Madam (7 page)

Authors: Cari Lynn

Finally, Peter offered up his thoughts. “Lobrano was makin’ a racket out there,” he said, then quickly busied himself again with the hearth, so as not to face Mary. “I could hear how he was talking at you.”

Shame landed like a stone in Mary’s stomach. Out of respect, they usually avoided such talk. They all knew her work was crude, and there was no reason to go and speak outrightly about it. They talked of her work the same as they did of his selling potatoes in the market or of Charlotte’s seamstress work. Just jobs that put food in their bellies and shoes on their feet and kept them in clothes that weren’t too tattered, which was more than a lot of folks could claim.

But Peter continued on, troubled in a way Mary couldn’t remember seeing him. “What’s gonna happen when there’s a child around?”

“Why are you harpin’ like this, Peter? Things’ll be different soon enough.”

“Different how?” he demanded.

Mary brought the cup of grits to her lips and let a warm, buttery mouthful slide down the back of her throat. She could feel Peter’s eyes on her and had noticed the deepening purplish shadows, just like when he was a child.

“Lobrano’s gonna get me my own crib,” she said staunchly, and as the words hovered in the air, she wanted so badly for them to be true.

Peter’s shoulders drooped, and he stared blankly into the flames. “You keep tellin’ that to yourself,” he mumbled. “Might as well tell it to a fence post.”

Mary ignored him. All she wanted was to savor the last mouthfuls of grits and enjoy the peace of the night with no one grabbing at her, no one wanting anything from her.

But, uncharacteristically, Peter wasn’t going to let their talk taper off. He turned to face Mary. “You keep tellin’ that to yourself,” he said again, only this time his voice rose above their respectful hush. It also wasn’t like Peter to raise his voice, especially not to his older sister. But he was staring at her squarely, his jaw quivering. “You gonna tell that to the baby when it comes?”

Caught off guard, Mary recoiled. She could feel her own temper rising at his insolence. It was she who’d been caring for him since he was born, and she who brought in most of the money; he did honest work, but a whore earned more any day of the week than a potato seller. She’d already held her tongue enough times today, and, even more, what was Peter wanting from her anyway? She was doing everything she could to save money for his baby.

Just as she was about to spit back a sharp word or two, a groan arose from Charlotte, who shifted uncomfortably in her sleep. Mary swallowed back the scolding, not wanting to wake her. She gave a smoldering look in Peter’s direction. He deserved some reprimand for what he’d said. And then it occurred to her—her little brother was a worried father, that’s what this was about. It could be any day now, and the panic of bringing a baby into this world, especially when their own mother . . . No, no, she stopped herself, she mustn’t go there. No need to rile up her own tensions any more tonight.

“You must be tired, Peter,” she said. “Stop worrying and let me be.”

Chewing on his lip, he moved to Charlotte, tightening the blanket around her and softly sweeping the hair from her face. He was a gentle soul toward his wife, and it made Mary’s heart ache to watch his tenderness.

He settled himself into the rocking chair and closed his eyes. “You’ve always been so smart, Mary. Much smarter than me. But when it comes to Lobrano, you hide your smarts. Did you forget? You’re Josie.” He gave a little smile, but his face still seemed bereft. “You’re the conductor.”

Mary knew the passage by heart from their growing-up years. It was a story in a magazine called

The Nursery

, which a man friend of Mama’s from a place called Boston had pulled from his satchel and given to little Mary. Having just learned to read—Mama made sure her children spent some time in the schoolhouse—Mary read to her brother every night. While Mama was gone working, Mary and Peter would huddle together on the cot they shared and try to cover with giggles each scary creak and crack of their dark, empty shack. Out of all the lines of verse and short stories in that magazine, Peter’s favorite was about Josie the conductor. He’d ask for the story over and over again. He’d call out, “All a-boarrrd” when it came to the part where the train left the station with the passengers in two blue cars, the US mail in the green car and Josie commanding the big red engine.

“I ain’t smarter than you, Peter,” Mary said, knowing full well that wasn’t the point he was after.

“Oh, Mary. Lobrano’s scared of you, can’t you see that? He always has been. I ain’t saying this to be nice. I had a long day, and I’d rather be sleeping than sitting here flattering my sister. I’m saying it ’cause it’s true. He’s scared of your smarts.”

