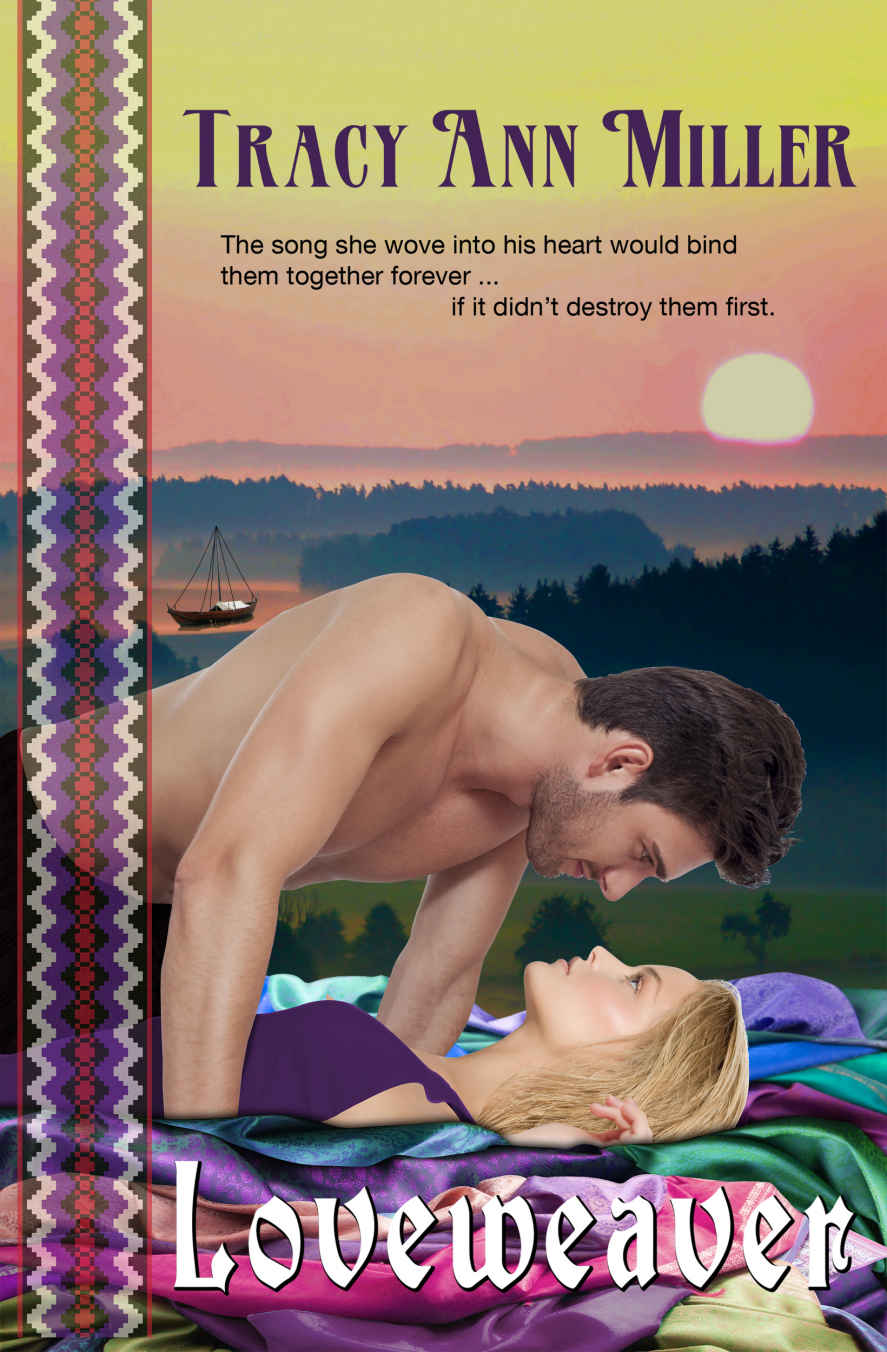

Loveweaver

Authors: Tracy Ann Miller

Loveweaver

Tracy Ann Miller

Copyright 2016

Tracy Ann Miller

Cover Art by Tracy Ann Miller

Photography Credits to:

Photographerlondon

Serrnovik

Iconogenic

and

Tt

Fear naught, far traveler, crossing mountain and sea.

