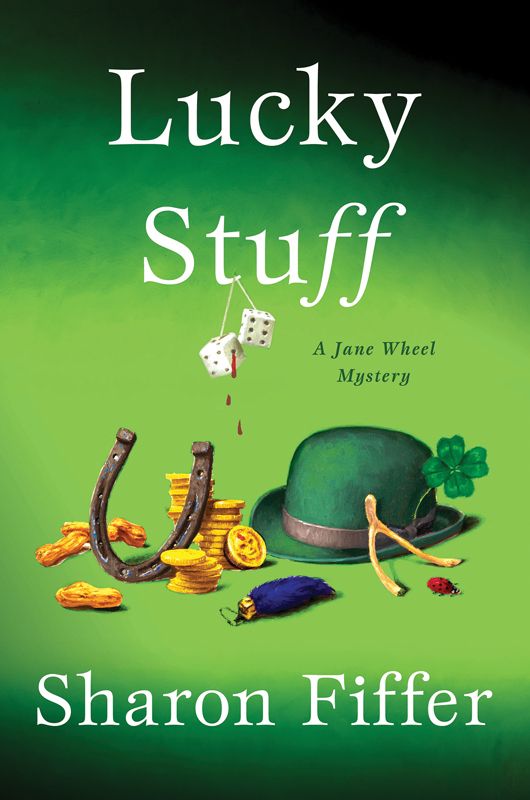

Lucky Stuff (Jane Wheel Mysteries)

Read Lucky Stuff (Jane Wheel Mysteries) Online

Authors: Sharon Fiffer

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way.

Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at:

us.macmillanusa.com/piracy

.

Contents

In what three ways do I count myself lucky?

Kate, Nora, and Rob.

And this book is for them.

Acknowledgments

When it comes to actually producing a novel, a writer probably should thank everyone she has ever encountered—from those who have passed by her office window, wearing a too-big yellow coat, to those couples upon whom she has eavesdropped in coffee shops. In my case, I thank Don and Nellie, proprietors of the EZ Way Inn in Kankakee, and all of those regulars who peopled my life and upon whom I eavesdropped for most of my childhood. Additionally and specifically, in random order, thanks to those who have aided me with answers to my research questions, created a beautiful Web site, read early sections of

Lucky Stuff

and all those who support my storytelling and Jane Wheel’s collecting habits. I present a virtual four-leaf clover to: Dr. Dennis Groothuis, Judy Groothuis, Susan Phillips, Walter Chruscinski and the crew at New Trier Sales, Cas Rooney, Muggs Rooney, Emory Schmidt, Kris Schmidt, Steve Bertrand, Allison Beasely, Betty Schatz, Bill Yonkha. I thank my husband, Steve, for his unconditional support and superlative editing advice; my children Kate, Nora, and Rob and their significant others, Chris, Adar, and Kim, for patiently listening to ideas, paragraphs, pages, and chapters. I thank all of the other Fiffers young and old, for always being supportive and cheering me on. Thanks to my wonderful agent, Gail Hochman, and also Bill Contardi, Lina Granada, Marianne Merola, and Jody Klein at Brandt and Hochman who have helped Jane Wheel find an even larger audience. A four-leaf clover and a lucky horseshoe to my editor Kelley Ragland, who makes the hard work of writing a book the pleasure I always hoped it would be.

1

“I’m sorry,” she whispered, as she struggled to close the lid of the wooden trunk. A middle-aged woman’s face stared up at her. “It won’t be forever … I’ll let you out again,” she promised.

While fighting against the old hinges, Jane Wheel had stopped to admire the milk paint that softened the look of the wood, made the trunk look like whatever it held would be old and precious. As she paused, the relatives being packed away shifted their weight and resisted the lockdown of the heavy wooden lid.

“Aunt Bessie, I am so sorry,” Jane repeated as she smothered Bessie with a small autograph quilt made from men’s suiting fabrics. The houndstooths and tweeds and scratchy woolens might not feel soft to the touch, but they would protect the family members jammed into the wooden box from scratches and breakage. At least Jane hoped the framed photos would be well protected. Aunt Bessie, Uncle Titus, the cousins who worked at the Iowa State Hospital, the 1912 firefighters from Des Moines, the twelve grown men riding on a child-sized train ride somewhere in a leafy park. None of these photos were of people blood-related to Jane Wheel. Aunt Bessie and Uncle Titus were christened on the days Jane gathered them from far-flung rummage sales and flea markets, rescued them from the oblivion of thrift stores and estate sales.

Aren’t we enough for you?

Jane’s ex-husband Charley, would ask.

Of course,

she would answer, beaming at her husband and son, Nick, as she unpacked photo albums and yearbooks and unknown ancestor after unknown ancestor when she returned from Saturday sales. These people needed rescuing, she explained to Charley.

“If I don’t save them, who will?” Jane asked.

And now, as she packed away the faux family, she could point out to Charley, who wouldn’t hear her since he now lived most of the year far from Evanston, Illinois, in Honduras, that the adopted relatives would come in handy to keep her company these days. Nick had been a wonderful companion and it was with great mixed feelings that she celebrated his acceptance at a math and science academy for high school. It was Nick’s dream school—one that would actually sanction time with his father at the dig site if something exciting turned up during the school year. Nick would board at a school with other students like him, brainy and funny and motivated, all on a full scholarship. He had left two weeks ago and Jane still teared up when she thought about his whispered good-bye.

“A text every night, Mom, if there isn’t time for an e-mail, okay? And don’t worry about the house or packing up. I’ll help you do it all at Thanksgiving—Will’s mom said nothing happens in real estate this time of year.”

