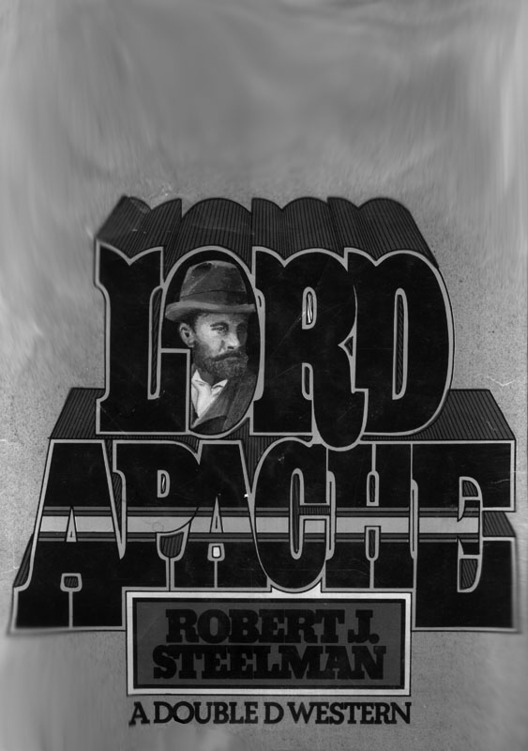

Lord Apache

by Robert J. Steelman

Scanned and Proofed by RyokoWerx

At ten in the morning the Fahrenheit thermometer stood at one hundred degrees. September sun glittered on the harsh mirror of the desert. Mirages shimmered around the pack train. Even the mules were deceived, straying from the rutted wagon road to reach the beckoning lakes, tree-rimmed islands. But there were no lakes, no islands, not even human beings; the caravan might have been traveling through a lunar landscape.

It was three days since they had left the village of Phoenix, at the junction of the Salt and Gila rivers. Under the shade of his Bombay

topi

, Jack Drumm's wind-reddened eyes stared at his man Eggleston.

"Are you all right, Eggie?"

The valet smiled wanly, holding the umbrella over his bald head. Incongruous in the heat, he wore a wilted collar and nankeen coat in spite of his master's kindly permission to remove them.

"I am well, Mr. Jack," he murmured, "except for a slight ringing in my ears, and a touch of giddiness."

Drumm handed him a canteen. "In Marrakesh, in Morocco, you remember they warned us to beware of the desiccating effect of the desert. This Arizona Territory heat is certainly worse." The plump young man scanned the horizon through a brassbound telescope, his straw-colored mustache twitching in distaste. "A sunbaked inferno! I don't know what possessed me to route my Grand Tour through this wasteland! We should have taken the steam cars direct from San Francisco to New York, and thus home to Hampshire."

Eggleston handed back the canteen. "I am refreshed now, sir. Please do not worry about my welfare! I am a coper, as you well know, and will handle anything that comes my way, even the very fires of hell!"

Drumm clapped him on the back. "Spoken like a true Briton, Eggie! I am proud of you. Anyway, this is certainly the hottest part of the day, and it can only become cooler." He pointed to a tracery of green in the distance. "That must be the Agua Fria River. According to my map, it is a tributary of the Salt. After we negotiate the pass ahead, the river is only a few miles farther. We will camp along its banks tonight."

In spite of Drumm's prediction, the day grew hotter. The playa, as the early Spanish explorers named the desert, sweltered in the sun as the heavily laden train toiled toward the pass. Whorls of dust arose, swirling like dancers across the plain. The wind blew with the hot breath of a forge. Far to the north, beyond the new territorial capital of Prescott, the Aquarius Mountains were a jagged brown scar on the horizon. The Mazatzal range, to the east beyond the meandering Agua Fria, loomed high above the desert, a few trees greening its high ridges. For a moment there was a wink of light from its wooded slopes, perhaps a ray of sunlight reflected from snow-water; then it was gone. On Mazatzal, Drumm reflected, it would be cooler. According to his map the peak was over nine thousand feet in elevation. But on the playa there was no relief. Like insects trapped on a gigantic baking dish the party inched northward toward the river.

Late in the afternoon they turned aside from the deserted road to rest in the shade of a scraggly bush. From his

Traveler's Guide to the Far West

Drumm identified it as the desert ironwood. He was preparing to sit beneath it with his pad to make a quick sketch when Eggleston cried out in alarm:

"Careful, sir! Don't sit there!"

Drumm watched the dusty gray coils as the snake writhed from its lair, tail buzzing, undulating body making diagonal marks in the sand.

