Lost Worlds (19 page)

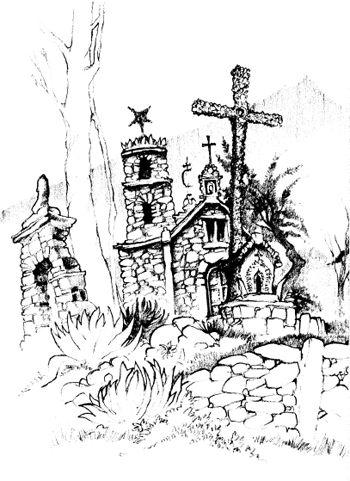

I shivered in the swirling mists. The place had far more impact than all those realistic blood-and gore-stained Christ figures I’d seen in Venezuelan Catholic churches. I could sense the agony and the horror of the artist himself expressed in these primitive figures. Juan must have felt those nails through his own hands.

Then something very odd began to happen. As I stared at the tortured faces and the hands of Christ outstretched in agony, the mists began to clear and sunlight touched the crosses and piled boulders. Within a couple of minutes the hill was bathed in a brilliant afternoon light; the carved wooden bodies turned from a dead gray to a rich resin bronze. The place no longer seemed threatening and full of misery. There was a sense of new life now, new vigor in the figures—a resurrection in sunlight!

The cynical, agnostic part of my brain rebelled at such thoughts. I could sense it chuckling at the naïveté of this often confused individual, moved almost to tears by a trick of fickle microclimate—the sudden presence of warmth and light in the midst of a chilly cloudbound afternoon. All the tangled thoughts of my night under the stars came rolling back, trying to reduce the impact of the moment to the insignificance of over-emotiveness and a passing hysteria.

But as I left the hill and the little stone church, something remained with me…

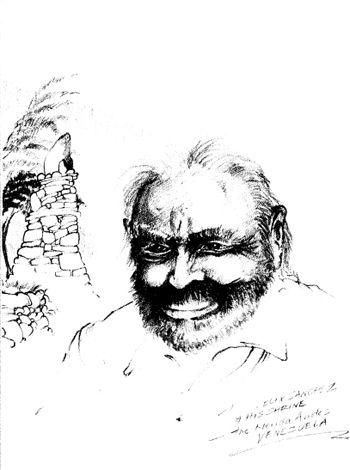

The days eased by in El Tisure and I spent time with Juan sitting quietly in his sunlit corral, sometimes talking, sometimes silent.

I remember one strange and moving incident. During one of our long silences in the shade of the corral wall, I fell asleep and dreamed. The dream ended as abruptly as it had begun. I found I was crying. Big, hot tears were squeezing between my closed eyes and rolling down my cheeks.

I opened my eyes and saw Juan looking at me and smiling. “I’m sorry. I had a dream.”

“Yes. It was a very good dream,” Juan said.

He didn’t ask me. He told me.

“Yes it was. It reminded me of something—somebody—I keep forgetting.”

“Yes.”

“My father,” I said. Those damned tears kept on rolling.

“Yes.”

“He was a good man. Like you. He cared about so many things…”

Juan nodded as if he knew more than I wanted to tell him.

I tried to laugh. “Wow—that was something. I haven’t thought about him for a long time—far too long.”

Juan smiled and, once again, he reminded me so much of the father I loved—the kind, vulnerable, wise man behind the stern-father mask.

“He was a good man,” Juan said.

“Yes he was—how do you know?”

He laughed quietly as if the answer was so obvious it hardly needed saying: “Because you are his son.”

Then he leaned over, squeezed my hand and repeated the phrase—“because you are his son.”

Looking back I wish I could have learned more from the man but as he said in one of his indirect responses to yet another of my questions—“You can only learn what you already know. When you know all that you have always known, the learning is done.”

I often think of his soft laughter and of that hidden valley way back in the Venezuelan Andes. Maybe one day, when all our travelings are done, Anne and I will find our own El Tisure, our own timeless place of focus and freedom. If we do, we’ll take something of Juan Felix Sanchez with us—his smile, and that shard of stone from his little shrine in those remote mountains.

I had decided to take a couple of weeks off from world wandering and adventuring and fly down to Antigua for a little laid-back lollygagging. But Antigua was beginning to pall.

