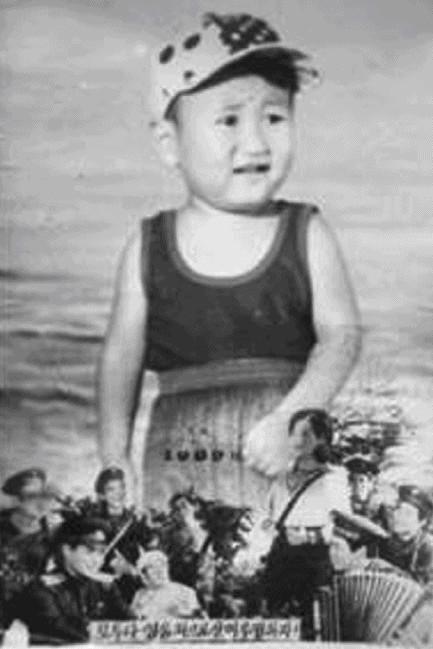

My son is one year old in this picture taken in 1989 in a photo studio in Pyongyang. At the bottom are various studio props featuring the images of happy North Korean youth. The caption at the very bottom reads: “Let us live a hero’s life and struggle [for the revolution]!”

My son and daughter had their picture taken together in Pyongyang on April 15, 1991, roughly two years before my arrest. It is a widespread custom in North Korea to take family photos on April 15—a national holiday celebrating Kim Il-sung’s birthday.

As soon as she could stand on her feet, I put her on my palms and she would stand still.

It is painful to recall that I was a father who wasn’t around too much. Most of the time, I was away on the road on business trips. Naturally I was an extremely poor babysitter. One summer evening when my wife was away and I had to take care of my infant daughter, she cried so much that I wrapped her in a blanket and held her loosely in my arms. She still kept crying, so I kept rocking her. Nevertheless, she started to cry even louder, so I got up from the sofa, walked around, and rocked her even harder. But by the time I got close to the window, I was rocking her so hard that she flew out of the wrap, flew through the window, and fell into a vegetable plot. Thank goodness J was all right, but my wife was outraged to find out about this when she returned and never again entrusted me with babysitting responsibilities.

One thing still breaks my heart as far as the children are concerned: they constantly asked me to give them a ride around for fun, but I could never take them out for a drive due to a regulation directly passed down from Kim Il-sung, who prohibited using public vehicles for private purposes. If someone found out that I was driving my children to school in my vehicle assigned for work, it would serve as a good enough reason to make me lose my job. One time a vice-premier gave his grandson a ride to kindergarten in his work vehicle and was promptly fired to set an example for others. Nobody dared to challenge Kim Il-sung’s directions, but the children, simply being children, kept asking for a ride that I was never able to provide.

When my daughter J entered kindergarten, sometimes she brought home candies she wanted to eat at home. These North Korean–made candies were so rough as to make one’s tongue bleed. But J savored the goodies and put them in front of Kim Il-sung’s and Kim Jong-il’s portraits hanging on the wall before she touched any. The rough candies were a great treasure of hers, and she kept them in a secret place. But one day the entire household turned into a pandemonium when she found out that some candies were missing. She immediately accused her brother of stealing. B defiantly denied the charge, but they started fighting like cats and dogs until my wife finally had to yell at J to bring the bag of candies. When she did, my wife noticed that the plastic bag was torn by mice, as she could see obvious teeth marks of the sly little creatures. The missing candies never returned, but at least B could prove his innocence. After this incident, I decided to buy my daughter a large sack of Chinese candies for ten dollars at a foreign currency store. In these stores, privileged people who had access to foreign currency could purchase foreign goods and North Korean souvenirs, such as ceramics and folk crafts. However, North Koreans could not use foreign currency in these stores; instead they used something called “money exchanged from foreign currency,” which was like a store coupon with a currency value written on it. Since it was a rule for any North Korean to deposit foreign currency within twenty-four hours of possession, I used the “money exchanged from foreign currency” to pay for the candies. The quality was not much better than the domestic ones, but J was beaming with joy.

“Dear daughter, you should bow to me like you do to our leaders whenever you receive candies,” I said, half joking, when I saw her happy face.

Her expression suddenly changed and she told me, looking straight into my eyes without any hesitation, “My teacher taught us we need not bow to our real fathers.”

When I heard this, instead of feeling upset, I was impressed by how well educated she was to uphold our great leaders as her true fathers.

Immediately after, she started digging into the wonderful sack of candies, and I was afraid that she might ruin her teeth. So I allowed her to eat only five a day, but one day I discovered that she had had twenty. When I asked her firmly why she’d broken the rule, she bashfully replied: “Daddy, I haven’t tried all the flavors yet, and I was getting really curious.”

At that point, I simply could not argue with the little eloquent talker.

As I worked in the trading division within the military, oftentimes when the children came back from school, they would deliver messages from their teachers requesting all sorts of favors. Sometimes they would send me letters requesting material support; at other times, they would verbally send their request through my kids.

“Daddy, my teacher asked me today if you could get her some cigarettes,” J would tell me when she saw me walking into the house.

“Does your teacher smoke?”

“No, but the kindergarten is working on a construction project, you know. They told me that you would understand.”

J was repeating what her teacher told her word for word. Surely the teachers would barter the cigarettes to obtain whatever they needed for the construction project in order to make ends meet.

“How many packs does she need?” I asked.

“I don’t know, but we need to give them only a couple of packs each time, because they always ask for more and more.”

This time, J was repeating what I’d said to her the last time she’d requested cigarettes on behalf of her teacher. The teachers’ requests for material support kept growing as the economic situation in North Korea worsened in the early 1990s. I wanted to do whatever I could, but I soon reached the point when I could not meet their demands anymore. Irritated with good reason, I took time to visit the director of the school and protested.