"

Crotalus cerastes

," he murmured. "What they call the sidewinder, Eggie. Very common out here! Good Lord, look at it travel, will you?"

While Eggleston brewed tea over a fire of mesquite twigs, his master took out his sextant and sighted the elevation of the sun. "We are very near my dead-reckoning position," he announced. "Perhaps another two days to the town of Prescott." He consulted the map, and pointed. "Over there is a small settlement called Weaver's Ranch. Can you imagine, Eggie—human beings actually

choosing

to live in this desolation?"

The valet fingered a strip of rawhide dangling from the branches of the ironwood tree. "I wonder what this is, Mr. Jack."

Together they examined it, a leather thong knotted along its length in a way that seemed to indicate a message.

"This too," Eggleston muttered apprehensively, pointing to cabalistic figures freshly scratched on a boulder. "And over there also—a pile of rounded stones."

"Well, they are manmade, that is sure," Drumm said. "No desert tortoise or Gila monster is likely to have manufactured them."

Eggleston swallowed. "Perhaps—Indians?"

Drumm shrugged. "If there are Indians about, they are probably Pimas, or Papagos; docile farmers, as they informed us in Yuma, who do not molest travelers. The Apaches, of course, are warlike, but I understand General Crook has pacified them. They are living peacefully on the government's reservations."

The valet was still doubtful. He pointed to the tracks in the wagon road. "None of those traces appear to be very new. Where, then, are the wagons?"

Drumm put away his navigation instruments and took the cup of tea and the biscuit Eggleston offered.

"What do you mean?"

"In Phoenix, old Mr. Coogan, who sold us our mules, said there would be frequent wagon trains carrying goods to Prescott and Fort Whipple and the Army camps—stagecoaches, also, on regular routes to the north. But we have not seen a vehicle since we left Phoenix."

Drumm rubbed a sunburned nose. "That is so," he admitted. "Something

is

odd about the situation!"

Together they squatted in the scanty shade of the ironwood tree, feeling the immensity of the deserted land, their smallness in it. Unlike the beneficent orb so welcome in Hampshire after a damp and chill winter, the sun here was brassy and impersonal. Here, also, the wind blew steadily; dust devils swirled, the horizon stretched to infinity.

Drumm cleared his throat. "I am quite sure, Eggie," he said, "that there is no danger to us."

Still, the scrap of leather with its ominous knotted message danced in the wind, the scratches on the boulder confronted them with an arcane message, the geometrical pattern of stones somehow menacing.

"Besides," Drumm added, "we are well armed." Taking the Belgian fowling piece from his saddle, he examined the load. "In any case, there is nothing to fear from the tribesmen who inhabit this area. They are poor ignorant brutes, like the fellahin we saw last year in Egypt. They would probably break and run at the first volley from modern weapons."

They got again into the saddle and advanced toward the pass. Anxious to reach the Agua Fria, Jack Drumm rode along the column, whipping up the sullen mules. The valet galloped after a stray and whacked it soundly on the rump.

"Ho, there, sirrah—back on the road! Mr. Jack, was there ever anything so stubborn as a mule?"

"I fear," Jack Drumm said, "that my own stubbornness is evident also, Eggie. I know you did not wish to embark on this desert journey. Instead, when we landed at San Francisco from Japan, you preferred to go directly east. Well, I am now of the same mind. I understand there is a military telegraph at Fort Whipple, near Prescott. When we reach there I will arrange to have a cable forwarded to my brother Andrew at Clarendon Hall, advising him I have abandoned this foolish journey through the wilds of America, and plan to return home directly without seeing the Grand Canyon of the Colorado or the famous Painted Desert. Surely the Grand Tour has been grand enough without this bleak and inhospitable wasteland!"

The Prescott wagon road soon pinched in to a narrow canyon, walls steep and abrupt. At the entrance they looked at each other with misgiving.

"Hallo!" Drumm called, cupping his hands.

His shout died away in the depths of the canyon, to return a moment later in an eerie diminishing echo. The air was hot, stifling, somehow taut.

"Well," Drumm shrugged, "there is no other way to go but through the canyon!"

They herded the mules before them through the cactus-studded defile. The beasts plodded unwillingly, heads down and ears laid back, braying protests as they slipped and scrambled on the rocks. Drumm kept the fowling piece across his lap, ready for action, and Eggleston gripped his pistol tightly. As they rode, both watched the rocky heights; it was patent that hostile Indians could ambush them from above. Even if the Pimas and Papagos were amicable, and the Apaches confined to reservations, the pair was not too far from the country of the Navahos.