Now, don’t get me wrong. I’ve got nothing against Antigua. In fact, I have dear friends who live there and who took great pains to show me the delights of their Caribbean island, including visits to more lovely beaches than I really wanted to see. “One for every day of the year,” they boasted. After a fourth day of beach-hopping I believed them.

Of course it wasn’t all beaches. We strolled the old waterfront streets of the capital Saint Johns, visited the teeming Sunday market, ate delicious island concoctions at palm-shaded restaurants, and admired the island’s exclusive and ultra-expensive resort enclaves. We also spent a frenzied Sunday afternoon of reggae and dancing on the windy hilltop of Shirley Heights overlooking the historic Nelson’s Dockyard and the blue-hazed outlines of St. Kitts-Nevis and Montserrat out in the turquoise ocean. I watched a cricket match featuring Antigua’s most beloved citizen, Viv Richards, played the ancient African game of warri with the locals, became embroiled in furious rum-laced debates with the editor of a radical island newspaper, and visited with a “family” of agrarian Rastas living a marijuana-laced life in a secluded valley, well away from the tourist beaches.

But after a week or so of all this activity I was ready for something different, something slower-paced, something that needed a backpack and little else.

Then someone whispered to me about tiny Barbuda.

I hadn’t realized that Antigua had a sister-island about twenty-five miles to the north. (More of a stepsister, actually, almost ignored by her large and well-endowed sibling.) A place with hardly more than a thousand residents—untouched, unspoiled, unincorporated into the maelstrom of modern-day enigmas that impact Antigua. A Robinson Crusoe paradise where I might discover what the Caribbean looked like and felt like before the twentieth century came carousing in, cluttering quiet coves with condos, releasing plagues of package-tour promoters and Fantasy Island resort developers. A little lost world, here in the heart of the Caribbean. Something I’d not expected.

It was so good to be on the ocean in a small boat bouncing across the choppy waves under a cloudless blue sky. I was the only passenger and Sam “Frigatebird” Jackson, the skipper, gave me snippets of Barbuda history during our three-hour journey.

“You won’t think it once y’see it—it’s only a tiny place, ’bout twenty miles tip to toe—but it’s got a history long as a frigate bird’s wings.”

“I meant to ask you, Sam—why do they call you Frigatebird?”

“Ah—you jus’ wait ’n’ see. I’m not going to be tellin’ you everythin’ before we gets there. This ain’t no ordinary place an’ you got to take it in gradual—like drinkin’ strong punch.”

I liked the man already. He must have been in his sixties, with his crinkled face a dark rich mahogany color and a substantial belly that overhung his bleached jeans and strained every stitch of his pale blue T-shirt.

“So—’bout this place’s history. They all tried to tame it like all the other islands—the British and the French. Tried to plant their plantations ’n ’all that in the 1600s. But it wouldn’t take. Couldn’t get it goin’ right ’cause of them Carib tribes. They were real mighty men, those Caribs. Didn’t like people comin’ in and claiming their land—even though tha’s what they done to the people that lived here before they came. Got rid of them pretty fast—the Caribs just came in and took what they wanted. Sometimes they stayed. Sometimes they moved on. But the Europeans, they always came back and ’round ’bout 1680—after King Charles II leased the island to this family called Codrington for ’one fatted sheep a year’—they attacked with six war canoes and chopped up most of Codrington’s men and messed up all the plantations.”

“So that’s why the island is so untouched today?”

“Hey—wait a minute. We not started yet. There’s plenty more. Those British settlers don’t give up so easy. Few years later they were back again and the Codringtons built themselves a castle, this time on a hill—th’ only hill Barbuda’s got—and started breedin’ slaves for their Antigua sugar fields. You heard of them slave stock farms before, ain’t you?”

I suppose I had, but it’s not a part of British colonial history that I like to dwell on, so I mumbled something incoherent and Sam continued.