Blind faith and luck also journey with thee.

Hedeby, Denmark. Summer 895

Llyrica wondered what price she would pay this time, to save her brother’s neck.

“I will take the entire purse, Solvieg.” Llyrica covered her face with the gray veil, opaque with two tiny holes for her eyes. “Since we have no notion of Broder’s folly, I had best be prepared.” The ratty cloak she swung around her shoulders would disguise her slim body, and she pulled the hood low to hide every strand of her white gold hair. The garments would soon heat Llyrica to a broil on this summer day, but were necessary to assure her anonymity.

Aunt Solvieg, her deformed face tight-lipped and full of doubt, gripped the moneybag. It contained their life savings: coins, rings, beads and bits of gold and silver. Much of it was a newly received payment for two barrels of quality cloth and exquisite braids now sitting in the harbor, aboard a merchant ship. The two women’s wovengoods, scented with dried gingerroot, would find their way first to Jutland, and then to ports all over world.

“I still say let me go in your stead!” Solvieg protested. “I have more practice getting him out of trouble. Years of practice.” Her effort to rise from the stool proved too much. The keys, rings and knife hanging from the chains of her shoulder brooch jangled as she fell back.

Llyrica leaned in to kiss her wild-haired aunt, took the drawstring purse, then started for the door. “Soso, you scarcely made the trip to market and back yesterday. Now your hip and leg are swelled again. Be still! I must hurry to avoid further tragedy!” Her hand lay on the latch. “I will run, wearing this costume of yours, hobbling as you would, stooped like the crone they all think you are, and none will know I am not the hideous woman of the loom! I have done it before with success and will do it now.”

Solvieg shook her head. “We have both watched our profits,

your future

, once more poured out to settle your brother’s trouble!”

At the mention of Llyrica’s future, she and Solvieg exchanged glances of understanding. Mother’s last words to her eight-year-old daughter had never faded. But long years of hiding in fear had prevented Llyrica from pursuing the deathbed promise. She almost welcomed these antics of Broder’s. They kept her too occupied to plan a journey of revenge.

“What has he done this time?” Soso asked. “Set fire to a haystack? Committed petty theft? Let someone’s hogs loose? Run through the village with those ruffian friends of his, disturbing the ...”

“We will talk of it later! I must away!” Llyrica called over her shoulder as she rushed through the door, hearing it bang shut behind her.

“Make things right, but give away only what you must!” Solvieg shouted from within. But Llyrica already hurried along the peat path toward Hedeby’s rear gate, assuming the bent back and limp of gimpy old woman.

She glimpsed back briefly at the sod hut, build halfway into the side of a hill, with smoke trailing in a thin stream from a grass roof. The Crone’s Cave, so called by the townspeople, sat tucked almost hidden in copse of spindly evergreen. Beyond it, the heath spread out as her playground, known to her only at night, under the cover of darkness.

Folks knew that an old weaver of great skill lived in the cave, traded at market once a moon, and paid a fee to the jarl in exchange she be left alone. The town remained unaware that any other than one hideous woman and one troublesome man-child lived there. Solvieg played her part and Broder ran wild.

But Llyrica had made sure that she remained an undiscovered secret for twelve years. Mother’s words seemed never far.

Promise me, Llyrica! That your father never find you!

The guard at the gatetower waved her through the pass in the earthwork wall, which ran the perimeter of Hedeby, then pointed. “It happened at the docks!” he shouted down.

Nodding, she clutched the money purse beneath the cloak. Hunched in her guise of old loomstress, she continued her sideways gait along the wooden quay between rows of wattle and daub houses. She won looks of fearful respect from women in their vegetable gardens or yards where they hung laundry, babes on their hips, toddlers at their feet. Men frowned at her shrouded figure from huts of trade and pens of steamy livestock.

