Lost Worlds (31 page)

Best of luck—mate. Wherever you are.

“Hey!” I shouted.

I had no choice. The whine, roar, and wind blast of the helicopter rotor blades made any kind of decorous conversation difficult. Something in my brain suggested I forget the formalities and cut, as they say, to the chase.

“Where’s the doors?” I shouted into the maelstrom.

Colin, the young, frisky-eyed pilot, turned, smiled, and mouthed a big Australian “Whaddayasay, mate?”

I bawled out the question again. Actually more of a screamed plea. He continued smiling. One of those cocky Crocodile Dundee “born in the bush and proud of it” kind of smiles.

“No doors, mate. Fasten the belt and stick your foot outside on the skid.”

I tried to smile back, but the grin got stuck in a grimace. No bloody doors? Foot outside on the skid? A seat belt that looked like an old piece of frayed rope? You’ve got to be joking. This is some kind of macho measuring test, right? Some weird form of outback initiation rite before I become a fully participating member of the beer ’n’ barbie club, a fair dinkum, roustabouting, good ole g’day-ing, good-on-yer-boyo-of-the-bush, ready to down his stubbies and steaks with the rest of the lads at the pub, admiring attractive “sheilas” and talking of nothing but cattle, cars, and carousing escapades.

Apparently not. This was no initiation.

“Hang on!”

Colin’s voice was lost in the screech of rotors and tornadoes of red dust that whirled around us as we lifted—no, that’s not the right word

—catapulted

ourselves into the air, at a force that placed my stomach somewhere between my feet, and my brain where my stomach once was.

And then the turn. No—wrong word again. More like a somersault as he banked the tiny doorless glass bubble and sent us, virtually at right angles to the ground, skimming over the scraggy tops of the eucalyptus trees, over the dry creek beds, over the spotty desert spinifex scrub and the thorn trees.

My leg (the one resting outside on the skid) turned to jelly as the wind roared past, trying to disengage my tenuous toehold on a hollow tube of metal less than an inch in diameter.

I’m going to fall…any second now, I’m going to fall right out of this damned thing. I saw a body tumbling…spinning rapidly earthward, leaving behind a frayed seat belt and a shiny spot on the skid where its foot had been, and a pilot smiling his outback grin and mouthing such traditional Aussie inanities as “She’ll be right, mate, she’ll be right.”

Ten minutes later I felt as if I’d been riding helicopters all my life. The fear was gone. Colin, who spent much of his time rounding up steers on Australia’s vast cattle stations, skimming the scrub tops, going

under

the lower branches of trees and missing desert boulders by heart-stopping inches (or so he told me), had given me a comprehensive display of his acrobatic skills. And I was still intact, leg on the skid, seat belt still miraculously fastened, and head and stomach comfortably back in their appropriate positions. I decided that a combination of fairground-thrill centrifugal forces and the benevolent watchfulness of higher powers had determined that I would live to fly another day. And so I relaxed and began to enjoy the experience and the scenery….

Once again I seem to be using the wrong words. “Scenery” hardly does justice to the Bungle Bungle—a unique, only recently discovered region of western Australia that contains some of the most remarkable and otherworldly rock formations on earth. We dallied awhile over the western flanks of this enormous twenty-by fifteen-mile red sandstone massif somewhere on the outer eastern edge of the Kimberley Ranges. I peered down into canyons, hundreds of feet deep, incised in the soft red rock. In some places they were a quarter of a mile wide, with palm trees and small spring-fed ponds reflecting the purpling evening sky. Elsewhere they were mere cracks, maybe a couple of yards across, that vanished into deep shadowy depths.

The top of the massif was basically a worn plateau, undulating in places, scoured and etched by the storms that scream across the barren plains of northwestern Australia. In crevasses and wind-carved bowls, a few hardy trees and bushes grew, their roots radiating like restless serpents seeking hidden pockets of moisture. Elsewhere was just more rock, rust-red sandstone, easing out in all directions before ending abruptly in enormous cliffs and crags, where birds circled on the updrafts and the summit dropped away suddenly to the dun-colored desert floor far below.

“Fantastic!” I shouted.

