Mad Enchantment: Claude Monet and the Painting of the Water Lilies (48 page)

Read Mad Enchantment: Claude Monet and the Painting of the Water Lilies Online

Authors: Ross King

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Architects, #History, #General, #Modern (Late 19th Century to 1945), #Photographers, #Art, #Artists

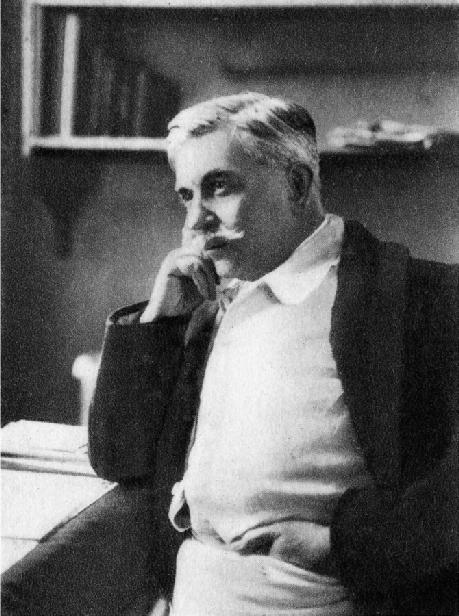

Dr. Charles Coutela, Monet’s eye doctor

Coutela had been placed in an extremely difficult situation, and he was increasingly reluctant to play ball. He composed a long reply to Clemenceau from a “noisy café” in Saint-Flour. (This location, in the beautiful and remote Auvergne, more than three hundred miles south of Paris, was probably best kept from Monet, who already felt that the doctor’s leisurely peregrinations kept him from being at his beck and call.) Coutela was fast becoming exhausted by his celebrity patient with his special demands and perhaps unrealistic expectations: a replay of the experiences of the unfortunate Louis Bonnier. “For the life of an ordinary man,” Coutela wrote to Clemenceau, “the result, it seems to me, is sufficient. But Monsieur Monet needs vision for something more

than ordinary life...His distance vision is good enough for the everyday citizen but not for such a man as him.” In other words, the operation had been a success, but unfortunately the painter had died. In answer to Clemenceau’s question, he believed an intervention on the left eye was absolutely necessary. However, Coutela had little relish for tackling the job himself. “Personally, Monsieur Monet has made me go through such agony that I decided to pass on this second eye.” Yet he was willing to reconsider, he told Clemenceau, because Monet is “such a brave man” and because he liked him “despite his flashes of anger.”

76

Clemenceau therefore wrote to Monet in the middle of September, telling him bluntly: “You will not be able to finish the panels without the second operation.”

77

Monet was equally blunt in return: “I want to tell you frankly and after mature reflection,” he wrote on September 22, “that I absolutely refuse (for the moment at least) to undergo an operation on my left eye.”

78

THE ONE THING

that could have persuaded Monet to undergo an operation on his left eye was the testimony of an artist successfully delivered from a similar plight. So it was that he wrote to the painter Paul-Albert Besnard. The seventy-four-year-old Besnard was one of the Immortals, a much-decorated artist who had served as director of both the Académie Française in Rome and the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. Extremely well connected both socially and professionally, Besnard was known to both his fellow Immortals and, as the organizer of a recent exhibition, the Salon des Tuileries, to many of the younger generation of painters as well, many of whom had been his students in Rome and Paris. It was this social omniscience, it seems, that solicited the letter from Monet, who appealed to an “old friendship” with Besnard.

79

“My dear Besnard,” Monet began. “I have a favour to ask of you.” After outlining his recent medical history—three cataract operations since January, their less-than-satisfactory outcomes, the possibility of another—he asked if Besnard knew of an artist who had successfully undergone a cataract operation to regain his color perception. He was asking Besnard, he said, because he could not trust the doctors, with

their conspiracy of silence, to be candid: “The oculists close ranks and keep secret anything that suggests a failure.”

80

Besnard failed to produce evidence of a successful operation. However, Monet knew the plight of Mary Cassatt, whose eyesight began to fail around the turn of the century, when she was in her mid-fifties. She had been diagnosed with cataracts in both eyes in 1912, the same year that Monet received his own diagnosis. By 1923 she had undergone five operations, all without the slightest improvement. René Gimpel, who visited her in the spring of 1918, following her first three operations, observed: “Alas, the great devotee of light is now almost blind.” He reported her sorry condition to Monet a few months later “and I sensed an old man’s indifference.”

81

Monet’s indifference might have been explained by the fact that in 1918 his eyesight was causing him fewer problems. In the event, he appears not to have approached Cassatt for advice, despite mutual friends such as Gimpel and the Durand-Ruels. The failure of her operations would have done little for his confidence, and she certainly could not be counted among the success stories that he was desperately hoping to find. In the absence of such evidence, he was more determined than ever not to submit himself yet again to Dr. Coutela’s knife.

By the end of September, fearing for the fate of the panels and losing all patience, Clemenceau started exerting pressure on Monet to undergo another operation. Letters flew back and forth between Belébat and Giverny, with Clemenceau advocating further surgery and Monet replying with letters that were, in Clemenceau’s words, “nothing but one long groan.”

82

In the midst of this impasse, Monet did what he always did when he reached the deepest fathoms of a crisis: he took up his brushes and began painting. He was assisted by a new pair of German spectacles that arrived in October. “To my great surprise,” he informed Coutela, “the results are very good. I can see green and red again and, finally, a feeble blue.”

83

As he began working frantically toward his April deadline, determined to finish the panels on time, Clemenceau was relieved and delighted. “How happy I am, my dear friend, to know that you are hard at work! That’s the best possible news...Your good ship

sails again. Navigate well. It’s foggy here, but the important thing is to have the sun in your heart.”