Hiding her identity behind a veil allowed Llyrica to see the world and judge her subtle influence upon it. Villagers adorned their garments with the braid of her tablet loom, giving credit for its beauty to a reclusive crone. Little would they guess of her weaving songs - spells woven into the design to ease the wearer’s life. Her lyrics of good health might strengthen a child or ailing elder. A melody of fortune might ensure a prosperous negotiation. Lovers would kiss, bound by a lovespell. A warrior might vanquish his foe by benefit of Llyrica’s victory song.

This was her life as a woman unseen, weaving gifts to the world as her mother and grandmother had done.

One day I, too, will be known as the Songweaver.

But at times such as these, Llyrica observed life through a mask, while her brother mixed in the thick of it.

“He is in for it this time!” The ironsmith shouted as she limped past. “It will cost you greatly!” His two thralls echoed his opinion, joined him in a hearty laugh.

Llyrica did not reply as she turned a corner toward the dockyard. She could not count the occasions that she and Solvieg had heard such statements and found them to be true. Llyrica had been too soft on Broder, her undisciplined brother of sixteen winters. She loved him too much, forgave him too often. Bailed him out too many times.

The quay ended as the stream widened, opening unto Hedeby’s harbor, its fame as a major trading port made apparent by the crush of Viking knorrs, fishing boats, and merchant ships moored and anchored in the bay. Wooden stalls were already vacant for the day. Furs, iron works, pottery and glassware had been packed up, livestock led away and the vendors off for home. Some, according to Broder’s tales, headed straight for the ale lodge for carousing. He had been there himself, he said, and described the place as thick with sour smoke, sweaty males, lewd sagas and debauched women. Perhaps one day, from within Solvieg’s disguise, Llyrica would get a glimpse inside and satisfy another of her many curiosities.

Gulls reeled and circled overhead, brought to Llyrica’s attention a circle of angry men and the noisy crowd gathered around them. Now she saw where the vendors had gone, and it looked as though much of the village had also left in the midst of its late day routine. Men still had axes, hammers and rakes in their hands, while women held babies, baskets of clothes, brooms, buckets and spindles.

Llyrica’s stomach jumped as she imagined her brother the subject of the debate. She took a deep breath, prepared to enter the hub and pluck him out.

In nobleman’s garments, a man emerged from a huddle and stalked toward her. He was the jarl’s reeve, Haldor, by Solvieg’s description. His frustration over Broder’s antics had often been appeased by Soso’s bribes.

“I doubt you will buy his way out this time, old woman,” the gray-bearded thegn said. “With me

or

with them!” He jerked his head in the direction of the crowd. “I wash my hands of it! You and the injured party will settle it among yourselves!” With a fling of his cloak and a spin on his heel, he brushed past her.

“The hag has come!” Someone shouted as Llyrica drew nearer, dragging one foot through the sand. Heads turned toward her as the villagers spread open. A group of men was revealed, the core of the grievance. The clamor quieted at her approach, her proximity now close enough for her to analyze, through her veil, the aftermath of a bloody deed. Llyrica sucked a breath.

A body lay dead at Broder’s feet.

With his step forward, a large man with sloping shoulders and round middle, seemed to declare himself the captain of a sweat-drenched, motley dozen. They were as varied in their exotic garbs as they were of ethnic origins, skin colors and hair modes. Llyrica spotted two Dane’s among them, but otherwise, they must be a collection of men from across foreign lands. Traders, certainly, but not ordinary. Dear Lord, they bore the mark which boasted of their profession as flesh peddlers, an x described by Solvieg, scarred onto the backs of their hands.

Broder, pray you have not picked a fight with slavers!

A drunken lot, to boot, by the smell of them, the sway of their stances and the beakers yet tipped up to thirsty mouths. Including the captain’s. Broder looked to have dipped his horn in a cask of ale, as well, if his glazed expression gave testimony.

Though the captain’s red face did not incite repulsion, its flabbiness and uncombed beard detracted from any positive features it might possess. His eyes appeared watery as if from crying.