Colin turned and, giving me a “Y’aint seen nothing yet” smile, veered off abruptly to the eastern edges of the massif, where eroded formations, previously hidden, slowly emerged in the dusk light.

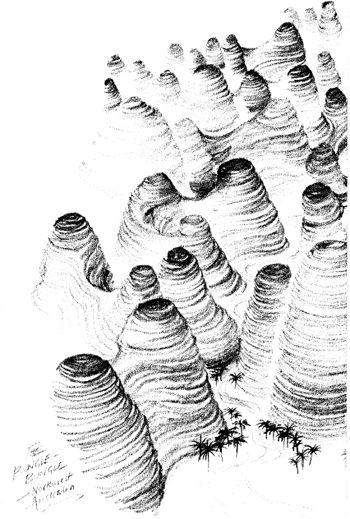

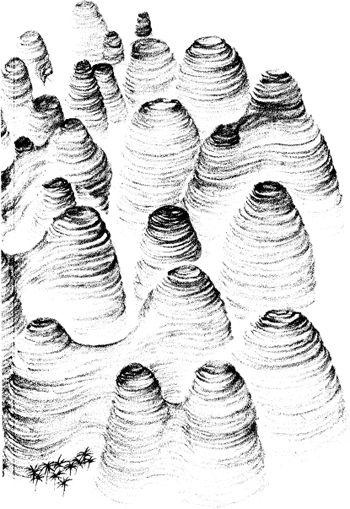

“They call ’em the Beehives,” he said nonchalantly as we hovered above a most amazing sight—hundreds upon hundreds of interlocking pinnacles, ridges, and domes, perfectly rounded and smoothed to beehive-shaped formations, rising from gently curling stream beds that gave a jigsaw-puzzle appearance to their intricate patterning. Each pinnacle was striated with evenly layered horizontal strata ranging in color from the lightest ocher to the darkest of bronzes and blood reds, as if some master artist had carefully painted every one with exacting precision over the long centuries of slow rounding down.

I’d never seen a sight like this before. I was entranced by the swirling complexity of the shapes and the unity and colors of the grouped forms. We floated over and between them like an eagle buoyed by thermals. I was no longer aware of Colin’s doubtlessly clever looping antics. The magic and mystery of this place, only officially “discovered” in 1983 and still not accurately mapped, enveloped me. I had come a long, long way to be here, and it was everything that the world wanderers’ grapevine had said it would be. A true lost world, offering its power and its beauty to only a fortunate few who had sought to learn its secrets.

The Bungle Bungle—or, to give it the correct Aboriginal name, Purnululu—has been known to only a handful of secretive outbackers since 1879. However, following Roger Garwood’s photographic assignment in 1981 for the Western Australian Department of Tourism to “find additional places of interest around the Kimberley region” and a special TV documentary on the area in 1983, the Bungle Bungle was acclaimed as “one of the most fascinating sights in the undiscovered northwest.”

This vast maze of multihued sandstone domes and incised canyons is indeed one of nature’s most spectacular masterpieces. Occupied on the fringes by the Purnululu Aborigines for over twenty thousand years, the region emerged initially over three hundred and fifty million years ago as the Kimberley Ranges to the west were eroded by streams that carried the sand and quartz sediment eastward into the vast Hardman Basin. What began as a huge depository plateau was gradually striated by sudden and torrential rains and streams that dissolved the binding quartz and quickly cut down through the soft sandstone. Had it not been for the coating action of quartz, iron ore grains, and lichen that created a protective “skin” over the soft sandstone, the region may already have been eroded down to an ignominious peneplain.

The vicious scouring action of sudden floods created canyons sometimes more than three hundred feet deep but in places less than four feet wide. Hundreds of rounded “beehive” pillars were left as the canyons on the southern and eastern extremities were broadened to form today’s fantasy-land jigsaw shapes, ribbed with bands of gray and iron-red strata.

Altogether one of the most unusual landscapes in the world.

My long Australian outback odyssey began in Sydney on a bright cool October day on the cusp of the Southern Hemisphere’s summer. I’d only paused for a brief stopover in the city to recover from the long—far too long—flight from Los Angeles. But when I took a cab into the city from the airport, I decided to stay awhile longer.

“Do y’wanna bit of a tour, mate? Won’t cost y’much.”