“Well—then the French decided it was their turn and came in ’round 1710 and blew up the castle and took all the slaves. I tell you, these were wild days ’round this part of the Caribbean. All the stuff people get upset about now—y’know, all that government shenanigans stuff and all the fuss about too much development?—tha’s tame compared to what went on here two hundred, three hundred years ago. Even after the French got kicked out there were plagues of smallpox, then some Englishman tried to set up his own little kingdom here, then there were slave riots and problems with the Codringtons’ lease, and then came the War of Independence in the USA and the Americans stopped trading with the British West Indies and everybody was going bankrupt. I tell you, this place might look like paradise, but it was a hellhole for a hundred years or so. Then the British tried to give it away and when nobody would take it they said Antigua had to look after it and that’s the way it still is—Antigua and Barbuda—one country but two different places. Real different.”

And how right he was. This little lost world in the middle of one of the earth’s most intensively developed tourist regions is the epitome of peace and apartness. Long, low vistas of unbroken, unpeopled beaches greeted us as we sailed north through Gravenor Bay, past the ruins of an old stone martello defense tower built as a rather ineffective bastion against the French, and then up alongside the long sandbar separating Codrington Lagoon from the ocean. Over a hundred wrecks are recorded in the shoals and reefs around the island. It is a treasure hunters’ paradise (Mel Fischer has been here numerous times with his treasure-hunting expeditions) and ideal for scuba diving, except most scuba divers don’t even know the place exists.

Entering the lagoon at its northern tip near Goat Point was a tricky business and Sam was unusually silent as he nudged his small boat through the ever-changing curlicues of sand banks and channels and patches of sharp coral heads.

Mangroves rioted along the low shorelines and behind them lay a ragtag mass of palms and thick jungly undergrowth that rose to a hazy series of limestone hills known as the Highlands.

The ocean breezes had stilled and it was hot as we edged southward down the widening channel into Codrington Lagoon. There was no sign anywhere of activity. It was almost as though we’d entered our own uncharted island and had the place all to ourselves—surely an impossibility in the Caribbean. And when Sam suggested we “stop off an’ get some beer in town” my worst fears were awakened.

“Town! What town?”

“Codrington. Just a couple of miles down.”

I shouldn’t have worried. “Town” consisted of a post office, a police station, and a few pastel-shaded tin-roofed shacks hidden in the low scrub.

“That’s the town?”

“Yeah,” said Sam, “that’s all there is. But there’ll be some beer around somewhere.”

“There’s no other place on the island. Just this?”

“That’s it. There’s people living and gardening back in a ways, but there’s less than a thousand folks on Barbuda and you likely won’t see a one of them.”

Codrington seemed deserted, but Sam managed to find some beer at a friend’s house and we sat in the shade of palms overlooking the lagoon. Behind us was a riot of flowering bushes—bougainvillea, red ginger, hibiscus, frangipani.

After a while Sam said, “Y’asked me about my name—Frigatebird. You want to see why they call me that?”

“Sure.”

Half an hour later we were easing across the main lagoon toward the mangrove swamp northwest of “town.” Sam was grinning. “These birds are real beautiful.”

“What birds?”

“Jus’ hold on,” he said, “till we get ’round into the small lagoon.”

We left the open water behind us and entered a strange, silent world of thick mangroves and narrow channels bounded by reeds. It was hot now; the tradewind breezes were blocked by the dense vegetation and our T-shirts were quickly drenched once again in sweat. Sam was pointing and whispering, “You see ’em now?”

What I’d taken to be puffy white flowers among the mangrove bushes slowly became faces—lovely down-covered faces with silver-gray beaks and calm, curious eyes. Scores of them, watching us as we edged closer to the marshy shore.

“You can tell the male birds. Look for the red balloons.”

“The what?”

“The red balloons—they puff up those red pouches over their necks. Like balloons. Gets the lady birds crazy when they’re mating.”

I saw them now, among the deep green of the mangrove leaves, lots of bright red “balloons” all blown up for our benefit.

As we floated closer to the nests I expected commotion, panic, and a great flurry of wings. But nothing happened. The birds just sat there, bobbing their heads as if in greeting, and watching us with those lovely quiet eyes.

“Ain’t they something,” said Sam.

“I’ve never seen birds so tame,” I whispered.

“They got no reason to be feared. Don’t see many folks out here. And they don’t taste so good—so no one shoots ’em. They just let ’em be.”

We paused within six feet of a nesting group. I snapped away with my camera and they continued to nod appreciatively.

