Louis S. Warren (23 page)

Authors: Buffalo Bill's America: William Cody,the Wild West Show

Tags: #State & Local, #Buffalo Bill, #Entertainers, #West (AK; CA; CO; HI; ID; MT; NV; UT; WY), #Frontier and Pioneer Life - West (U.S.), #Biography, #Adventurers & Explorers, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #Fiction, #United States, #General, #Pioneers - West (U.S.), #Historical, #Frontier and Pioneer Life, #Biography & Autobiography, #Pioneers, #West (U.S.), #Civil War Period (1850-1877), #Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show, #Entertainers - United States, #History

THE VIGOROUS COMPETITION between Cody and Custer suggests how much buffalo hunting was a realm of commerce and theater, in which the best guides packaged a whole range of signal “frontier experiences” for their clients. The most popular guides provided keys not only to game but to the mystique of wilderness, which they embodied. Of course, where Cody's reputation as a white Indian who was certifiably

white

facilitated his appeal as an army scout, it complemented his career as a hunting guide. White men who were sports, after all, wanted to believe not only that Buffalo Bill was the greatest guide and hunter of all time, but that he represented their own potential for hunting prowess and frontier mastery.

In the 1860s, many sportsmen utilized army connections so they could ride with the U.S. Cavalry, whose commanders were eagerâwithin limitsâ to cultivate good relations with influential voters and financiers, and who often saw killing buffalo as an indirect way of fighting Indians. Many sport hunters turned to Phil Sheridan, who commanded all the forts west of the Missouri River, for advice about where to hunt and which guide to hire. In turn, he frequently referred them to Cody. The confluence of wealthy hunters, army officers, and frontier scouts gave Cody some of his first press among a social elite he came to admire and which he sought to join. Indeed, Cody's reputation as a hunter and guide grew in concert with his reputation as an Indian fighter, partly because of reports that began to filter through army hunting circles about his skills and his helpful demeanor.

Thus, one year after the Summit Spring fight, in the summer of 1870, General Carr hosted a half-dozen tourist hunters from England and Syracuse, New York, on a buffalo hunting trip into the Republican River country. Along with a trooper escort went scouts William Cody and Luther North. Later, in December, Cody, Luther North, and Frank North guided for a combined army-civilian hunting party which included James W. Wadsworth, a New York congressman, a number of railroad dignitaries, and several officers from Fort McPherson.

64

A steady stream of sport hunters kept officers and guides busy, at Fort McPherson and elsewhere, for much of the 1870s. There were sport hunters from nearby Omaha in September 1872. Later, Sheridan himself invited the Earl of Dunraven to hunt buffalo, guided by Cody and Texas Jack Omohundro. George Bird Grinnell went hunting with Omohundro and the North brothers in the summer of 1872.

65

Such outings became so common, and constituted such a drag on thinly stretched military resources, that they emerged as a subject of complaint among post commanders, particularly those in better hunting grounds. Modern readers might assume that army families most dreaded news of Indian hostility. But in 1870, wrote Libbie Custer, she and her husband, George, would “tremble at every dispatch for fear it announces buffalo hunters.”

66

Requests for guides and protection were hard for officers to refuse. Many of the businessmen who wanted them were Union army veterans, with personal connections to powerful generals and politicians. Supporting their recreation was a way of earning their support for better army funding in the continuing wrangle between the War Department and other branches of the federal government.

67

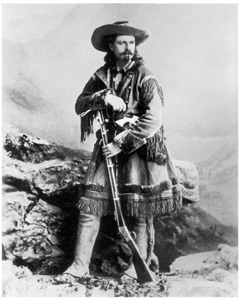

Cody in

1873â74,

as he dressed for scouting missions and

guided hunts. Courtesy Buffalo Bill Historical Center.

Apparently, Cody saw guiding as a two-pronged business. On the one hand, a guide had to lead his clients to game. He did everything he could to see they bagged their fill of Plains buffalo, antelope, elk, and deer.