84

Two weeks later, in the middle of December, Clemenceau and Coutela made their way to Giverny to present Monet with yet another pair of spectacles. On their return to Paris they were injured in a road accident when the Rolls-Royce, swerving to avoid an automobile braking ahead of them, collided with a tree. Clemenceau, who always sat in the front seat, suffered lacerations to his face, lost a lot of blood, and was taken with Coutela, likewise injured, to the hospital in Saint-Germainen-Laye. They were released that evening after receiving stitches. Clemenceau wrote jovially to Monet that it was a “poor excuse for an accident” and that he would try to do better next time. A day later he signed off another letter—unwisely tempting fate—“Until the next catastrophe.”

85

CHAPTER NINETEEN

THE SOUL’S DARK COTTAGE

AT ELEVEN FIFTY-EIGHT A.M.

on September 1, 1923, a deadly earthquake struck the Kanto region around Tokyo. It was followed by raging fires that turned the imperial capital into, in the words of an eyewitness, “a sea of flame.”

1

As many as 140,000 people perished in the disaster. Among the dead, according to French newspaper reports, was Kojiro Matsukata.

2

Rumors of the tycoon’s death turned out to be greatly exaggerated, but the dreadful scale of the destruction wreaked on one of France’s allies—a nation “that was by our side in our days of struggle,” as the Chamber of Deputies somberly declared

3

—spurred the French into sympathetic and charitable actions. Prime Minister Millerand sent his condolences to Emperor Yoshihito, while the mayor of Verdun, hitherto the world’s most famous devastated city, sent his condolences to the Japanese ambassador. A “

gala japonais

” was held at the Hôtel Claridge, aid parcels were collected for shipment to Japan courtesy of a women’s group headed by Madame Poincaré, and box office receipts from art exhibitions and cinematographic performances were allocated to disaster relief. The Théâtre du Colisée showed a series of documentary films on the principal sights of Japan, with the receipts of its matinee performances earmarked for the many thousands of injured and homeless.

Few could have been surprised, then, when early in January 1924 an exhibition for the benefit of the victims of the earthquake opened at the Galerie Georges Petit in Paris. Curated by Matsukata’s friend and advisor Léonce Bénédite, it was entitled

Claude Monet: Exhibition Organized for the Benefit of the Victims of the Catastrophe in Japan

. The exhibition featured some sixty of Monet’s paintings, including

Women in the Garden

as well as all of those owned by Matsukata and destined for the

Art Pavilion of Pure Pleasure. The exhibition was certainly a timely and appropriate gesture, as a reviewer for

Le Rappel

commented: “Claude Monet has many admirers throughout the world, but especially among Japanese artists. Was he not one of those who revealed to us the beauty and originality of the painters and engravers of the Far East, of whom he was a devoted worshipper?”

4

The only person surprised by the exhibition, it turned out, was Monet himself. “Just think,” he fumed to Geffroy, “this Bénédite said nothing to me about this exhibition, he didn’t even consult me, as if I no longer mattered. What an oaf.”

5

Learning of the exhibition only a few days before the opening, he immediately appealed to Clemenceau, who in turn appealed to Paul Léon. Monet was outraged by the fact that, in loaning the paintings from Matsukata’s collection, of which he was custodian, Bénédite proposed to put on public display two large decorative panels, examples of the Grande Décoration. “The plain fact is,” Monet wrote to Bénédite, “that you failed in your duty as soon as you decided to stage this exhibition without first informing me. Not that I would have refused, of course, but above all I would have begged you, for the reasons that you know, not to exhibit the two decorative panels.”

6

Monet’s reaction was quite understandable. One of the decorative panels in question was the fourteen-foot-wide wide canvas that Matsukata had purchased on his visit to Giverny in 1921, the other the six-and-a-half-foot-square

grande étude

,

Water Lilies

, for which he reportedly paid 800,000 francs a year later. A showing of such paintings would preempt the opening of the Musée Claude-Monet, which, if all went well, would take place in the spring. Monet was no doubt especially anxious for the removal of the larger of the two paintings because it was a study for (even perhaps a version of) the massive composition,

Reflections of Trees

, destined for the second room of the Musée Claude-Monet: a dark and even disturbing vision whose unsettling impact at the Orangerie would be offset by this rather casual preview. Adding insult to injury was the fact that this large canvas had been hung upside down—a gesture that, however unintentional, may have brought back bitter memories of how, when the bankrupt Ernest Hoschedé’s collection was auctioned in

1878, some of the Impressionist paintings were deliberately hung upside down to emphasize their supposed unintelligibility.

7

Intervention by Paul Léon, Bénédite’s superior, saw the removal of the fourteen-foot-wide painting from the exhibition, but the other work, the 1916

grande étude

, remained on show.

Readers of the journal

Revue des Deux Mondes

were likewise offered a sneak preview of the Grande Décoration. In the middle of January, the art historian Louis Gillet came to Giverny to visit Monet and see his paintings. Two weeks later, he whetted his readers’ appetites for “

la grande décoration

on which Claude Monet has been working in secret for eight years.”

8

It would be, he claimed, Monet’s major work, more spectacular even than the landmark waterscape exhibition. “It had seemed,” he declared with reference to this 1909 show, “that the art of painting could go no farther.” But of course Monet had dared to go even farther. During the war, Gillet informed his readers, the master “resolved to risk more than ever, and to pit his Impressionism against the great monumental art of Delacroix and Puvis de Chavannes.” He described Monet’s increasingly solitary life, his shredded canvases, and how, in order not to lose a minute, he summoned the local barber to cut his hair as he worked at his easel. Gillet then dramatically announced that the massively ambitious project had been completed and soon could be seen in all its glory: a “vast circle of dreams” that would “encompass with its magic touch the halls of the Orangerie.”