A few hundred yards into the canyon Eggleston raised a hand. "

Hsst

, Mr. Jack! Did you hear that?"

When they paused, the weary mules paused also.

"Hear what, Eggie?"

Borne faintly on the wind, there came to them the far-off rattle of hoofs and a shrill neigh. The mules pricked up their ears. Old Mr. Coogan said the mules could smell Indians. If they acted uneasy, as they were now certainly doing, hostile tribesmen might be about. One animal rolled eyes whitely and started to back down the canyon.

"The Indians," Drumm said in a tight voice, "may be friendly after all, Eggie. But be ready to fire when I give the command. First, however, I will attempt to 'palaver' with them, as they say on the frontier."

Tense and expectant, they waited. Above, a hawk wheeled on a rising current of air. The bird could see whatever peril awaited them, but they could only watch and listen. The clatter of hoofs grew louder, and a curl of dust rose from the cleft of the canyon above them. Someone shouted, a cry that might have been a war whoop. Jack Drumm paled, but spoke firmly.

"Steady, Eggie! Remember the hollow square at Lucknow!"

Suddenly a banner wavered above the rocks, high on a staff. A moment later a trooper cantered down toward them. The rest of the column picked its way down the narrow defile—lank, angular men, in corduroy and buckskin breeches and sweat-soaked flannel shirts.

"Thank God!" Eggleston breathed a heartfelt relief. "Look, Mr. Jack, it is the cavalry—the U. S. Army!"

To Drumm, familiar with the Royal Horse Guards in their blue tunics, white helmets with horsehair plumes, and polished steel cuirasses, the oncoming soldiers were a nondescript lot with little discipline and even poorer appearance. The lieutenant, a young man in a felt hat, sporting a ragged black beard, was slouched in the saddle as if it were an easy chair.

"Dunaway," he drawled, extending a hand to Jack Drumm. "B Company, Sixth Cavalry, from Fort Whipple." He jerked his head toward the ridge above them. "Saw you from on top. Had our eye on you for a long ways. See any hostile sign on the playa?"

Drumm took off the sun helmet and wiped the sweatband with a fresh handkerchief.

"Any what?"

Dunaway was impatient. "Hostile sign! Indians! Apaches!"

"Actually, no." Drumm put on the topi again. "No Indians, that is. But there

were

peculiar things in the road. Knotted rawhide strings, piles of rocks, hieroglyphics scratched on boulders."

Dunaway nodded. "Apache messages; that's the way they keep in touch with each other."

"But I thought—"

"All hell broke loose two days ago!" The lieutenant slapped the battered hat against his thigh; a cloud of dust arose. "Agustín burned Weaver's Ranch to the ground—killed Weaver's boy Sam and some Mexicans, set fire to the hay, butchered a steer, and ran off the stock they couldn't eat. It's up to us to put him back in the bottle and ram home the cork."

"Agustín? Who is Agustín?"

Dunaway gave Jack Drumm a pitying look. "You never heard of him?"

"No."

"Agustín is just chief of the Tonto Apaches, that's all! Took his braves and ran away from the Verde River reservation after a fuss with the Indian agent about bad beef his people were issued. You fellows were probably on the road when it happened, and didn't get the word. But everyone between Phoenix and Prescott knows! We've alerted all posts by telegraph. Things have come to a standstill—nothing moving on the wagon road, everyone scared. Territorial Legislature even wants General Crook removed unless we cut Agustín's trail mighty quick and dehorn him."

Eggleston looked puzzled, turning to his master for enlightenment.

"I think," Jack Drumm said, "it is meant that the cavalry must find Mr. Agustín quickly, and—well, render him harmless, one might say."

Dunaway regarded him with amusement. "I guess you might say that." He grinned, fondling his beard. "You're English, aren't you?"

"John Peter Christian Drumm, from Clarendon Hall, in Hampshire. My father is—was—Lord Fifield, the ambassador. Before he died, he insisted I see something of the world. But I must admit I was not prepared for Arizona."

Dunaway blew his nose with a handkerchief of the kind called a bandanna and stuffed it into a hip pocket. "Few folks are," he said, condescension in his voice. He watched his men milling about Drumm's pack train, exclaiming at the quantity and variety of equipment. "Look!" a brigandish-looking corporal cried. "God damn me, if it ain't a commode—a—a mechanical slop jar!"