Louis S. Warren (54 page)

Authors: Buffalo Bill's America: William Cody,the Wild West Show

Tags: #State & Local, #Buffalo Bill, #Entertainers, #West (AK; CA; CO; HI; ID; MT; NV; UT; WY), #Frontier and Pioneer Life - West (U.S.), #Biography, #Adventurers & Explorers, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #Fiction, #United States, #General, #Pioneers - West (U.S.), #Historical, #Frontier and Pioneer Life, #Biography & Autobiography, #Pioneers, #West (U.S.), #Civil War Period (1850-1877), #Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show, #Entertainers - United States, #History

On the other hand, such musings often called into question the racial viability of the English. Race, in the nineteenth century, was thought to be inherited through blood, but also subject to change by new environments.

108

“Of one stock” they may once have been, but were the two nations yet of the same race? Or had the frontier experience so altered the Americans that they had become something different? To see cowboys like Buck Taylor and Dick Johnson “amongst a group of self-complacent little City clerks it might be imagined that the individuals belonged to separate species.”

109

In 1888, the Metropolitan Police began their search for suspects in the Jack the Ripper murders by interrogating political radicals and racial minorities whose barbarous instincts might have incited the crimes. The Wild West company sailed for New York from Hull on May 11, 1888, inadvertently leaving behind at least four Lakota men who were lost in the city.

110

In their search for a way home, they went to London, where they were quickly picked up by the police. “The police questioned us and let us go,” Nick Black Elk recalled many years later. “They had probably blamed us with something that had happened.”

111

In addition to American Indians, police in pursuit of the Ripper interrogated socialists, “Asiatics,” and Greek Gypsies, before moving on to three more of Cody's own, “persons calling themselves Cowboys who belonged to the American Exhibition,” who had stayed behind in London, and whose racial identity was questionable enough to earn them a place on this list of potential savages.

112

After somebody claiming to be the murderer used what might have been American slang in several letters sent to the police and the press, some speculated that the butcher of Whitechapel might be a “Texas rough.” Such images of rough-hewn western violence, of course, resonated to some degree with the recently departed Wild West show and the many references to Texas that it called to mind. Although Cody attempted to fashion an image of his cowboys as “real” frontiersmen and safe, respectable entertainers, the facade was hard to maintain. Cowboys in the camp were on display for hours at a time, and they were often taunted or treated as museum exhibits. Indians and other performers suffered just as much, but white cowboys appear to have been less patient with objectification by fans. Late in 1887, Dick Johnson, the “giant cowboy,” got into a fistfight with another patron at a London pub. When the police arrived, Johnson tried to flee before engaging two constables in a bruising brawl. Although Cody and the Prince of Wales intervened in an attempt to lessen his punishment, Johnson did six months' hard labor at Pentonville Prison before rejoining the show in Manchester. The event was widely covered, in both the regular and the comic press, as if it confirmed the burgeoning savagery of American white men.

113

The conspicuous growth of American cultural and economic power conjured notions of British decline which only enhanced such anxieties about the ascendant “American race.” Even before Buffalo Bill's Wild West announced it was coming to London, such a flood of American investors, tourists, and entertainers had inundated Britain that critics began to fulminate about the “American Invasion.” Cody's popularity brought such concerns to a head. In the show business world, theater owners and managers, among them Bram Stoker, read commentary about the threat of competition from American shows.

114

Beyond entertainments and popular amusements, the proliferation of Cody's image and the symbols of his show announced the penetration of British industry and consumer markets by American capital, goods, and advertising. As one newspaper wit described it,

I may walk it, or 'bus it, or hansom it: still

I am faced by the features of Buffalo Bill.

Every hoarding is plastered, from East-end to West,

With his hat, coat, and countenance, lovelocks and vest.

