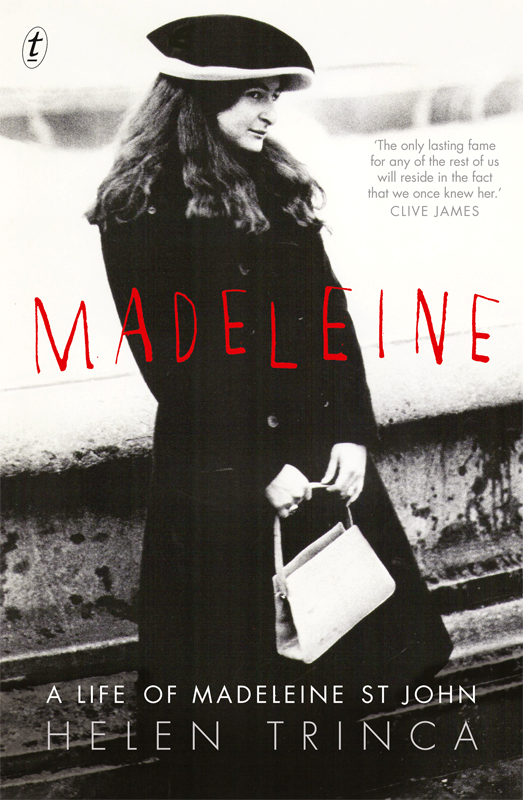

Madeleine

Helen Trinca has co-written two previous books:

Waterfront: The

Battle that Changed Australia

and

Better than Sex: How a Whole

Generation Got Hooked on Work

. She has held senior reporting and editing roles in Australian journalism, including a stint as the

Australian

's London correspondent, and is currently managing editor of the

Australian

.

A LIFE OF MADELEINE ST JOHN

HELEN TRINCA

Photographs supplied by: Felicity Baker: Madeleine and Chris; Madeleine at Swinbrook Road; Madeleine with Puck, by Felicity Baker. Florence Heller: Madeleine in London, by Frank Heller. Nicole Richardson: Feiga and Jean Cargher; Sylvette in Sydney; Ted and Sylvette with John and Margaret Minchin; Ted with baby Madeleine; Madeleine with Sylvette and Ted; Madeleine and Colette âsmiling for the camera'. Deidre Rubenstein: Madeleine with Swami-ji.

Sydney Morning Herald

: âThe Octopus' at

Honi Soit

, by B. Newberry/Fairfax Syndications. Madeleine in 1998, by Jerry Bauer. St John family, by Margaret Michaelis. Cover photo: Madeleine in the snow in Trafalgar Square, 1968, by Daniels McLean.

The Text Publishing Company

Swann House

22 William Street

Melbourne Victoria 3000

Australia

Copyright © Helen Trinca 2013

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright above, no part of this publication shall be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

First published by The Text Publishing Company, 2013.

Cover and page design by W. H. Chong

Typeset by J&M Typesetters

National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication

Author: Trinca, Helen.

Title: Madeleine : a life of Madeleine St. John / by Helen Trinca.

ISBN: 9781921922848 (pbk.)

ISBN: 9781921961137 (eBook)

Subjects: St John, Madeleine, 1941â2006.

Authors, AustralianâBiography.

Dewey Number: A823.3

for Ian Carroll

1946â2011

CONTENTS

IntroductionâA Night to Remember

5Â Â Â Flower Girls for a Stepmother

6Â Â Â Sydney Uni and the Octopus Girls

18Â Â A Moment in the Sunshine

19Â Â The Essence and the Booker

23Â Â Friendships Lost and Found

INTRODUCTION

A Night to Remember

The Booker Prize dinner in London's Guildhall is a flash affair. The wine flows as hundreds of publishers, authors, agents and critics crowd around their tables to hear which book has won the award for the best novel of the year from the British Commonwealth and Ireland. There is glamour, gossip and apprehension. The Booker brings prize money, but the real value comes from the cachet, which translates to sales and profile. Someone's life will change tonight.

In October 1997, a birdlike woman, Madeleine St John, was perched at one of the Guildhall tables. Her third novel,

The Essence of the Thing

, was on the shortlist. St John had struggled for decades to survive in Londonâshe was financially and physically stretched, already suffering from the emphysema that would claim her life. Scarcely known by the literary critics, she had enjoyed plenty of attention since the nomination, with journalists trooping up the stairs to her Notting Hill council flat for interviews.