68

But on the other hand, the guide had to be able to bundle a host of other experiences and deliver them in a particular manner. The ideal buffalo hunting guide was an expert not just in finding buffalo but in killing themâin the prescribed manner, of course. Whether he was fashioning his image to the needs of his audience, or indulging cultural longings he shared with other middle-class men of his era, or both, Cody achieved prowess as a mounted hunter that was astonishing, even to the most skilled Plains hunters. In 1870 Luther North, a scout whose resentment of Cody's fame verged on open hostility, watched him kill sixteen buffalo with sixteen shots from the back of a skittish horse, awing an audience of sports. The episode may have been the source for Cody's story of killing thirty-six buffalo (and, later, forty-eight) in one run. According to North, Cody was never known for being a pistol shot, and his marksmanship on foot was only good. But “on horseback he was in a class by himself,” his “exhibition” of buffalo killing “the most remarkable I ever saw.”

69

North had many friends among the Pawnees, whose language he spoke fluently. According to him, Pawnee hunters, who killed buffalo all their lives and who knew a great hunter when they saw one, also witnessed Cody's string of sixteen kills. To them, wrote North, “his buffalo killing was miraculous.”

70

In addition to providing the spectacle and experience of the mounted hunt, the ideal Plains hunt included at least some manifestation, or sign, of Indians. For many, buffalo hunting was a kind of stand-in for Indian killing. Tourists spoke of buffalo “tribes” and took “scalps” from their hides, and as they embarked on hunting expeditions, they sometimes hoped aloud for a chance to fight Indians, or at least to see them, so they could tell the story on their return.

71

Such longings were expressions of a common, complex American desire. The proximity of Indians was potentially dangerous, but paradoxically, even as the war on the Plains unfolded, tourists were entranced by them. Over most of the United States, the experience of meeting Indians had retreated from daily life into the dim mists of history. As it did so, Americans became even more drawn to encounters with Indians, who come to stand for something more than just other people. By the early part of the nineteenth century, they were markers of American identity. For the broad middle class, by the 1860s, Indians already embodied the presence of history and authentic nature; they signified freedom from the artifice of modern industrialism, the market, and the city.

Few tourists ever fought Indians, and judging by their actions, they did not need a skirmish to authenticate their frontier experience. General Carr often requested the services of the Pawnee scouts on hunting expeditions to provide both protection from the enemy and the companionship of authentic Indians. But he was not the first to exploit their performance capabilities. In 1866, the Union Pacific railroad hired the first battalion of Pawnee auxiliaries, under the command of white frontiersman Frank North, to defend railroad workers from Sioux and Cheyenne raiding parties. The proximity of the Pawnees to the railroad soon brought them into the tourist business. That year, a party of eminent politicians, journalists, and financiers journeyed to the hundredth meridian, courtesy of the Union Pacific's directors, in celebration of the company's successes. This carefully arranged tour included not only a real, miles-long prairie fire set by excursion managers, but displays of Pawnee war dances, a mock fight between Indians (with some of the Pawnee dressed as Sioux), and a mock Indian attack (again by the Pawnees) on the excursion party itself as they camped outside of Colville, Nebraska.

72

It is hardly surprising that with experience like this to their credit, many Pawnees would join the Wild West show less than two decades later.

73

For the hundredth meridian excursion was, of course, a show, stage-managed to connect the powerful audience with a sequence of attractions: Indian war dances, battles, an Indian attack, and a prairie fire, all as a kind of primitive counterpoint to the railroad itself, the paragon of technological mastery and the advancement of civilization. Set against the railroad, the attractions suggested a story about the progress of civilization from ancient savagery in the wilderness to modern machines and manufactured comfort. Silas Seymour, who organized the tour, was not by profession a showman. He was an engineer. But cultural longings for prairie fires and Indians as savage signifiers were so pervasive that he had no trouble imagining that his party would enjoy them.