115

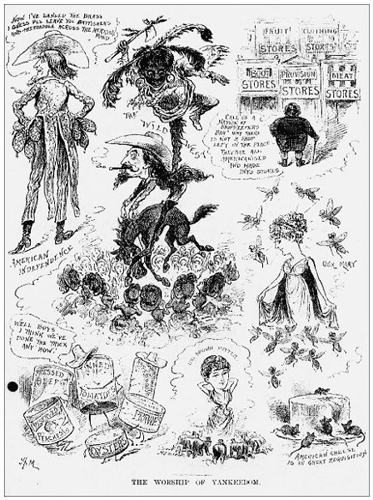

One cartoonist drew a montage of cartoons over the caption “The Worship of Yankeedom.” At the top left was Cody, portrayed as a sharp Yankee-gone-West, a spindle-shanked New Englander in a swallowtail coat and cowboy hat, his pockets bulging with coin. “Now I've landed the brass I guess I'll leave you Britishers and skeedaddle across the Herring Pond,” he announces.

Others images evoked the American commercial challenge even more directly. One portrayed a bowler-hatted Londoner confronting a whole series of buildings labeled “stores” and complaining, “Call us a nation of shopkeepers Bah! Why there is not a shop left in the placeâthey are all Americanised and made into stores.” Another showed a collection of canned goods whose labels identified them as “Preserved Peaches,” “Oysters,” “Prawns,” “Asparagus,” and “Tinned Tomatoes,” with this last can wearing a cowboy hat and announcing to the others, “Well Boys, I think we've done the trick anyhow!”

116

Such images were adaptations of an older European critique of America's hard-driving commercialism, a Yankee characteristic which alienated Old World cultural commentators for decades. Charles Dickens had announced years before that Americans were crass, finagling operators and cultural tyrants, and many other Europeans criticized Americans' relentless pursuit of manufacturing and the dollar to the exclusion of art, poetry, and humanity. America represented a gigantic paradox. Many continued to think of her as a primeval wilderness, where there was no culture, where Indians roamed a vast hinterland and Yankee settlers scrabbled in the forests. At the same time, her manufacturing, fierce market expansion, and corporate capitalism made the United States a metaphor for modernity.

117

The American Exhibition of 1887 captured both these facets, with an exhibit of American products joined by a bridge to the Wild West camp. But Cody's giant commercial success in London, the ubiquity of his advertising and the crowds of paying customers, in a sense made the manufactured exhibits redundant. Buffalo Bill's commercialism embodied the paradox of America, and captured every single anxiety about a foreign power that seemed both wilderness and commodity, culturally impoverished and perpetually for sale.

Cody's sexual appeal made the leap from these economic and cultural concerns to issues of biology, or race, that much easier, for the spectacle of an “invader” who was irresistible to English womanhood easily reinforced fears of English racial decline. At least one columnist compared him to Jung Bahadur, a Nepalese warrior prince whose visit to London in the 1850s included an affair with an Englishwoman, a scandalous event long remem bered in bawdy songs at late-night supper clubs.

118

Although journalists fixated on Cody's tent in the show camp, he spent most evenings in a rented London apartment, where another journalist recalled that he was “embarrassed by an overwhelming mass of flowers which come hourly from hosts of female admirers.”

119

Cody, as we shall see, enjoyed the company of women in London. When Bram Stoker received a note from Cody via a young woman, written on the American's calling card, requesting two seats at the Lyceum for one “lovely little actress,” the manager did not have to wonder who would be sitting in the second seat.

120

“The Worship of Yankeedom” criticizes American commercialism.

Note the parody of Cody, top left, in which the frontiersman is a

money-grubbing Yankee in disguise.

Moonshine,

October

22, 1887.

Cody's performance for Queen Victoria was charged with many different layers of irony and tension. Not the least of them centered on his appeal as a manly foreigner amusing the British monarch. His “conquest” of the notoriously reclusive queen sat uneasily with her public, and her patronage of the Paris Hippodrome and the American Wild West embittered British performers who waited in vain for her command. Vesta Tilley, a popular music hall singer, roused her audiences with comical but pointed verse:

She's seen the Yankee Buffaloes,

The circus, too, from France,

And may she reign until she gives

The English show a chance.

The queen's long absence from London's greatest cultural attraction, its theaters, particularly chagrined Londoners. “Her Majesty has honoured the French circus at Olympia and the American boom at the Buffalo Billeries with her presence, but never since the death of her beloved consort has she set foot, even as an august audience of one, in an English show place.”