“Sure.”

It didn’t cost much and I was entranced.

A city magazine masthead boasts “Sydney—best address on earth,” and I quickly began to understand the immodest claim.

The 1778 birthplace of Australia is today a cutting-edge colossus of almost four million hurry-scurry inhabitants (more than a quarter of the entire population of the country!). From its gleaming downtown towers and booming waterfront extravaganzas, its endlessly varied ethnic restaurants, its iconoclastic wing-roofed opera house, and its burly landmark harbor bridge, to the delicate brick rowhouses (still with red tin roofs), huge swaths of gum-tree-shaded parks, and the erotic delights of King’s Cross, Sydney (known as “The Big Smoke”) booms and swings and shimmers and shows off its charms with all the wild exuberance of Tina Turner struttin’ her stuff at a bacchanalian birthday ball. Despite the decorous undertones of a city proud of its long history, its cultural institutions, its palatial waterside homes, and its intellectual underpinnings, the place is a frenetic flavor-of-the-month enclave. It has “party time!” plastered all over it and you can’t help but go with its vivacious flow, from brilliant golden dawns across the harbor to nighttime frolics at rock clubs and waterside pubs and along the funky surfside hub of Bondi Beach. Sydney is a place you don’t forget—a place that entices you to stay on, to live there awhile, in style, in its brilliant clean light, riding the roller coaster of the new Australia, with its nouveau riche hero-entrepreneurs (Kerry Packer, Alan Bond, et al.); its new melting pot ethnic ethos; its cultural renaissance sparked in good Aussie movies, the landscape paintings of Sidney Nolan, the novels of Patrick White, the poems of Ian Mudie, even the sexy sassiness of Olivia Newton-John—and its wholehearted celebration of leisure and blithe-life living.

I left tired, but reluctantly, after two days of nonstop gallivanting in this gregarious, full-of-gusto place. I wouldn’t be seeing cities for a while. Urbane urges would have to be sublimated and exchanged for the echoing drone of Aboriginal didgeridoos and the howl of wild dingo dogs and the “meat pie and g’day, mate” fellowship of bush bums in the great red outback that is most of the rest of Australia.

No worries, I told myself in the Strine dialect I was rapidly learning, she’ll be right.

And—all in all—(allowing for a couple of near-death experiences) she was.

So—off I soared out of Sydney on yet one more crystal-clean late spring morning, heading northwest via Alice Springs to the recent earthquake-decimated (now rebuilt) town of Darwin, way up on the tip of the northern territory.

The last leg of this long series of flights would bring me down to the town of Kununurra in western Australia, start of my desert odyssey to the Bungle Bungle and the “never-never” nothingness beyond.

Writers and artists—even composers—have often tried (usually unsuccessfully) to express the vast scale of this empty land—the endless, unpeopled redness, and the flat, worn-down, and oh-so-ancient remnants of ridges and ranges that are now mere stumps and eroded humps, hardly noticeable at all from thirty-five thousand feet against Australia’s hazy hugeness.

There was something frighteningly indifferent, inhuman, in the land below. Even the Sahara from above displays an ever-changing repertoire of textures and colors with occasional welcoming clusters of palms around scattered oases. But I saw few such subtleties here. It looked like a dead and utterly alien place. Like the surface of some lost red planet out in the eternal silence of the cosmos. I only hoped that on closer acquaintance, I might find more comforting signs of life and growth and the presence of people, most of whom now cling to their coastline cities and towns and leave the outback to the scattered swagmen and stock hands and the relentless scouring of a cruel and vicious climate.

I never discovered the reasons for all the delays at Darwin, although everyone seemed to accept them as a matter of course—a regular dues-paying ritual for those crazy enough to be flying so deep into the outback.

“Y’should’ve bin here last week, mate.” A big burly man in jeans and floppy sweat-stained leather hat spoke to me from a nearby seat in the terminal. “Talk about bloody chaos. Two flights canceled back to back. Storms more’n likely. You’re in the storm season now—the wet—so y’gotta expect anything. Four hundred stuck in this bloody terminal. Fans not working right, Coke machine empty. No food. No grog. Tell y’mate, place was like a bloody stockyard—full of stinkin’ mad bulls.”