William Cody was nowhere near the Union Pacific line in 1866. He probably did not know about Seymour's show. But he did know about the desires and longings of American tourists on the frontier, for guides and hosts played to them across Kansas and Nebraska. Perhaps he heard about another hunting expedition by some Union Pacific executives in 1867, during which Traveling Bear, a Pawnee scout who accompanied the party, impressed the crowd by shooting an arrow right through a buffalo.

74

Riding with the North brothers and the Pawnees in the late 1860s and the 1870s, Cody had many opportunities to absorb the importance of Indians to sport hunters.

But Indians were not always available or willing to accompany sports, and when they were, guides who hired them had to share the compensation. Also, although proximity to Indians potentially accorded “white Indianness” to guides, recruiting them required more expertise than Cody actually hadâthus, Carr's hunt in 1870 depended on the assistance of the Norths. Guides, in other words, were entertainers who delivered the trappings, or aura, of Indianness for their clients. Cody learned, as had other guides, to provide a “safer,” cheaper Indian context through his own ostensible expertise in what today we would call Indian culture, a knowledge he conveyed in camp stories.

The few fragments we have of Cody's oral performances suggest that in circles of light around Plains campfires, with audiences of city dudes, he began crafting tales which later appeared in his autobiography and in his lifelong performance of Buffalo Bill's Indian adventures in the press and in the arena. The campfire light focused attention on him as a narrator, creating a kind of open-air auditorium for tall tales, in the performance of which lay seeds of his entire career. Where Hickok's tales urged audiences to debate how much he could be believed, Cody's method was more subtle. His mingling of truth and fiction was so artful that his stories were less obviously fictional than Hickok's. He followed accounts of Indian ambushes with advice about how to avoid Indian attack. “When you are alone, and a party of Indians are discovered, never let them approach you. If in the saddle, and escape or concealment is impossible, dismount, and motion them back with your gun.” Such adviceârunning or hiding is preferable to fightingâwas sensible, and seemingly down-to-earth. But at the same time, he exploited his fund of Plains lore by recounting battles fought by other people as well as himself, making himself the hero of more fights than he had seen. “Bill was the hero of many Indian battles,” wrote one excursionist Cody guided in the late 1860s. He “had fought savages in all ways and at all hours, on horseback and on foot, at night and in daytime alike.”

75

Just as important as the content of his stories was his artful self-presentation, his attention to props and setting, which was unsurpassed. As one hunter wrote, “Bill was dressed in a buckskin suit, trimmed with fur, and wore a black slouch hat, his long hair hanging in ringlets down his shoulders.” His stories of “hunting experiences since he was old enough to ride a horseâfor Bill was born and brought up on the Plainsâare truly wonderful to hear related, as they are, around our blazing camp fires, and in the presence of all the paraphernalia of frontier life upon the Plains.”

76

Between the sun-splashed grassland, across which he chased and shot buffalo looking for all the world like the fantasy hunter out of a painting or a novel, and the flickering circles of campfire light where his audience sat spellbound by his stories, Cody found a stage for an ongoing performance. Here he invented the character of Buffalo Bill, and much of his heroic life story. His open-air show invited clients to project their fantasies onto him, to partake of frontier nature through him, to revel in the inevitable progress he and they together represented: sports and guide united, clearers of the land, savoring the fast-retreating wilderness, rooting themselves in it, even as they swept it away.

77

THE SOCIAL CHALLENGES of guiding sharpened Cody's development of the hunt spectacle. Guided hunts were exercises in manly bonding, and when they carried off their performance, guides' mystique conveyed a kind of natural aristocracy, a fraternity of hunters, beyond class boundaries. Ideally, the artificial ranks and false privileges of urban life melted away in the wilderness.

But guides walked a fine line between courteous assistance and fawning subservience. They were, after all, hired hands, employees of their clients, who could be condescending and snide. To humiliate a guide was to challenge or discount his wilderness expertise. As such, it was a threat to the entire experience of the hunt. With the hardships of all-day rides and the frustrations of buffalo hunting so common among novices, short tempers abounded. One rude client in a party could undermine the theater of the guided hunt.