At home, a surprised media reclaimed her as the first Australian woman shortlisted for the Booker. St John was furious. She had spent her life reinventing herself and avoiding the Australian tag, even taking British citizenship in 1995. All but one of her novels catalogued the lives of inner London's professional class, not the bush and the beach. The last thing she wanted to be was Australian. But as the Channel 4 cameras panned across the Guildhall and millions of Britons watched the event live, Melvyn Bragg announced St John was from Australia.

The bookmakers had her as the outsider at eight to one, but writer A. S. Byatt told Channel 4 that

The Essence of the Thing

was the novel that excited her above the others. St John was nervous but hopeful of what the night would bring. Winning the Booker would be a vindication of the choices made a lifetime ago, proof to the extended St John clan, whom she loved and loathed, that she had succeeded in spite of them. The sweetest victory of all would be over her father, Edward St Johnâpolitician, barrister and pillar of the community. Ted had died in 1994, but his daughter still had scores to settle.

Madeleine St John was a war baby, conceived after her father signed up for service and born five months after he was shipped out with the AIF to Palestine. Ted St John did not know that his wife was pregnant when he left. Indeed, Sylvette St John appeared to have been unaware she was carrying a child until five months into the pregnancy.

1

She scarcely had time to get used to the idea before her baby was born, two months premature, at 8.40 p.m. on 12 November 1941, at the King George V Memorial Hospital for Mothers and Babies in Sydney's inner-suburban Camperdown. The baby weighed just 4lb 2oz. When news of the birth reached him in the Middle East, Ted knocked on the door of a convent of French nuns in Bethlehem and bought from them a tiny lace collar as a gift for his firstborn.

2

Back in Sydney, Sylvette, who had come to Australia from Paris just before the war, registered her daughter as Mireille. Mother and baby spent a few days at a specialist Tresillian centre, the custom after a premature birth, before going home to the flat at 22a New South Head Road, Vaucluse, which Sylvette shared with her parents and her teenage sister Josette. It was not quite the perfect start for the baby girl: an absent father and a mother who had been in denial for months before her birth and who seemed unable to decide on the name. Mireille remained on her birth certificate but she was called Madeleine almost from the start.

3

Yet Madeleine's babyhood was not unusual. Normal life had been on hold since Prime Minister Robert Menzies took Australia into the war against Hitler on 3 September 1939. Children across the country were being reared by their mothers and extended families and friends.

Ted enlisted as soon as he finished his law degree. He was an impatient young man who was desperate for âsome kind of an adventure', but his parents persuaded him to qualify first.

4

By the time he signed up at the Victoria Barracks in Paddington on 25 May 1940, he was working as a judge's associate. Ted was excited about the war but he must have had mixed emotions: he was in love, infatuated even, with the young Frenchwoman he had met through mutual friends in a Sydney restaurant.

Sylvette Cargher was not part of Ted's university crowd. She was more exotic and stylish than the young women he mixed with in the city. She was small, with dark hair and eyes, distinctive rather than beautiful, unlike the robust, fair-haired, sunburnt girls Ted had known in the bush where he had grown up. He was drawn to the young European woman who seemed so worldly with her deep voice and accented English, even though she lacked the formal education of his circle.

The St Johns were from a proud ecclesiastical family with a lineage detailed in those bibles of class stratification,

Debrett's Peerage & Baronetage

and

Burke's Peerage.

Ted's grandfather Henry arrived in Australia from England in 1869 ârather conscious of his family tradition, to make his fortune in NSW'.

5

He did not make his fortune but he left his mark. His eldest son, Frederick de Porte St John, Ted's father, was born in 1879 and grew into an excellent horseman who seemed destined to be a farmer. But a wealthy clergyman cousin in England sent money to Australia and Frederick, along with his younger brother Henry, was enrolled at St John's Theological College in Armidale.

6

The brothers spent their lives as Church of England pastors, with Frederick ministering to bush towns throughout the Liverpool Plains and New England.

Frederick was an imposing and handsome man and he cut a fine figure as he galloped on horseback to tend to his scattered congregation. He married Hannah Phoebe Mabel Pyrke in 1908, and the couple lived first at Boggabri, where Ted, their fifth child, was born, on 15 August 1916. The family moved soon after to Uralla and stayed there for sixteen years before moving to Quirindi in 1932 when Ted was a teenager.

Life was tough. In the 1930s depression, the family often sat down to an evening meal of bread and one boiled egg. Frederick always got the egg and his children took it in turns to get the very top of the egg as he sliced it open.

7

Despite his genial public face, Frederick often beat his children, especially the boys. While Hannah was usually the one who ordered the strapping, she always regretted the way her children were âthrashed so savagely'. Her life with Frederick was not always easy, and by the time Ted was a young man his parents' relationship had deteriorated.

8