“So you are his keeper, old woman?” He slurred his words in an unfamiliar accent. “Your local magistrate said you would come and we are to settle with you. Whatever you have brought, it is not enough to pay for the death of my crewman. I demand a life in exchange for one I regarded with affection!” His belch erupted, punctuating his exclamation.

The man drew sympathy from Llyrica, but she clung to her wits, pitied her brother for his wide-eyed panic. She feared the meaning of Broder’s blood-soaked tunica and hands. His large muscled frame bowed in guilt, and his hair, a light gold like hers, stuck to his head and neck with sweat. This would not be so easy to settle as an overturned vegetable cart. Neither could she console her brother in the present circumstances, though she longed to.

“Broder is no murderer,” she rasped in an old, scaly voice. “Who are you, and can you tell me what has transpired?”

“I am Xanthus, merely come to Hedeby with my crew to stop and trade. This boy of yours ran with his fellow rabble, now scurried off, and provoked Gerlach here into a wrestling match.” Xanthus nudged the dead body with the toe of his green leather boot. “Pulled a knife out of nowhere and gutted him.” He swigged from his beaker, wiped his mouth with the back of his hand and looked ready to burst into tears.

Xanthus’ twelve yelled their agreement in unison, and with intoxicated grins and clenched fists, exhibited their desire to see retribution. Llyrica eyed Broder as the furor rose up, received her brother’s denial, a subtle shake of his head. The gathered villagers, used to serving as witnesses to disputes, though seldom to charges of murder, shifted uncomfortably on their feet. Llyrica let the noise die down before she responded, and prayed she would not sound shaken.

Please, Broder. Remember as always not to reveal my true identity.

“And what is Broder’s side of the tale?” She turned to address her brother. “Did you challenge Gerlach, then kill him unawares?”

Broder swallowed hard, an audible sound. “Xanthus and his men came upon my comrades and me, there in Dyre’s ale lodge.” He pointed to the run-down longhouse. “Aye, friendly talk soon came up that Gerlach and I could wrestle for a wager among us all. So we agreed, then came here to the yard and began. It was a fair match, evenly made in our skills and size. But Gerlach forced me into a hold upon the sand, with a death grip around my throat.” Broder peeled back his plastered hair to reveal bruises in blue splotches on his throat. Displayed there, too, was the braid that Llyrica had woven for him as a child. Faded with age, it trimmed the neck of his tunica. Later, Llyrica would take time to wonder if it had saved his life.

Broder continued. “I conceded to defeat, but when he did not relent, but instead continued to choke me as his cohorts jeered and my comrades could not pry him from me ... I feared for my life ... and I pulled my dagger ... and aye ... I gutted him.” Llyrica’s eye fell to the knife, resheathed at his belt.

Half of Xanthus’ twelve protested Broder’s version of events, while the remaining exploded into drunken laughter. After draining the ale from his beaker, the captain tossed it aside, then crossed his arms over his chest. He staggered a step closer to Llyrica.

“Your boy was in no danger! If he had waited but another moment, he and Gerlach would be inside the lodge now, drinking their weight in ale, then have a pissing contest as new companions. As it is, I have lost a man who will be greatly missed. I need repayment!” Xanthus blustered. “His life for Gerlach’s would even the score! And relieve my grief!”

“Did anyone impartial witness this event?” She addressed the crowd with a crackling hiss. “Can anyone attest to the fact that Broder acted in self-defense? And even if he did not, accidents occur when men fight. The price should not be his life!”

Askew glances and ambiguous murmurs came from the standers-by, who chose not to invoke the wrath of the Xanthus and his motley dozen. It vexed Llyrica that Broder had chosen the opposite.

Xanthus must have taken the crowd’s reticence as a vote for his defense. He motioned for two of his largest men, one with a twisted red beard and the other with a stringy black, to take hold of Broder.

Llyrica determined Xanthus’ drunken grief and his notion of justice rendered him impervious to rational thinking. She feared he would now command a third man to step out from the twelve and plunge a blade of reparation into her brother. These thoughts impelled her to leap toward Broder and back against him as a kind of shield. Her small form though, would provide little protection against a dagger. She thrust forth the money purse out from under the folds of her cloak.