Mad Enchantment: Claude Monet and the Painting of the Water Lilies (12 page)

Read Mad Enchantment: Claude Monet and the Painting of the Water Lilies Online

Authors: Ross King

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Architects, #History, #General, #Modern (Late 19th Century to 1945), #Photographers, #Art, #Artists

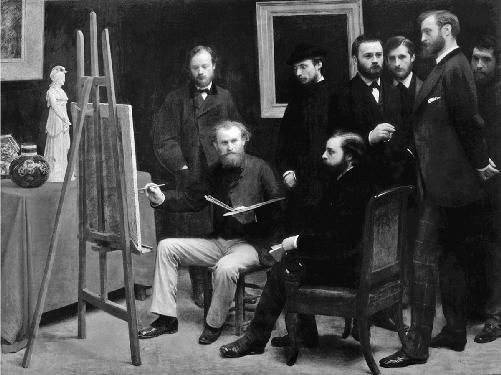

Henri Fantin-Latour’s

A Studio at Les Batignolles

(1870). Monet is on the far right.

The train was swallowed by the Batignolles tunnel and then emerged into daylight to offer a last sight—the Pont de l’Europe, directly overhead—before shunting across the fanwork of tracks and into the Gare Saint-Lazare. Early in 1877 Monet had received permission to set up his easel on the station’s platforms, from where he painted a series

of canvases capturing the clamor of smoke and steam. For one critic, hostile but astute, these works revealed the “disturbing ensemble” of qualities that distinguished Impressionism: “the crude application of paint, the down-to-earth subjects, the appearance of spontaneity, the conscious incoherence, the bold colors, the contempt for form.”

40

It was only fitting that Impressionism should have been so well-defined at this alpha and omega of Monet’s existence, the soaring, sooty building in which so many of his journeys began and ended.

THE FOURTEEN MONET

paintings entering the Louvre had been the property of Count Isaac de Camondo, a Paris-based Jewish financier and collector who originally came from Constantinople, held Italian citizenship and possessed “an extraordinary capacity for making money.”

41

According to one cynical observer, Camondo’s bid for acceptance and respectability had seen him abandon the “slippers and fezzes” of his ancestors for a bowler hat, a subscription to the Opéra, a stable of race horses and a “nobiliary particle.”

42

He also became a connoisseur of paintings, amassing in his lavish apartment in the avenue des Champs-Elysées one of the finest collections of Impressionist works in France. When he died suddenly in 1911 at the age of fifty-nine, he left the entire collection—which included work by Manet and Cézanne as well as Monet—to the Louvre. He also left 100,000 francs for the installation and display of the paintings in a special set of rooms, which in the early summer of 1914 was ready to receive them.

It must have been a triumphant moment for Monet to witness himself and his friends colonizing a corner of the Louvre with paintings that had once been so vigorously despised by the artistic establishment and so controversial with the public. Even Camondo had not been overly keen on some of them: it took a letter from Monet to convince the collector to purchase Cézanne’s

The Hanged Man’s House

. After buying the painting, Camondo, as if to justify this purchase, preserved the letter from Monet in a leather pouch stitched onto the back of the frame.

43

The moment was also one for Monet to remember with fondness—as, perhaps, on the train journey—his own, smaller struggles

and victories. For here were more poignant waymarkers, paintings representing every period of his career and, indeed, of his adult life: from a snow-covered road near Honfleur that he painted as a young man, through scenes of Argenteuil and Vétheuil, to his triumphant Rouen Cathedral paintings (of which Camondo owned four) and a canvas of the water lily pond. A newspaper reported that before his canvases “he had flashes of joy, and he was pleased to recall the year, the date, the smallest circumstances of his works.”

