Madeleine (12 page)

Authors: Kate McCann

Back in the apartment the cold, black night enveloped us all for what seemed like an eternity. Dianne and I sat there just staring at each other, still as statues. ‘It’s so dark,’ she said again and again. ‘I want the light to come.’ I felt exactly the same way. Gerry was stretched out on a camp bed with Amelie asleep on his chest. He kept saying, ‘Kate, we need to rest.’ He managed to drift off but only briefly, certainly for less than an hour. I didn’t even try. I couldn’t have allowed myself to entertain sleep. I felt Madeleine’s terror, and I had to keep vigil with her. I needed to be doing

something

, but I didn’t know where to put myself. I wandered restlessly in and out of the room and on to the balcony.

At long last, dawn broke.

6

FRIDAY 4 MAY

Friday 4 May. Our first day without Madeleine. As soon as it was light Gerry and I resumed our search. We went up and down roads we’d never seen before, having barely left the Ocean Club complex all week. We jumped over walls and raked through undergrowth. We looked in ditches and holes. All was quiet apart from the sound of barking dogs, which added to the eeriness of the atmosphere. I remember opening a big dumpster-type bin and saying to myself, please God, don’t let her be in here. The most striking and horrific thing about all this was that we were completely alone. Nobody else, it seemed, was out looking for Madeleine. Just us, her parents.

We must have been out for at least an hour before returning to David and Fiona’s apartment, where Sean and Amelie were now up and about. The twins, distracted by having Lily and Scarlett to play with, didn’t mention Madeleine, mercifully. Russell, Jane, Matt, Rachael and their children began to arrive. People kept telling me to have some breakfast but I couldn’t eat. I had no appetite and my throat was constricted with anxiety. In any case, how could I think about eating now? There wasn’t time to eat. Someone had Madeleine and we had to find her.

That morning I learned of the man Jane had seen in the street. Although Gerry and our friends had been trying to protect me from further distress by not telling me about this sooner, when they did I was strangely relieved. Madeleine hadn’t just disappeared off the face of the earth. There was

something

to work on.

This man was around thirty-five, forty years old, dark-haired and of southern European or Mediterranean appearance. His everyday clothes – beige or gold-coloured trousers and a dark jacket – gave Jane the impression he was not a tourist. He was carrying the sleeping child horizontally across his arms, the child’s legs dangling. Though she had no reason, at that point, to be at all suspicious of him, clearly there was something odd enough about what she saw for her to register the image. While he had been dressed for the cold evening, the child was barefoot and not covered by a blanket. Although Jane had never seen or known about Madeleine’s Eeyore pyjamas, her description of this child’s night clothes – light-coloured pink or white pyjamas with a ‘trailing’ or floral pattern and turn-ups on the bottoms – matched Madeleine’s almost exactly. From the style of these pyjamas, she had also assumed the child was a girl.

There was little doubt in my mind then, nor is there now, that what Jane saw was Madeleine’s abductor taking her away. But in spite of the fact that she’d reported this to both the GNR and PJ straight away, it would be 25 May before her description of the man and child was released to the press.

I have never felt any anger or disappointment whatsoever towards Jane. On the contrary, I was grateful someone had seen something. I’m sure this experience has been a terrible burden for her to carry around with her every day since and I do feel for her. There have been many occasions when I have visualized myself walking up that road instead of Jane. Would I even have noticed the man and child? Seen that it was my daughter? Would it have dawned on me, out of the blue, what was happening? If not, after going into the apartment and finding Madeleine missing, would I instantly have made the connection and been able to chase after him? I’ve even pictured myself catching up with him and grabbing him by the shoulder. Saving Madeleine.

Around 8am, I started to receive text messages and calls from friends back in the UK who were seeing and hearing news bulletins – messages like: ‘Please tell me it’s not

your

Madeleine.’