Nick had hugged her ferociously and for just a second, Jane thought about asking him to give up Lakewood Academy and stick to boring old high school at boring old home with boring old her. But as ferocious as his hug had been, she could see the absolute joy and excitement in his eyes. He was headed to the place he was meant to be.

And Jane? Where was she headed?

* * *

“Trouble. You are headed straight for trouble,” said Nellie, talking out of the side of her mouth as she always did when she thought Don might hear and contradict her. Not that Nellie ever cared who contradicted her.

“I’m headed toward fiscal responsibility,” said Jane. She had caller ID; she had seen that it was Nellie calling. Jane had chosen to answer the phone and had no one but herself to blame.

“You’re a single woman now and your son is off to boarding school. If you sell your house, you’ll be homeless. Hell’s bell’s, Jane, isn’t your life pathetic enough?”

“Thanks, Mom, got to go. Another call—probably someone from the soup kitchen wanting to know if they can deliver my meals or if I’ll be shuffling down to the church basement on my own.”

Jane pushed

END

and her mother’s voice was gone. How she longed for a sturdy Bakelite telephone receiver that she could slam down into an even heavier Bakelite base. Hanging up on someone used to mean something, used to have a kind of sound and fury to it. Ending a conversation with a silent click had no panache and gave Jane little satisfaction. In fact, it was such a quiet ending to the phone call that Jane had no doubt her mother was still talking on the other end, railing about Jane’s decision to sell the house and find a smaller place to live. She would be enumerating all the reasons it was too soon to make a change—the reverse of all the reasons she had enumerated twenty years before when she told Jane and Charley they should not commit to buying the house in the first place.

Buy it they did—for a good price that felt impossible to manage at the time. But the house, the beloved old four-bedroom with charming stone fireplace and ancient hot-water heater and rattling furnace had appreciated—the property’s value had risen up and up to a figure too good to be true. That peak was eight years ago and the figure was indeed too good to be true—in fact, it wasn’t true at all.

Poof

—like a puff of smoke from the working-but-always-problematic stone fireplace, the imaginary profit had vanished and their beloved albeit drafty old house had become one more sad listing on the overcrowded housing market.

“Pack this junk up. Every bit of it,” said Melinda, Nick’s friend’s mom, the realtor who had come over to list the house. “I got phone numbers of people you can hire to come in and have a sale.”

Jane stared at her. Melinda was a sturdy attractive woman whose blazer pulled a little tight in the shoulders, but whose pricey blond highlights and good gold jewelry supported her claim to being a top producer at her realty firm, even in this depressed market.

She was probably a swimmer,

thought Jane, unaware that she was staring at Melinda’s shoulders.

“What? What’s back there?” asked Melinda, turning to look behind her shoulder where she thought Jane was staring. “Oh yeah, you’re going to have to clean up all that luggage. What’s the deal? Packing for a vacation?”

Jane looked at the vintage suitcases stacked behind Melinda’s back. Two drunken pillars on either side of the fireplace, the cases were turned this way and that, brown and red, a few that were striped or plaid and displaying the scars of travel and the tattoos of stickered destinations. They made for interesting storage of old tax information, auction catalogs that Jane used both for reference and her own continuing education as a picker. A brown leather bag with a Bakelite handle contained twenty-five high school yearbooks from the thirties. Jane figured someone who loved cool graphics and vintage photos would buy them in a heartbeat—but that would involve taking them out of the case and actually pricing them for sale.

Melinda had given her a week to clear out the main rooms, offering over and over to help her find a service to do a clean-out.

Last night she phoned Jane to tell her she wanted to bring by a potential buyer in two days.

“I’ve worked with hoarders before,” said Melinda. “I can find you someone to help. Someone who runs estate sales. They know how to get rid of the crap.”

No they don’t. They just bring it all to their homes,

thought Jane.

“What do you say?” said Melinda.

“The house will be ready for showing on Wednesday,” said Jane.

“If you promise…”

“Afternoon. Wednesday afternoon, okay?” Jane could hear Melinda chewing something. She was eating while on the phone. Okay, so maybe Jane looked like a hoarder, but she wasn’t a phone-eater.

“I’ll call you with the time. Get it cleaned out, Jane. If you want to sell this place, clear the decks!”

So, in her best

aye, aye captain

mode, Jane Wheel, Picker and Private Investigator, was spending this warm September evening clearing the decks. She was packing the smalls: the vintage glass and pottery flower frogs that dotted shelves and served as punctuation marks between rows of books in the cases; the McCoy flowerpots that held fistfuls of number-two pencils as well as old plastic advertising pens and mechanical pencils; the small copper vessels in which she had planted bouquets of old pairs of scissors; the Depression glass and mason jars, which bloomed with bunches of wooden and Bakelite knitting needles; the glass apothecary jars that held swizzle sticks and wooden spools of thread and several pounds of old silver and iron and brass keys. A basket of doorknobs stood in the corner and an antique fishbowl sat on the trunk used as a coffee table filled not with koi and guppies, but rather board-game tokens, dice, and orphaned Scrabble letters.

“Am I a hoarder?” Jane asked herself out loud.

Jane sat down on the trunk that now held all those made-up old relatives and gave her living room a long hard look. Stacked cardboard boxes, taped and labeled with a black Sharpie, replaced the vintage luggage stacks. Now packing cases held old flowered tablecloths, napkins adorned with initials not even close to Jane Wheel’s, and tatted doilies, antimacassars and crocheted tea cozies.

One lone black garbage bag sat in the middle of the room. Jane had put it there for any items she came across that she no longer wanted. Movers were coming in the morning to pack up all the boxes and nonessential furniture and driving it to a storage locker in Kankakee—in a facility that Jane’s friend, Tim, used.