44

SOON AFTER MONET’S

visit to the Louvre that June, a catastrophic thunderstorm struck Paris. A newspaper headline declared: le sol s’effrondre (the ground shatters). Torrential rains, together with “negligence and defects,”

45

caused the Gare Saint-Lazare to flood. Sewers burst and overflowed, the Métro broke down, cracks and holes opened in the streets. One crevasse swallowed a taxi with its driver and passenger; both died. Lightning strikes killed a team of railway workers and sent debris from rooftops cascading into the streets. Gas lines exploded in flames, with a particularly violent detonation in the rue Saint-Philippe-du-Roule blasting a hole twenty-five yards deep that engulfed an upholstery shop. An ox fell into another fissure in the boulevard Ney, while nine horses working underground at the Porte de la Chapelle drowned when water ten feet deep flowed into the railway tunnel. Yet one journalist, venturing out that night to watch the rescue efforts of the frantic firefighters in their acetylene headlamps, was astounded to see lights blazing and music blaring in a building in the rue La Boétie where couples, cheerfully oblivious to the destruction everywhere around them, danced “languorous waltzes and voluptuous tangos.”

46

It is hard not to see in this carefree waltzing on the edge of the yawning abyss what the journalist could not: a parable of France in the summer of 1914—an insouciant, fun-loving world about to be engulfed by tragic events. Later, people would look back nostalgically at the prewar years as a golden age of gaiety and joyous innocence, as the period of blissful nonchalance and elegant artistry that gave rise to the German expression “as content as God in France” and much later, after it had all

disappeared, to the French expression

la belle époque

. The belle époque was a retrospective construction, to be sure, but an image of this land of soon-to-be-lost content—a contemporary portrait of the delightful enchantments of what Parisians themselves called

la vie douce

(the sweet life)—had been offered to readers of

Le Figaro

exactly one year earlier. In June 1913 one of the newspaper’s journalists asked a troop of forty-seven Boy Scouts visiting from San Francisco their opinions of Paris. The Scouts had been impressed by the Eiffel Tower and the gargoyles on Notre-Dame but also by the fountains and public gardens, the tree-lined boulevards, and the outdoor cafés where, while having a drink, one could watch people passing in the streets. They admired the red trousers of the French soldiers, the beards on the young men (who, hats in hand, sometimes embraced one another), the long loaves of bread, the extraordinary number of automobiles (there were six hundred car manufactories in Paris alone), and naturally “the fine young ladies of fashion,” who, the young Scouts observed with awed incredulity, smoked cigarettes in the street.

47

This image of Paris, with its boulevards, gardens, cafés, and women of fashion, was that of Monet and the Impressionists: the happy world of beauty and elegance, of casual everyday leisure, that they had brought to life and commemorated under their brushes. Monet’s garden, for some, as well as his paintings of his garden, were as much a part of the visual vocabulary of Paris as the Art Nouveau entrances to the Métro stations and the dancers at the Folies-Bergère. “When I think of the beautiful times of peace,” a novelist turned soldier would write to Monet from the trenches barely eight months later, “I see often the gorgeous garden and the large dining room at Giverny.”

48

Monet’s gorgeous garden appears to have come through the great storm of June 1914 more or less unscathed. He noted the “terrible weather” in a letter to Charlotte Lysès, but two days after the deluge he informed another friend that he was in “a fever of activity” and had no time to leave home. “My work before everything,” he wrote in a declaration that might have served as his manifesto, and one on whose resolution he would need to call many times in the years to come.

49

Several weeks later he wrote two more letters: one to a certain Madame Cathelineau, to whom he offered to show his water lilies in their full June bloom; and the other to one of his picture dealers in Paris, Paul Durand-Ruel. He informed Durand-Ruel that he was back at work, that his eyesight was better, and that “everything goes well.”

50

The date of these remarkably upbeat letters was June 29. On that same day the front pages of all the French newspapers were reporting the assassination in Sarajevo of the Austrian archduke Franz Ferdinand.

GEORGES CLEMENCEAU HAD

not been one to dance on the edge of the abyss. He saw and feared the gathering storm. In March, while unveiling a statue to an Alsatian politician in Metz, he had declared of Germany: “Her fury for the leadership of Europe decrees for her a policy of extermination against France. Therefore, prepare, prepare, prepare.”