“Now watch this,” said Sam as he eased himself slowly out of the boat and into the shallow water. The birds turned to observe him but made no other movements as he crept slowly toward a nest, now only a yard or so away. He was making a low clicking sound that seemed to intrigue the birds. They stretched out their long necks as if to greet him.

It was magic to watch as he slowly extended an arm and began to stroke the soft white feathers of a male frigate bird’s head. Gradually his hands slid down the neck and rested on the top of the coffee-brown and black wing feathers. I watched the bird’s eyes. They were still calm—almost sleepy—as Sam stroked downward toward the tips of the wings. Then, very gently, he began to stretch out the wings themselves. They seemed to unfurl like umbrellas until, fully outstretched, they were a good six feet from tip to tip. The other birds stared, curious but unconcerned, as Sam began to lift the creature by its wings out of the down-covered nest. Its dainty white webbed feet hung unprotestingly against the broad vee of its dark tail feathers.

I was so amazed I almost forgot to photograph the process. Sam was still making those soft clicking noises and I felt an urge to giggle. I had never seen such a trusting relationship between a man and wild creature before. We get so used to the fear and timidity shown by animals and birds that we accept it as a normal state. But we’re wrong. Surely this is the true state—a state of trust and mutual confidence in a place where fear has not yet been introduced.

Sam lowered the bird gently back into the nest, slid back to the boat, and smiled.

“Now—ain’t that something,” he whispered.

“I don’t believe you did that.”

He laughed softly. “If the chicks had been around like in early spring, it mighta been harder. They get a bit edgy when the youngsters come. But they fine now.”

He was silent for a while, still touched by a place he knew so well. Then he added: “An’ you should see ’em fly. They go up soaring—up to two thousand feet and more…. Lord, they so beautiful.”

And, as if in agreement, five males blew their red balloons simultaneously while the females nodded their downy white heads.

We floated deeper and deeper into the mangroves and saw hundreds more frigate birds, all equally tame and unconcerned by our presence.

“Sam, this is a wonderful place.”

Sam smiled and nodded.

“Sam, I’m going to stay.”

“You goin’ to stay where?”

“Here. On the island. Maybe find a beach and just stay here awhile.”

He looked serious.

“There’s a place you can stay in Codrington. I can—”

“No. I just want a beach and a bit of shade. I’ve got enough food for a few days. And water. I’ve got water.”

He looked at me and grinned.

“We got a real live Mr. Robinson Crusoe here!”

“Yes—that’s it. A few days of Robinson Crusoe living. There aren’t many places left like this—especially in the Caribbean. I’d like to give it a try.”

He shook his head and chuckled. “You crazy.”

“Yes, I know.”

He thought for a while. “Listen—if you go on the east side over by the caves there’s a whole lot of beaches. No one goes there.”

“What about on this side?”

“Well—there’s a beach—a real long one—Seventeen Mile Beach, they call it—goes all the way down the other side of the lagoon. Pink sand, palm trees….”

“And no people?”

“Yeah—no people. No one. You got miles and miles of beach and no one. Couple of ponds with good water. Tha’s ’bout it.”

“Can you show me how to get there?”

He burst out laughing. “You jus’ like what they say about the Barbudans. People in Antigua think they crazy. Always doin’ things different. Don’t want development, don’t want tourists. Wan’ to just be left alone. They kept asking them British to let ’em go independent of Antigua. They still write to the queen asking! They wan’ to keep their land communal like it’s always been. They claim they got ‘rights’ since way back when they were slaves. They don’t want to be in the ‘Bird Cage’!”

“What Bird Cage?”

“Y’know—the Birds—Vere Bird, Lester Bird, Vere Bird, Jr.—all them Bird family that runs Antigua.”

I laughed. It was the first time I’d heard the expression, and from all I’d learned on “the big island” it seemed most appropriate.

“There’s this guy, Arthur Nibbs, young lawyer born on Barbuda. Chairman of the Barbuda Council. He really tells ’em: ‘Barbudans’ll do a mass suicide on the beaches if they don’t get independence from Antigua.’ He said that and most of ’em here, they agree with him. They just wan’ to be left alone. To be like they’ve always been. They like bein’ free—they like bein’ Robinson Crusoes!”