Mary had no response. She’d never thought of herself as smart. She thought a person had to be fully schooled to be smart, and she hadn’t even completed primary school. Although, she could read and write just fine, which was more than most whores could do.

“Get some rest,” Peter whispered to Mary, and she watched as he gingerly crawled into bed, careful not to bother his wife. Mary pulled the curtain that divided the one room, offering a pretense of privacy, and prepared her bath.

C

HAPTER THREE

S

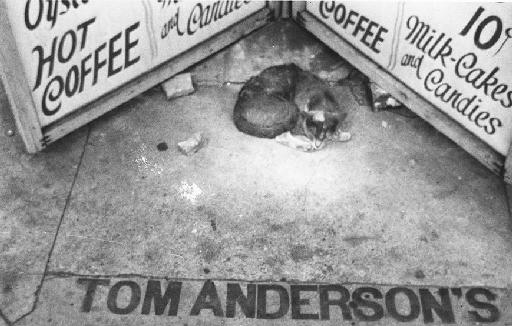

nitch, eyes wide as saucers, stared at rows upon rows of money. He’d never seen so much money—fives, tens, twenties even, and dozens of stacks. Still out of breath from having raced through Venus Alley to Anderson’s Saloon, his chest heaved as he watched Tom Anderson order the cash. He seemed almost hypnotized as Anderson methodically counted and stacked the bills, his chunky gold and jeweled rings sparkling as he carried the piles of money across the room to a walk-in safe.

A dashing, mustachioed dandy, Tom Anderson was the unofficial mayor of the Underworld, and here, in a mahogany-paneled room in the back of his eponymous saloon, he shrewdly and lucratively—very lucratively—ran Venus Alley.

Snitch wondered what a stack of those bills would feel like to hold, and he had to bite his tongue to keep from asking Mr. Anderson if he could touch one. Wouldn’t it be something, he thought, just to walk down the street with one of those bundles of cash tucked into his shirt pocket! No, he decided, not in his shirt pocket, that would be too obvious. What’s that lump there, Snitch, ya growin’ a teat? That’s what all those nosy whores would say. No, he’d have to divide the stack and line the inside of each of his shoes—he’d be inches taller walking around on that cash. It’s true, y’all, he’d report, money does wonders for a man’s stature!

Anderson’s baritone voice snapped Snitch from his reverie. “You sure there isn’t some small trifle of a detail that you’re forgettin’ to mention, Snitch?”

Glassy-eyed, Snitch looked up. “Oh no, Mistah Anderson, ain’t nothin’ to forget. I’m just reportin’ what all I saw. He was just lyin’ there, fat-assed and dead as a dodo.”

Anderson made a dubious face. “A dodo? You even know what that is?”

Snitch shrugged. “Somethin’ awfully dead.”

Anderson chuckled to himself. Didn’t this child know fear? he wondered. He was used to people feeling uneasy around him, but Snitch seemed unaffected. To most everyone else, Anderson cast an intimidating presence. Six feet tall with a solid, robust frame, he always appeared impeccable, from his exquisitely tailored suits to his sable-colored mustache groomed into perfect curlicues. His dark, penetrating eyes were attuned to every detail—they could charm you or shame you. But most notable was his reputation: he was a man who always got what he wanted, no matter what it took.

Tonight’s unfortunate incident of a dead body on Venus Alley wasn’t sitting well with Anderson. The others in the room, his two henchmen, Tater and Sheep-Eye, were too dim to surmise the possible impact—but not Snitch. Anderson knew how cagey Snitch was, and he watched the boy with a precise eye. Watched him staring down the table of cash like a lizard at a fly, figuring the boy might even be snaky enough to have a projectile tongue, or at least figure how to use his own to nab a bill if he thought no one was looking.

“Someone refresh my memory,” Anderson said, “as to how we disposed of the last heart attack.”

Tater and Sheep-Eye groggily looked at each other. They were as gruesome as Anderson was handsome. Both bulky with muscle, they also had the swollen, crooked features and jagged, raised scars of men whose faces had been on the receiving end of too many fists. They’d flanked Anderson for years, dealing with the unsavory issues that tended to arise when one ruled the Underworld.