51

It was an audacious speech considering that Metz had been part of the German Empire since 1871. Throughout the first half of 1914, his daily editorials for his latest newspaper,

L’Homme Libre

, deployed his considerable rhetorical power to warn against what he called “German Caesarism.” All the forces of the German Empire were, he wrote, “advancing in a formible array of coordinated activities toward the goal of world domination—which will be peaceful if the world resigns itself to submission, but violent if resistance is given.”

52

He deplored the poor state of French munitions and the fact that the Germans had 3,500 heavy guns compared to France’s paltry 300. He advocated an extension of compulsory military service from two years to three, the better to maintain a large, well-drilled army. When soldiers in the eastern garrisons mutinied at this proposal, he published a pamphlet asking them: “While you throw away your arms, do you not hear the clatter of the field-guns on the other side of the Vosges?”

53

Clemenceau’s editorial for June 23 had declared: “There is no point in denying that Europe lives in a state of permanent crisis.” That crisis became ever more acute with the assassination of Franz Ferdinand. Yet even Clemenceau could not foresee how events would unfold. Two days later his editorial on the “appalling tragedy in Sarajevo” bore the title

“Into the Unknown.” The leader of the French socialists, Jean Jaurès, was less hesitant to predict where events might lead. Jaurès was the only politician in France with the charisma, intellect, and rhetoric to match Clemenceau, to whom he was a considerable and inveterate opponent. If Clemenceau was the most brilliantly forceful writer in French politics, Jaurès was by far the most spellbinding orator—according to some, the greatest of all time.

54

In July 1914, Jaurès turned his formidable oratorical skills against French involvement in the “wild Balkan adventure,” believing that war could still be averted. He exhorted his audience in a speech in Vaise, near Lyon, on July 25: “Think of what that disaster would mean for Europe...What a massacre, what destruction, what barbarism!”

55

Much of France was, however, distracted from issues of Serbian politics and impending massacres by l’Affaire Caillaux—the murder trial of Henriette Caillaux, the second wife of Joseph Caillaux, formerly Clemenceau’s minister of finance and, from June 1911 to January 1912, prime minister. In March 1914 the editor of

Le Figaro

, Gaston Calmette, in a campaign against Caillaux, published some of his private correspondence—including letters written to Henriette while he was still married to his first wife—as proof of his having used dishonourable means to achieve personal goals. “He is unmasked,” Calmette triumphantly announced. “My task has been accomplished.”

56

Madame Caillaux accomplished her own task three days later, entering Calmette’s office in the rue Drouot and discharging six shots from the Browning automatic pistol concealed in her fur muff. She came to trial for his murder in July.

As Europe teetered on the brink, far more ink was devoted to the trial of Madame Caillaux than to the worsening political situation. One newspaper,

L’Écho de Paris

, cleared its pages of virtually all other news. Even the front page of

L’Homme Libre

offered its readers the smallest details of the case, including the fact that Madame Caillaux, wearing a black dress and a hat of black straw, sustained herself on the first day of her trial by eating a luncheon of jellied eggs and salt-marsh lamb washed down with a bottle of Évian water.

57

After a trial that drew in two former prime ministers, along with various cabinet ministers past and present, she was acquitted on July 28. The announcement came only hours before

Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia and began bombing Belgrade. It came three days before another shocking event: the assassination of Jaurès by a French nationalist in a café in the rue Montmartre.

On the following day, August 1, the general mobilization order arrived by telegram at the Assemblée Nationale, where it was immediately put on display. Outside, in the newspaper kiosks along the quai d’Orsay, Clemenceau’s headline in

L’Homme Libre

declared: the race into the abyss. Two days later, at six fifteen

P.M.

, as thunderstorms shook Paris and pelted the streets with rain, Germany declared war on France.

58