Making Ideas Happen (12 page)

Read Making Ideas Happen Online

Authors: Scott Belsky

There is a delicate argument to be made about the benefits and costs of last-minute change. How do you differentiate between emotional doubts that surface and actual flaws? And how do you weigh the benefits of getting an early version of a product out on time (despite some flaws) against the costs of a later, more feature-rich release?

While you want to leverage the high level of focus and insight you wil garner in the final stages, you also want to test the market and be sure to compartmentalize the self-doubts that natural y arise before a project is released to the world. Some teams wil actual y use the increased level of engagement prior to shipping to lay the groundwork for the next generation of the product. In such cases, the team is informed up front that al changes proposed at this stage—except those that take less than a certain amount of time to make, say one day—wil be included in the next version. By doing this, you are able to make headway on a new-and-improved version

and

incorporate low-hanging-fruit changes—simple things that make a big difference—to the current project without compromising the launch.

Progress Begets Progress

As you successful y reach milestones in your projects, you should celebrate and surround yourself with these achievements. As a human being, you are motivated by progress. When you see concrete evidence of progress, you are more inclined to take further action.

To use progress as a motivational force, you must find a way to measure it. For an ongoing project that has already been made public, progress is embodied in the feedback and testimonials from the audience. For projects that are stil under wraps, progress reveals itself as lists of completed Action Steps or old drafts that have been marked up and since updated.

Your instinct might be to throw these relics away. After al , the work is completed. But some exceptional y productive creatives savor these items as testaments to progress.

They surround themselves with artifacts of completed work.

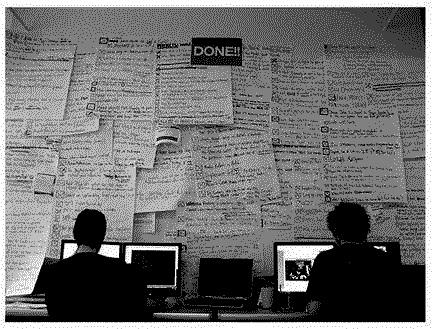

The inspiration to generate ideas comes easy, but the inspiration to take action is more rare. Especial y amidst heavy, burdensome projects with hundreds of Action Steps and milestones, it is emotional y invigorating to surround yourself with progress. Why throw away the evidence of your achievements when you can create an inspiring monument to getting stuff done? Some teams, including the Behance team, have created “Done Wal s” covered with old Action Steps. We literal y gather up the records of completed tasks from projects—often notebook pages of checked-off actions and index cards with descriptions of features we’ve added—and then we decorate certain wal s with these artifacts. For us, the “Done Wal ” is a piece of art that reminds us of the progress we have made thus far. When we feel mired in the thick of it al , we can look up and see the wake of progress that trails behind us.

One of the past “Done Walls” in the Behance office, a motivational testament to

progress

We al need to see incremental progress in order to feel confident in our creative journeys. Proof of this concept can be found in the analogy of waiting in line. If you find yourself in a long line of people waiting to get into a concert, you wil notice that everyone keeps inching forward every few minutes as the line makes its slow advance. But if the person immediately in front of you fails to move with the rest of the line, you wil get frustrated. Even if you know that the person ahead of you wil move to catch up with the line later on, you stil get frustrated as you see the gap of space ahead growing.

Standing stil and feeling no progress is difficult. You want to keep moving with the line in order to feel productive. The incremental movements with the line don’t get you there any faster, but they feel great and keep you wil ing to wait. It is the same sensation as the one you get pushing the “Door Close” button in an elevator: even though doing so may, in fact, do nothing (many of these buttons are disabled), it is satisfying to feel you are making progress.

Feeling progress is an important part of execution. If your natural tendency is to generate ideas rather than take action on existing ideas, then surrounding yourself with progress can help you focus. When you make incremental progress, celebrate it and feature it. Surround yourself with it.

Visual Organization and Advertising Action

to Yourself

It is no secret that design is a critical element of productivity. Design helps maintain a sense of order amidst creative chaos. It is a valuable tool for managing (and control ing) our own attention spans. Design can also help us advertise actions-to-be-taken to ourselves.

On a frigid day in February 2009, I visited John Maeda, the newly minted president of the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD), to find out how the leader of one of America’s premier design schools organizes his efforts. Sworn in just months before in September 2008, Maeda was already making waves in the academic world, both for his nontraditional background and his bold management strategies.

For starters, Maeda implemented a plan for radical transparency—a topic we’l discuss later under the Forces of Community—between the RISD administration and its student body. The administration rol ed out a series of blogs, including our.risd.edu, a forum for discussion about the RISD community that Maeda contributes to regularly and on which any staff member or student can post as wel . Next, Maeda spearheaded the rol out of a network of “digital bul etin boards” strategical y placed throughout the RISD

campus. These fifty-two-inch Samsung LCDs present the community with information about events as wel as artwork, photos, and messages posted by anyone on campus.