“I recollect we’s dumped him in the Pontchartrain,” Tater said.

Sheep-Eye nodded. “I recollect that too.”

Snitch piped up, “Nothin’ was in his pockets, Mistah Anderson. Ain’t found no money for my troubles.”

Anderson cast a weary sideways glance. “Ain’t subtle, are ya, Snitch?”

Snitch twisted up his face, another word out of his reach. “Don’t rightly know, Mistah Ander—”

“Well, you ain’t,” Anderson said. Deciding he might as well have a little fun with the boy, he took a dollar from a pile, watching Snitch’s eyes narrow in. “Now, Snitch, you gonna tell me which of my properties this dead trick came out of?” He dangled the dollar, and Snitch, nearly cross-eyed, followed its every move.

“Somewheres on Venus Alley,” Snitch insisted. “I promise I didn’t see nothin’.”

“So the body just appeared in the middle of the road?” Anderson snarled, lifting the dollar higher—maybe the more Snitch tilted his head, the more of a chance something might leak out of it. But Snitch held defiant, the best little liar on Venus Alley. Like taunting a dog with a steak, Anderson teased him a few seconds more, until he finally relented, tossing the boy the dollar and waving him off.

“Thank ya, Mistah Anderson!” Snitch gushed. “You know I do my best for ya!” He gleefully scampered out.

Anderson shook his head, then turned back to his henchmen. “Boys, this ain’t good. The City Council’s got a stick so far up its ass they can taste wood. One misstep like this may be all it takes for them to release their holy fury.” He leveled his gaze. “You ever seen holy fury, boys?”

Tater and Sheep-Eye vigorously shook their heads like children hearing a ghost story.

Anderson’s eyes grew large with warning. “Holy fury is the worst kind.”

He counted off several bills, handing a few to Tater and a few to Sheep-Eye. “Go to Venus Alley and get that body outta there and into the icehouse quick and quiet. By half past I want no sign that sorry bastard ever stepped a fat foot on the Alley. Then I want you to find out who he was. Someone from the bayou? Was he a son of a bitch from money? Is a posse gonna turn up lookin’ for him? Does the whore he was riding need to end up floatin’ down the Pontchartrain? Only pay for solid information, and for fuck’s sake, if Snitch is the only one you can find who’s seen something, hang him by those skinny ankles till he talks.”

Tater and Sheep-Eye obediently piled out. Glad to see them go, Anderson closed the door behind them, then shut the safe and spun the lock. Damn whores—this wasn’t what he wanted to spend the evening thinking about. He reclined into a buttery leather armchair and stretched his neck from side to side.

This mahogany back room was his haven, more meaningful to him than any room in his own house. To look around was to know Tom Anderson: on the wall hung a framed eighteenth-century map of the Louisiana Territory, entitled “La Louisiane.” Several bottles of fine, aged Scotch waited on a hutch. A shelf of books announced interests of capitalism, politics, and persuasion:

The Wealth of Nations

,

Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant

,

The Federalist Papers

, Plato’s

Republic

, and

A Treatise of Human Nature

.

Reaching for his velvet-lined cigar box, Anderson removed a fat J.C. Newman Diamond Crown and dragged it under his nose, inhaling heavily; for a moment, he rested there, savoring the ritual. Then he cut the tip and hovered a silver lighter engraved with his initials, puffing until the cigar was lit. He leaned his head back as he exhaled.

He’d smoked his first cigar when he was twelve. That cigar was the only thing he’d ever stolen from his father, even though he’d detested the old man. He was born and raised in Atlanta, where, as far as he knew, the Andersons still resided on a sprawling cotton plantation originally cultivated by his great-grandpop. If there were such a thing as Atlanta aristocrats, the Andersons were them.

Tom was an only child, for his mother had taken ill during his birth and never fully recovered. Spending most days in her sickbed, she secretly blamed her son for stealing her health; it was Tom’s father who blamed him outrightly. The household tended to be painfully quiet, and Tom spent his childhood hushed and shooed, away from Mother, who was always resting, and away from Father, who was creased with worry over his ailing wife. Try as he might to be obedient and helpful, and never wanting to cause more strain than he apparently already had, Tom was nonetheless treated as a bother, a nuisance, and—perhaps worst of all—he was overlooked.