Lost in the Cosmos: The Last Self-Help Book (9 page)

Read Lost in the Cosmos: The Last Self-Help Book Online

Authors: Walker Percy

Tags: #Humor, #Essays, #Semiotics

Thus, the rightful legatee of the greatest of fortunes, the cultural heritage of the entire Western World, its art, science, technology, literature, philosophy, religion, becomes a second-class consumer of these wares and as such disenfranchises itself and sits in the ashes like Cinderella yielding up ownership of its own dwelling to the true princes of the age, the experts.

They

know about science,

they

know about medicine,

they

know about government,

they

know about my needs,

they

know about everything in the Cosmos, even me.

They

know why I am fat and

they

know secrets of my soul which not even I know. There is an expert for everything that ails me, a doctor of my depression, a seer of my sadness.

(h)

Because modern life is enough to depress anybody? Any person, man, woman, or child, who is not depressed by the nuclear arms race, by the modern city, by family life in the exurb, suburb, apartment, villa, and later in a retirement home, is himself deranged.

(

CHECK ONE OR MORE

)

Question

(II): Why do so many teenagers, and younger people, turn to drugs?

(a)

Because of peer-group pressure, failure of communication, psychological dysfunction, rebellion against parents, and decline of religious values.

(b)

Because life is difficult, boring, disappointing, and unhappy, and drugs make you feel good.

(

CHECK ONE

)

Thought Experiment:

A new cure for depression:

The only cure for depression is suicide.

This is not meant as a bad joke but as the serious proposal of suicide as a valid option. Unless the option is entertained seriously, its therapeutic value is lost. No threat is credible unless the threatener means it.

This treatment of depression requires a reversal of the usual therapeutic rationale. The therapeutic rationale, which has never been questioned, is that depression is a symptom. A symptom implies an illness; there is something wrong with you. An illness should be treated.

Suppose you are depressed. You may be mildly or seriously depressed, clinically depressed, or suicidal. What do you usually do? Or what does one do with you? Do nothing or something. If something, what is done is always based on the premise that something is wrong with you and therefore it should be remedied. You are treated. You apply to friend, counselor, physician, minister, group. You take a trip, take anti-depressant drugs, change jobs, change wife or husband or “sexual partner.”

Now, call into question the unspoken assumption: something is wrong with you. Like Copernicus and Einstein, turn the universe upside down and begin with a new assumption.

Assume that you are quite right. You are depressed because you have every reason to be depressed. No member of the other two million species which inhabit the earth—and who are luckily exempt from depression—would fail to be depressed if it lived the life you lead. You live in a deranged age—more deranged than usual, because despite great scientific and technological advances, man has not the faintest idea of who he is or what he is doing.

Begin with the reverse hypothesis, like Copernicus and Einstein. You are depressed because you should be. You are entitled to your depression. In fact, you’d be deranged if you were not depressed. Consider the only adults who are never depressed: chuckleheads, California surfers, and fundamentalist Christians who believe they have had a personal encounter with Jesus and are saved for once and all. Would you trade your depression to become any of these?

Now consider, not the usual therapeutic approach, but a more ancient and honorable alternative, the Roman option. I do not care for life in this deranged world, it is not an honorable way to live; therefore, like Cato, I take my leave. Or, as Ivan said to God in

The Brothers Karamazov:

If you exist, I respectfully return my ticket.

Now notice that as soon as suicide is taken as a serious alternative, a curious thing happens.

To be or not to be

becomes a true choice, where before you were stuck with

to be.

Your only choice was how

to be

least painfully, either by counseling, narcotizing, boozing, groupizing, womanizing, man-hopping, or changing your sexual preference.

If you are serious about the choice, certain consequences follow. Consider the alternatives. Suppose you elect suicide. Very well. You exit. Then what? What happens after you exit? Nothing much. Very little, indeed. After a ripple or two, the water closes over your head as if you had never existed. You are not indispensable, after all. You are not even a black hole in the Cosmos. All that stress and anxiety was for nothing. Your fellow townsmen will have something to talk about for a few days. Your neighbors will profess shock and enjoy it. One or two might miss you, perhaps your family, who will also resent the disgrace. Your creditors will resent the inconvenience. Your lawyers will be pleased. Your psychiatrist will be displeased. The priest or minister or rabbi will say a few words over you and down you will go on the green tapes and that’s the end of you. In a surprisingly short time, everyone is back in the rut of his own self as if you had never existed.

Now, in the light of this alternative, consider the other alternative. You can elect suicide, but you decide not to. What happens? All at once, you are dispensed. Why not live, instead of dying? You are free to do so. You are like a prisoner released from the cell of his life. You notice that the door to the cell is ajar and that the sun is shining outside. Why not take a walk down the street? Where you might have been dead, you are alive. The sun is shining.

Suddenly you feel like a castaway on an island. You can’t believe your good fortune. You feel for broken bones. You are in one piece, sole survivor of a foundered ship whose captain and crew had worried themselves into a fatal funk. And here you are, cast up on a beach and taken in by islanders who, it turns out, are themselves worried sick—over what? Over status, saving face, self-esteem, national rivalries, boredom, anxiety, depression from which they seek relief mainly in wars and the natural catastrophes which regularly overtake their neighbors.

And you, an ex-suicide, lying on the beach? In what way have you been freed by the serious entertainment of your hypothetical suicide? Are you not free for the first time in your life to consider the folly of man, the most absurd of all the species, and to contemplate the comic mystery of your own existence? And even to consider which is the more absurd state of affairs, the manifest absurdity of your predicament: lost in the Cosmos and no news of how you got into such a fix or how to get out—or the even more preposterous eventuality that news did come from the God of the Cosmos, who took pity on your ridiculous plight and entered the space and time of your insignificant planet to tell you something.