I was eager to meet with Maeda not only to learn more about his impact at RISD, but also to hear about how his unique background had influenced his capacity to make ideas happen. Maeda is a digital artist, graphic designer, computer scientist, and educator who holds bachelor’s and master’s degrees in computer science and electrical engineering, a PhD in design science, and an MBA. Prior to joining RISD, Maeda taught media arts and sciences at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology for twelve years and served as associate director of research at the MIT Media Lab. In many ways, Maeda embodies the new twenty-first-century hybrid creative thinker/leader.

Maeda’s RISD office is a visual map of what’s on his mind. The wal s are covered with Post-its, sketches, plans, and programs of recent and upcoming events around the school. The space is quite different from any other university president’s office you’re likely to see, and Maeda admits it. “If you walk into my office,” he explained, “you’l be shocked by it, but this is how I think. . . . I don’t think it’s the proper way for a president to decorate his office, but they aren’t decorations. It’s like spitting thoughts . . . I want to see what’s in my head.” Maeda believes that to truly organize things in his life, he needs to properly understand them. And to properly understand something—anything—he feels the need to see it and work with it visual y.

As we spoke, it became clear that Maeda believes the creative’s ability to stay organized is not natural. Instead, it must be enforced using methods like visual stimulation and wal s covered with thoughts, plans, and objectives.

Over the course of our discussion, Maeda jotted down many of my questions and comments on little rectangular Post-it notes that he careful y arranged on the table in front of him. Even as we chatted, Maeda was organizing his thoughts and comments through a visual documentation of the conversation itself—a process that mimicked his visual organizational approach to al of the projects across his life. “You can only organize something if you understand how it works,” Maeda explained.

John Maeda’s office at the Rhode Island School of Design, photographed by

Colin Williams

The teams at IDEO, the legendary design consultancy mentioned earlier, have also made visual organization a key principle across their creative process. As you enter one of IDEO’s buildings, you are struck by the free-flowing array of desks and computers —al personal workstations—in the center of the building. Employee bikes hang from the rafters, and glass-enclosed “project rooms” line the perimeter of the entire warehouse building. Each project room is a dedicated work space for a team of designers that has been assembled around a particular project.

While most visitors to the IDEO campus are struck by the creative nature of the space, I was intrigued by the physical dominance of actionable items and sketches on the wal s in each project room. One team member, Jocelyn Wyatt, noticed my intrigue and explained, “We thrive off of being surrounded by what needs to get done.”

Wyatt provided further insight into the nature of the project rooms. Staff members wil write initials on Post-it notes for things that need to be done by certain people. Field observations and nuances that must be kept in mind during product development are hung up on the wal s or on large poster boards scattered around the room. As I walked past these rooms, I imagined the utility of walking into a physical, three-dimensional to-do list and mood-board every day. When it comes to accountability and prioritization (and not letting anything slip through the cracks), nothing can beat this setup. Of course, when you’re out of the office, you’re out of the loop. Nevertheless, there is something to be learned from IDEO’s very spatial approach to project management and taking action.

You live in a world of choices. At any moment in time, you must decide what to focus on and how to use your time. While prioritization helps you focus, your mind may stil have the tendency to wander. When it comes to productivity, this tendency often works against you. Maeda, the teams at IDEO, and many others use visual design to organize and understand information—and to stimulate action. As with the old adage “out of sight, out of mind,” so we learn that right before our eyes, actions thrive.

When it comes to staying focused, you must be your own personal Madison Avenue advertising agency. The same techniques that draw your attention to bil boards on the highway or commercials on television can help you become more (or less) engaged by a project. When you have a project that is tracked with a beautiful chart or an elegant sketchbook, you are more likely to focus on it. Use your work space to induce attention where you need it most. You ultimately want to make yourself feel compel ed to take action on the tasks pending, just as a marketer makes you feel compel ed to buy something.

MENTAL LOYALTY:

Maintaining Attention and Resolve

IT SHOULD BE

clear by now that organizing life into a series of projects, managing those projects with a bias toward action, and always moving the bal forward are critical for execution.

But sticking to a schedule and maintaining loyalty to ideas is hard. Execution is rarely comfortable or convenient. You must accept the hardships ahead and anticipate the spotlights of seduction that are liable to stifle your progress.

You can only stay loyal to your creative pursuits through the awareness and control of your impulses. Along the journey to making ideas happen, you must reduce the amount of energy you spend on stuff related to your insecurities. You must also learn to withstand external pressures that can deter you from your path.

Rituals for Perspiration

Despite the many best practices of organizations with a bias toward action, execution ultimately boils down to sheer perspiration.

Roy Spence, chairman of GSD&M Idea City—the powerful ad agency behind brands such as Southwest Airlines, Wal-Mart, Krispy Kreme, and the famous “Don’t Mess with Texas” campaign—was once asked by

Fast Company

magazine how he keeps up the pace amidst serious competitors vying for his firm’s accounts. “The one thing that wil out-trump everything is just to out-work the bastards,” he proclaimed. “You’ve got to out-work them, out-think them, and out-passion them. But what a thril .”

Perspiration is the best form of differentiation, especial y in the creative world. Work ethic alone can single-handedly give your ideas the boost that makes al the difference.