121

Even performers in working-class music halls, like Vesta Tilley, took this as a slap.

May Queen Victoria Reign

May she with us long remain,

'Til Irving takes rank

With a war-painted Yank,

May good Queen Victoria Reign.

122

There was something more than envy in these demonstrations. Unrest in the London theatrical world echoed a wider public dissatisfaction with the queen's continuing insistence on private showings of the few entertainments she did attend, and exclusive, private viewings of public exhibits, including the American Exhibition, which was closed to the public during her visit. “It would not have done any harm had her Majesty, just for once, tolerated the presence of her subjects in the same public building as herself” when she attended the American Exhibition, wrote one columnist.

123

Wrote another, “It is evident by her recent actions that her Majesty is not altogether disinclined to be amused, provided, of course, that her subjects do not witness her enjoyment.”

124

The queen's unwillingness to be seen was a constant theme among penny papers and highbrow society journals because it was no trivial matter. Like the inhabitants of many nations, Britons were riven by distinct regional identities, class tensions, and fierce party differences, all of which were apparent in 1887 as they rarely had been before. Against the surge of Irish nationalism, workingmen's strife, and other disputes that tore at the fabric of the United Kingdom, “the Queen is the symbol of the unity of the nation; she represents the integrity of the Empire,” wrote the editor of

The World.

It was, after all, to see the queen that “her children, from every quarter of the world, flock to this island, recognising in it . . . their real home and Mother Country.”

125

With a monarchy that was long on tradition and short on ceremony, the foremost ritual of the British nation was the viewing of the queen.

126

She was the head both of the church and of the state. Royal representatives, symbols, and images of Queen Victoria were legion, but only the presence of this most hereditary monarch could provide her disparate peoples an authentic bond with the nation and its storied history. Only the proximity of her person allowed the ritual of nationhood to commence. For the great pageant that was the Jubilee, the celebration at a half-century's reign, to function as it should, for the nation to be united, the queen had to make an appearance, or, rather, many appearances. Her passage through a street or a hall allowed bystanders to unite in adoration, whether that meant cheering her coach or simply gathering to watch respectfully while she performed official duties. No other institution provided the cohesive power of the British monarchyâbut that power could only be exercised if she made herself visible to her subjects.

And this was the essence of her failing in 1887, a reclusiveness so complete that it bordered on a crisis of state. Controversy swirled around her unwillingness to be seen on the way to the Jubilee service at Westminster Abbey, with editorialists lamenting that “the reasonable wishes of hundreds of thousands of people to see the Queen on her way to the Abbey, and to witness some kind of State, have been yielded to with extreme reluctance.”

127

Observed another, “The Monarchy is in part a pageant and a symbol, and a pageant which is not displayed, a symbol which is not shown, cease to be a pageant and a symbol.”

128

At a moment when socialists advanced the cause of abolishing the monarchy, these critics implicitly made the point that Victoria's ongoing seclusion was doing the job for them. Describing her tour of the working-class districts of the East End, one journalist was troubled by the pointed reproofs to the crown in the banners draped across the street: “God bless our Queen. May she come more frequently to the East End” and “We love our Queen, but we don't often see her.” Such informal, and reproachful, messages gave the impression that “long disuse and hard times have both helped to make street adornment a lost art in London.”

129

If only Victoria would be seen more often, “street adornment” and its corollary, class deference, could perhaps be reestablished.

This was the political context of the Wild West show's audience with Queen Victoria. In a limited sense, Cody's attraction was analogous to the queen's. The “representative man” of the American frontier was a living bond between spectators and the frontier history of Britain's former colonies, just as the queen connected her audience to mythic national unity. But where Cody's show was an amusement that allowed spectators to decide what was real man and what was representation, where authentic frontier stopped and fake began, Victoria's authentic presence among her subjects was the central pillar of the British state. Commentators insisted on it because, for all the superficial similarities between royal appearances and show business, the queen's progress was not just another “show.” In this sense, Codyâshowman, businessman, and Americanâwas an unsuitable attraction to place before her hallowed British self. For many Britons, her eagerness to be seen by his large assemblage of primitives, but not by her own subjects, was insulting and worrisome.