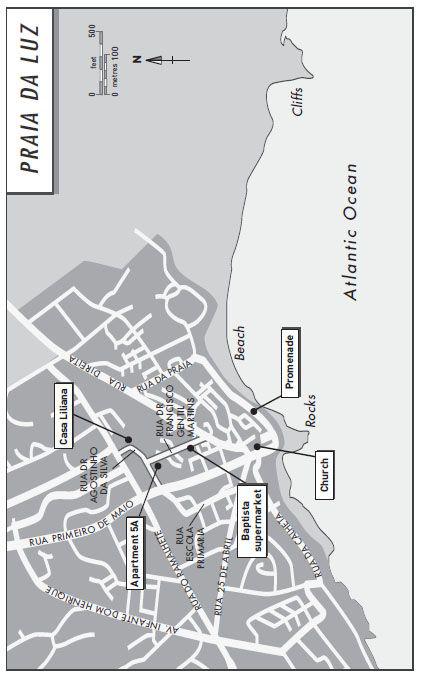

At about nine o’clock we all went out on to Rua Dr Agostinho da Silva to find out what was going on and to look out for the PJ. The GNR patrol was still in evidence, although again, there didn’t seem to be much sense of urgency. So what had the police been doing? It was hard to tell. According to the PJ files, to which we did not have access until August 2008, two patrol dogs were brought to Praia da Luz at 2am on 4 May and four search-and-rescue dogs at 8am. I don’t remember seeing any police dogs until the morning, and if there were any specific police searches overnight, they were not apparent. The only searches I was aware of were those carried out by ourselves, fellow guests and the Mark Warner staff.

According to the files, the tracker dogs did not go out until 11pm on 4 May. At some point in the first twenty-four hours (I could not say when exactly, but probably that morning) I recall one of the GNR patrol officers asking us for some of Madeleine’s clothing or belongings to enable these dogs to identify her scent. I fetched the pink princess blanket she took to bed with her every night, which they took, and some of her clothes, which they didn’t.

Several people I recognized as other Mark Warner guests were milling around and a few of the men offered to help. Steve Carpenter told us that he had approached John Hill, the resort manager, insisting that all the apartments, occupied or not (and as it was the low season, many were empty), should be opened up and searched. There had been no house-to-house inquiries at all and there wouldn’t be for some hours to come. To this day, I don’t know that this task has been completed.

A lady from an apartment across Rua Dr Gentil Martins, overlooking our little side gate, came over to speak to us. She said that the previous night she had seen a car going up the Rocha Negra – the black, volcanic cliff that dominates the village. There was a track leading to the Rocha Negra but nobody remembered ever having noticed any vehicle that far up in the daytime, let alone at night. This immediately conjured visions of Madeleine being disposed of somewhere on the overhanging cliff. I went to tell one of the police officers who was able to speak a little English. He was quite dismissive. It would have been one of the GNR men checking the area, he said.

The texts and phone calls kept coming. By this time our friend Jon Corner, a creative director in media production in Liverpool, was circulating photographs and video footage of Madeleine to the police, Interpol and broadcasting and newspaper news desks. This was in accordance with the standard advice of the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children in the US, which advocates getting an image of a missing child into the public domain as soon as possible. A colleague from the surgery in Melton Mowbray suggested enlisting the help of a private investigator and offered to look into the possibility. I was bemused. Back then, I thought of private investigators – if I thought of them at all – as lone mavericks like Jim Rockford in

The Rockford Files

. And at that stage I honestly didn’t know what we needed, though it certainly felt like more than we had. Had I known what I know now, perhaps I would have taken her advice.

A forensic team also arrived from Lisbon that Friday. Having moved out of apartment 5A, we weren’t aware of exactly when, but presumably it was some time in the morning. All we saw of them were TV images of a woman in her street clothes dusting the shutters outside the children’s room. Her shoulder-length hair was blowing free and I seem to recall that in some shots she wasn’t wearing any gloves, either.

Not having slept for some twenty-six hours I was starting to feel quite jaded but my mind was teeming with horrific images. A middle-aged British lady suddenly materialized beside me and introduced herself. She announced that she was, or had been, a social worker or child protection officer and insisted on showing me her professional papers, including, I think, her Criminal Records Bureau certificate. She asked me to sit down on a low wall, plonked herself next to me and told me she wanted me to go through everything that had happened the previous night. She was quite pushy and her manner, her very presence, were making me feel uncomfortable and adding to my distress.