The consequences of entertainable suicide? Lying on the beach, you are free for the first time in your life to pick up a coquina and look at it. You are even free to go home and, like the man from Chicago, dance with your wife.

The difference between a non-suicide and an ex-suicide leaving the house for work, at eight o’clock on an ordinary morning:

The non-suicide is a little traveling suck of care, sucking care with him from the past and being sucked toward care in the future. His breath is high in his chest.

The ex-suicide opens his front door, sits down on the steps, and laughs. Since he has the option of being dead, he has nothing to lose by being alive. It is good to be alive. He goes to work because he doesn’t have to.

How the Self can be Poor though Rich

MOTHER TERESA OF CALCUTTA

recently remarked about some affluent Westerners she had met—including Americans, Europeans, capitalists, Marxists—that they seemed to her sad and poor, poorer even than the Calcutta poor, the poorest of the poor, to whom she ministered.

Question:

What kind of impoverishment can be attributed to the denizens of Western technological societies in view of the obvious wealth of such societies in such categories as food, shelter, goods and services, education, technology, and cultural institutions?

(a)

There is no such sadness and impoverishment. Mother Teresa makes such a charge because Western societies, with their increasing acceptance of contraceptive birth control and abortion, offend her Roman Catholic religious beliefs.

(b)

There is, in fact, such a sadness and an impoverishment, due at least in part to a loss of respect for human life as evidenced not only by the acceptance of abortion but by mounting child abuse, euthanasia, and indifference to human suffering. Recent studies have shown, however, that Westerners, that is, Europeans and Americans, own more pets than ever and spend more money on pet food and veterinarians than the food costs of the entire Third World.

(c)

There is such a sadness and impoverishment because in an affluent society, where there is a surfeit of goods and services, there is a corresponding devaluation. Whereas the poor peoples of the Third World, despite or because of their material deprivation, appreciate the simple things in life. Small is beautiful, the best things in life are free, etc.

(d)

Because the poor in heart are blessed, i.e., receptive to the Gospel, whereas the rich may gain the whole world but lose their souls.

(e) Because Western society is an ethic of power and manipulation and self-aggrandizement at the expense of the values of community, love, innocence, simplicity, values encountered both in childhood and in non-aggressive societies (e.g., the Eskimo). As Ashley Montagu says, adulthood in the Western world is a deteriorated and impoverished childhood.

(f)

Because Western society is itself a wasteland, its values decayed, its community fragmented, its morals corrupted, its cities in ruins. In the face of the deracination of Western culture, all talk of self-enrichment through this or that psychological technique is cosmetic, like rearranging the deck chairs of the

Titanic.

The Moral Majority is right. The only thing that can save us is a return to old-time religion, a revival of Christian Fundamentalism.

(g)

None of the above. All arguments between the traditional scientific view of man as organism, a locus of needs and drives, and a Christian view of man as a spiritual being not only are unresolvable at the present level of discourse but are also profoundly boring—no small contributor indeed to the dreariness of Western society in general. The so-called détentes and reconciliations between “Science” and “Religion” are even more boring. What is more boring than hearing Heisenberg’s uncertainty relations enlisted in support of the freedom of the will? The traditional scientific model of man is clearly inadequate, for a man can go to heroic lengths to identify and satisfy his needs and end by being more miserable than a Calcuttan. As for the present religious view of man, it begs its own question, the question of God’s existence, which means that it is not only useless to the unbeliever but dispiriting. The latter is more depressed than ever at hearing the goods news of Christianity. From the scientific view at least, a new model of man is needed, something other than man conceived as a locus of bio-psycho-sociological needs and drives.

Such an anthropological model might be provided by semiotics, that is, the study of man as the sign-using creature and, specifically, the study of the self and consciousness as derivatives of the sign-function.

Thought Experiment:

If Mother Teresa is right and there exists in modern technological societies a paradoxical impoverishment in the midst of plenty, in the face of what is by traditional objective scientific criteria the most extensive effort in all of history to identify and satisfy man’s biological, psychological, sociological, and cultural needs, consider a different model. Consider a more radical model than the conventional psycho-biological model, a semiotic model which allows one to explore the self in its nature and origins and to discover criteria for its impoverishment and wealth.

The following section, an intermezzo of some forty pages, can be skipped without fatal consequences. It is not technical but it is theoretical—i.e., it attempts an elementary semiotical grounding of the theory of self taken for granted in these pages. As such, it will be unsatisfactory to many readers. It will irritate many lay readers by appearing to be too technical—what does he care about semiotics? It will irritate many professional semioticists by not being technical enough—and for focusing on one dimension of semiotics which semioticists, for whatever reason, are not accustomed to regard as a proper subject of inquiry, i.e., not texts and other coded sign utterances but the self which produces texts or hears sign utterances.

A Short History of the Cosmos with Emphasis on the Nature and Origin of the Self, plus a Semiotic Model for Computing Impoverishment in the Midst of Plenty, or Why it is Possible to Feel Bad in a Good Environment and Good in a Bad Environment

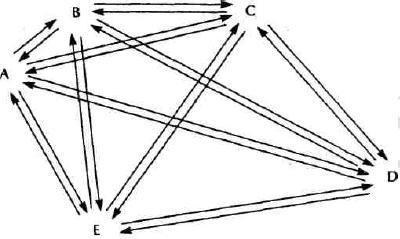

From the beginning and for most of the fifteen billion years of the life of the Cosmos, there was only one kind of event. It was particles hitting particles, chemical reactions, energy exchanges, gravity attractions between masses, field forces, and so on. As different as such events are, they can all be understood as an interaction between two or more entities: A↔B. Even a system as inconceivably vast as the Cosmos itself can be understood as such an interaction: