Machine Made: Tammany Hall and the Creation of Modern American Politics

Read Machine Made: Tammany Hall and the Creation of Modern American Politics Online

Authors: Terry Golway

For Peter Quinn

For Peter Quinn

CONTENTS

MACHINE MADE

T

he Fourth of July always was a star-spangled day at Tammany Hall. Each year hundreds of New Yorkers made a patriotic pilgrimage to the headquarters of Manhattan’s all-powerful Democratic Party, where they heard politicians from the neighborhood and from all over the United States remind them why their ancestors left behind their homes and families and old identities to come to this new land, to this city where people spoke and ate and worshipped—and voted—in ways that other Americans could barely comprehend.

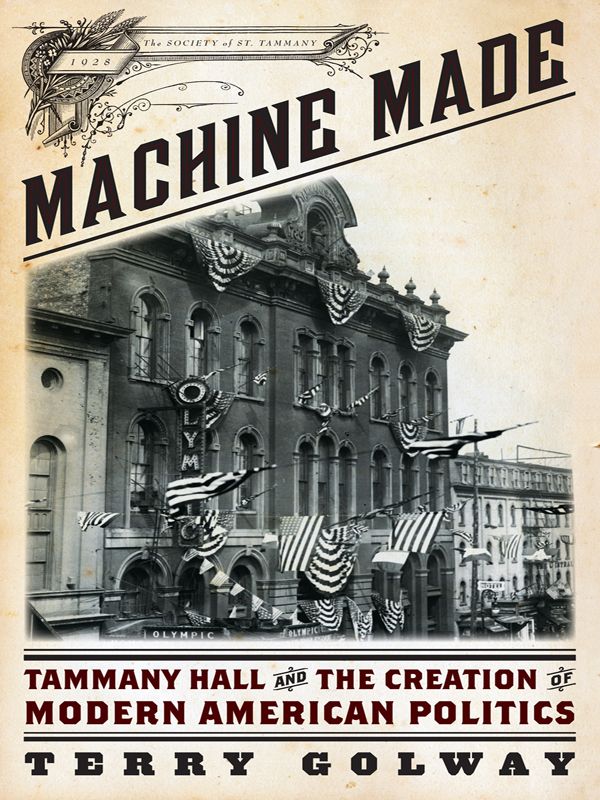

Tammany Hall, the building, was home to Tammany Hall, the controlling body of the Democratic Party of New York County, better known as Manhattan. And Tammany Hall, the organization, knew how to throw a party. There were bands and singers and plenty of red-white-and-blue bunting. Somebody always read aloud the Declaration of Independence—the good parts, anyway—and a couple of honored guests delivered what were called, somewhat forbiddingly, the “long talks.” Invariably these were windy and earnest, civics lessons for those only a generation or two removed from a voyage westward across the Atlantic.

All of this was on the agenda for the Fourth of July in 1929. But that year’s ceremony was unlike any other in the long history of the Society of St. Tammany or Columbian Order, the full formal name of the organization. On that cloudy summer morning, the city’s powerful and mighty assembled near Manhattan’s Union Square to commemorate not just the anniversary of the nation’s independence but also the opening of a brand-new Tammany Hall on Seventeenth Street, just off the bustling square. Generations of New York politicians had come of age in the Hall’s old building on Fourteenth Street, site of the Democratic National Convention in 1868, but the place was too small for an ambitious organization at the height of its power. The new Tammany Hall was built for the ages, with its classical columns, solid brick-and-granite exterior, and the words

Society of Tammany or Columbian Order

etched in stone on the façade. This was the biggest and best Tammany Hall yet, the architectural representation of the organization’s hopes for a long and successful future.

The occasion demanded an exhibition of Tammany at its grandest. The crowds were not disappointed. There, on the stage, was Al Smith, the four-term governor of New York, a Tammany member ever since a saloonkeeper named Tom Foley put him to work for the organization in the early twentieth century. Less than a year earlier, Al Smith, a child of the Lower East Side who dropped out of grade school to support his widowed mother, was the Democratic Party’s nominee for the office of president of the United States. But he was annihilated in the general election because, Tammany loyalists said, he was a Catholic, because he was a New Yorker, because he was a Tammany man, and because he thought it was silly for the government to prevent working people from taking a drink if they wanted one. Al Smith liked a drink himself, and the hell with Prohibition. Most of the people waiting to hear him speak felt the same way.

And there was the mayor of New York, James J. Walker, a Celtic peacock with his movie-star looks and well-tailored suits, an immensely likable man always ready with a quip, a smile, and a handshake. Jimmy Walker was a Tammany man, too, with a fine record of support for social legislation during his years as a state lawmaker in Albany. He was up for reelection in 1929, but he had no reason to worry. Word on the street had it that a Republican congressman and rabble-rouser named Fiorello La Guardia would challenge him in the fall. Few gave the pudgy little man a chance—times were good in July 1929, and the people loved sharp-looking Jimmy Walker even if he spent the night hours in places few would consider respectable. In fact, they loved him because of his defiance of respectability, because he paid no attention to the bluenose moralists who were so quick to divide the world between good and evil, between Plymouth Rock and Ellis Island, between reformer and hack.

From City Hall to national politics, Tammany Hall’s outsize influence on this Fourth of July merited the grander-than-usual ceremonies. Just last November, a member of Tammany’s finance committee, Herbert H. Lehman, was elected lieutenant governor, the first Jewish New Yorker to win statewide office. In the United States Senate, a German immigrant and longtime Tammany member, Robert F. Wagner, was developing a reputation as one of Capitol Hill’s most effective legislators.

Smith, Walker, Lehman, and Wagner were no strangers to the fifteen hundred flag-waving Tammany stalwarts gathered in the new building’s main meeting hall. But the day’s main speaker, well, he was not exactly a frequent visitor. He lived on an estate in the Hudson River Valley, far from the problems and realities of life in the city. He was an aristocrat, a patrician. When he served in the State Senate nearly two decades earlier, he’d made a grand show of his contempt for Tammany. Smith and Walker, who served with him back in those days, called him “Frank.” Now Franklin D. Roosevelt was governor of New York, successor to Al Smith, and he was seated on the flag-bedecked stage, waiting for his chance to speak.