David was standing nearby. Concerned, he took me aside and pointed out that we didn’t know who this woman was or what she was doing there. He reassured me that I wasn’t obliged to speak to her if I didn’t want to. And I didn’t want to. Whoever she was, and whatever her credentials were, it was an inappropriate intrusion. And something about it, something about her, just didn’t feel right. I was glad I extricated myself. This woman would pop up several times in the days and months to come and I still don’t really know who she is or what she was trying to achieve.

Steve Carpenter returned with a man who had offered his assistance. He was, he’d told Steve, bilingual in English and Portuguese and could maybe assist with interpreting. I was grateful for any help we could get. This man was in his thirties, wore glasses and there was something unusual about one of his eyes – a squint, I thought at the time (I have since been told he is blind in one eye). He seemed very personable and was happy to be of service. When one of the GNR officers came over to request more details about Madeleine and any distinguishing features she had, this man stepped in to translate.

I was holding a photograph of Madeleine, which he asked to see. As he studied it, he told me about his daughter back in England who was the same age, and who, he said, looked just like Madeleine. I was a little irked by this. In the circumstances, it seemed rather tactless, even if he was simply trying to empathize. I didn’t think his daughter could possibly be as beautiful as Madeleine – though of course, as her mum, I didn’t think any other little girl could be as beautiful as Madeleine. When he had finished translating, he turned and began to walk briskly away. Realizing I didn’t know his name, I caught up with him and asked.

‘Robert,’ he said.

‘Thank you, Robert,’ I said.

It was about 10am by the time a couple of PJ officers turned up. (One of them, in his thirties, tall and well built, I thought of for ages simply as John. I’m not sure he ever gave us his name, but later – much later – we found out that it was João Carlos.) They told us they had to take us and our friends to the police station in Portimão. We couldn’t all go at once as somebody needed to look after the children. After some discussion, it was agreed that Gerry and I, Jane, David and Matt would be interviewed first and the PJ would come back for the others later in the day. Fiona and Dianne took Sean and Amelie to their club along with the other children. While our world was falling apart, the best way of trying to keep theirs together seemed to be to stick with what they were used to.

Gerry and I travelled in one police car with the others following in a second vehicle. It was an awful journey. It took twenty, twenty-five minutes, but it felt much longer. On the way I rang a colleague – another lady of strong faith. She prayed over the phone for most of the trip, while I listened and wept at the other end. I will for ever be indebted to her for her help and support at that agonizing time.

Our first impressions of the police station were not encouraging. Basic and shabby, it didn’t seem conducive to efficiency and order. We were shown to a small waiting area separated from the control room – where calls and faxes came in – only by windows and a glass door, which was left ajar. In the control room, officers in jeans and T-shirts smoked and engaged in what sounded more like light-hearted banter than serious discussion.

I know as well as anybody that one shouldn’t judge people – or perhaps places, either – on appearances, but it all made me immensely nervous. I was appalled by the treatment we received at the police station that day. Officers walked past us as if we weren’t there. Nobody asked how we were doing, whether we were OK or needed anything to eat or drink or to use the bathroom. Our child had been stolen and I felt as if I didn’t exist. I’ve tried to rationalize it since: maybe they just couldn’t imagine how it felt to be a parent in such circumstances, or maybe they couldn’t speak English and it seemed better or easier simply to avoid us. Whatever the case, it was a horribly isolating experience.

At some point that morning we’d become aware that friends and family were appearing on television expressing our concern about the lack of police activity overnight. I think I’d registered Trisha and a good friend in Glasgow popping up on the TV in the apartment. Gerry has a memory of seeing some familiar faces on the set in the police control room. We were quite surprised that people were giving interviews but it was understandable. After all, we’d been on the phone half the night to our friends and relatives, sobbing that nothing was being done and begging for their help. And we appreciated the swift response. We were just worried that any criticism of the police might not do us or, more to the point, Madeleine, any favours.