“Comrade Director, this school must be suffering bad management. How could you possibly request so much from a parent who is mainly concerned about their children? All you seem to care about is what you can get out of their parents, not educating the children properly!” I unleashed my temper and saw the director’s lean face grow pale.

“Lieutenant Colonel, I am very sorry to have bothered you. But you might know as well that our school is no longer receiving an annual budget from the government. We have to rely on ourselves to run this place and take care of your children.”

The director profusely apologized, but frankly speaking, there was not a single reason for her to do so. As she had said, it would have been impossible to run the school without extracting resources from parents because the government practically stopped providing necessary funding. The frustration I felt was compounded by the somber reality of our deeply troubled economy. The basic needs of everyday life—food, clothing, education—were getting difficult to obtain. There was nothing I could do about it. Nor was there anything the director of the school could do. We could only be resourceful and patiently hope for better.

Loyalty Funds

It would not surprise any North Korean to hear that an economically troubled socialist country is the place where the most excessive forms of capitalism flourish. As far as I can remember, this certainly was true as early as the late 1970s. At that time, as a token of extreme loyalty to the Great Leader, the Chief of the People’s Armed Forces, General Oh, submitted a proposal to Kim Il-sung that each military unit set up a department to earn foreign currency to provide for its own expenses, in order to relieve the Great Leader’s worries about nationwide economic hardship. Soon after the proposal had been accepted, the Great Leader instructed that each military unit work toward realizing General Oh’s excellent plan. Subsequently, the People’s Armed Forces (

Inmin muryeokbu

), the National Security Agency,

5

and the Social Safety Agency (

Sahoe anjeonbu

),

6

three mighty organizations in the North Korean military and security listed in the order of their influence and power, each saw the establishment of a foreign currency–earning department within their organization. Each department ran trading companies; the one I worked for in the NSA was called West Sea Asahi Trading Company. In the late 1980s our company’s goal was to generate a half-million-dollar profit annually by exporting lucrative items, such as mushrooms, medicinal herbs, seafood, and the like. However, Kim sent an instruction to raise the goal to a million dollars in the early 1990s and thereby weed out weaker companies, as so many workplaces wanted to run such companies for profit. Our company remained in operation, as it was never a problem to meet the goal of generating the designated million dollars.

As a NSA military officer earning foreign currency for the party, I always had access to various goods and had no difficulty supporting my family. In a semiprivate firm where generating profit was the primary objective, every officer wanted to stand out. The foreign currency–earning department was a small capitalist island in this highly controlled North Korean state—an exceptionally competitive environment within a gigantic system loaded with lethargic and corrupt workers. Competition was rough. Unlike many incompetent compatriots, everyone in the company worked around the clock. In the West Sea Asahi Trading Company, there were around 30 workers, all with the rank of colonel or lieutenant colonel, who were supervised by a one-star general. Although this looks like a very tiny fraction of the entire society, a much larger network of North Korean people would be involved in foreign currency–earning activities. In every province, the West Sea Asahi Trading Company had a branch headed by lieutenant colonels, who would in turn command 300 to 500 local workers and staff members. These local workers would work with other local farmers and workers who comprised the lowest stratum of this state-led capitalist food chain.

Everyone worked so hard, as if they were on the battlefield, in order to generate surplus over the one-million-dollar minimum annual quota. But since these companies worked under the full protection of the Great Leader and the party and exercised a monopoly over lucrative export items, earning a million dollars was never a challenge. Quite the contrary, each trading company would end up with a surplus, which eventually filled the pockets of the people in leadership positions. If a company worker could contribute to accumulating wealth for his superior, then he would be favored and looked after. This way, a harsh competition among subordinates, akin to the survival of the fittest, was set up to accumulate private wealth for their superiors. Based on my personal experience working for the West Sea Asahi Trading Company, I can say that the total profit was split between the Korean Workers’ Party and the trading company on roughly a 7 to 3 ratio, which means that on the average, the annual surplus was well over $400,000. This profit, which did not get absorbed by the party, ended up being used to bribe higher-ups who would facilitate the operation of the trading company, as a kind of investment for future business. Whatever surplus funds were not used as bribes ended up in company heads’ Swiss bank accounts or other secret places.

For the West Sea Asahi Trading Company, the main export item was seafood, but exporting mushrooms to Japan was another extremely lucrative business, which was monopolized by Kim Jong-il’s office as one of the main resources to earn foreign currency. Our company was brought in to facilitate the operation. Mushrooms of the highest quality could cost as much as $360,000 a ton. However, they had to be exported soon after picking in order to guarantee freshness. This could be challenging. One time there was a group of mushroom farmers who demanded higher food rations from the government in exchange for their crop. In protest, they refused to hand over the mushrooms that were supposed to be shipped to Japan the same day. I knew too well that these farmers were getting only a meager ration for the lucrative produce. They would have fallen unconscious had they known how much foreign currency their crops were bringing in and how absurdly minuscule their portion was in the entire scheme of profit sharing. But since it was my job to make sure the products were delivered to Japan on time, I had to come up with some sort of emergency plan. The company was counting every second to ship the goods, and it would have been counterproductive and even dangerous to directly meet the anger of these farmers. So I offered them an abundant amount of rice wine as a way of opening up discussion, but my plan was to make them drunk. I kept offering drinks while only pretending to drink with them, under the pretense of making peace. The farmers, who were not used to such treats, took advantage of the occasion. When the last farmer was about to pass out, I ordered my subordinates to load the truck with boxes of mushrooms. We had to drive all night to Pyongyang airport without a break to meet the scheduled time for shipment. The final dramatic touch to this emergency plan was to disguise our truck as a funeral car. This was a good idea, as we saved some time at inspection points.