Man Who MIstook His Wife for a Hat (16 page)

Read Man Who MIstook His Wife for a Hat Online

Authors: Oliver Sacks

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Social Scientists & Psychologists, #Literary Criticism, #General, #Medical, #Neurology, #Psychology, #Clinical Psychology, #Mental Illness, #Neuropsychology, #Psychopathology, #Physiological Psychology, #sci_psychology

BOOK: Man Who MIstook His Wife for a Hat

13.48Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

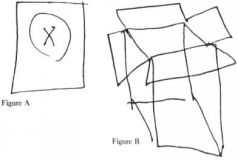

A few days later I saw him again, very energised, very active, thoughts and feelings flying everywhere, high as a kite. I asked him again to draw the same figure. And now, impulsively, without pausing for a moment, he transformed the original to a sort of trapezoid, a lozenge, and then attached to this a string-and a boy (Figure C). 'Boy flying kite, kites flying!' he exclaimed excitedly.

I saw him for the third time a few days after this, and found him rather down, rather Parkinsonian (he had been given Haldol to quiet him, while awaiting final tests on the spinal fluid). Again I asked him to draw the figure, and this time he copied it dully,

Excited elaboration ('an open carton')

correctly, and a little smaller than the original (the 'micrographia' of Haldol), and with none of the elaborations, the animation, the imagination, of the others (Figure D). 'I don't "see" things any more,' he said. 'It looked so real, it looked so

alive

before. Will everything seem dead when I am treated?'

alive

before. Will everything seem dead when I am treated?'

The drawings of patients with Parkinsonism, as they are 'awakened' by L-Dopa, form an instructive analogy. Asked to draw a tree, the Parkinsonian tends to draw a small, meagre thing, stunted, impoverished, a bare winter-tree with no foliage at all. As he 'warms up', 'comes to', is animated by L-Dopa, so the tree acquires vigour, life, imagination-and foliage. If he becomes too excited, high, on L-Dopa, the tree may acquire a fantastic ornateness and exuberance, exploding with a florescence of new branches and foliage with little arabesques, curlicues, and what-not, until finally its original form is completely lost beneath this enormous, this baroque, elaboration. Such drawings are also rather characteristic of Tourette's-the original form, the original thought, lost in a jungle of embellishment-and in the so-called 'speed-art' of am-

phetaminism. First the imagination is awakened, then excited, frenzied, to endlessness and excess.

What a paradox, what a cruelty, what an irony, there is here- that inner life and imagination may lie dull and dormant unless released, awakened, by an intoxication or disease!

Precisely this paradox lay at the heart of

Awakenings;

it is responsible too for the seduction of Tourette's (see Chapters Ten and Fourteen) and, no doubt, for the peculiar uncertainty which may attach to a drug like cocaine (which is known, like L-Dopa, or Tourette's, to raise the brain's dopamine). Thus Freud's startling comment about cocaine, that the sense of well-being and euphoria it induces '. . . in no way differs from the normal euphoria of the healthy person … In other words, you are simply normal, and it is soon hard to believe that you are under the influence of any drug'.

Awakenings;

it is responsible too for the seduction of Tourette's (see Chapters Ten and Fourteen) and, no doubt, for the peculiar uncertainty which may attach to a drug like cocaine (which is known, like L-Dopa, or Tourette's, to raise the brain's dopamine). Thus Freud's startling comment about cocaine, that the sense of well-being and euphoria it induces '. . . in no way differs from the normal euphoria of the healthy person … In other words, you are simply normal, and it is soon hard to believe that you are under the influence of any drug'.

The same paradoxical valuation may attach to electrical stimulations of the brain: there are epilepsies which are exciting and addictive-and may be self-induced, repeatedly, by those who are prone to them (as rats, with implanted cerebral electrodes, compulsively stimulate the 'pleasure-centres' of their own brain); but there are other epilepsies which bring peace and genuine well-being. A wellness can be genuine even if caused by an illness. And such a paradoxical wellness may even confer a lasting benefit, as with Mrs O'C. and her strange convulsive 'reminiscence' (Chapter Fifteen).

We are in strange waters here, where all the usual considerations may be reversed-where illness may be wellness, and normality illness, where excitement may be either bondage or release, and where reality may lie in ebriety, not sobriety. It is the very realm of Cupid and Dionysus.

12

A Matter of Identity

'What'll it be today?' he says, rubbing his hands. 'Haifa pound of Virginia, a nice piece of Nova?'

(Evidently he saw me as a customer-he would often pick up the phone on the ward, and say 'Thompson's Delicatessen'.)

'Oh Mr Thompson!' I exclaim. 'And who do you think I am?'

'Good heavens, the light's bad-I took you for a customer. As if it isn't my old friend Tom Pitkins. . . Me and Tom' (he whispers in an aside to the nurse) 'was always going to the races together.'

'Mr Thompson, you are mistaken again.'

'So I am,' he rejoins, not put out for a moment. 'Why would you be wearing a white coat if you were Tom? You're Hymie, the kosher butcher next door. No bloodstains on your coat though. Business bad today? You'll look like a slaughterhouse by the end of the week!'

Feeling a bit swept away myself in this whirlpool of identities, I finger the stethoscope dangling from my neck.

'A stethoscope!' he exploded. 'And you pretending to be Hymie! You mechanics are all starting to fancy yourselves to be doctors, what with your white coats and stethoscopes-as if you need a stethoscope to listen to a car! So, you're my old friend Manners from the Mobil station up the block, come in to get your boloney-and-rye . . .'

William Thompson rubbed his hands again, in his salesman-grocer's gesture, and looked for the counter. Not finding it, he looked at me strangely again.

'Where am I?' he said, with a sudden scared look. 'I thought I

was in my shop, doctor. My mind must have wandered . . . You'll he wanting my shirt off, to sound me as usual?'

'No, not the usual. I'm

not

your usual doctor.'

not

your usual doctor.'

'Indeed you're not. I could see that straightaway! You're not my usual chest-thumping doctor. And, by God, you've a beard! You look like Sigmund Freud-have I gone bonkers, round the bend?'

'No, Mr Thompson. Not round the bend. Just a little trouble with your memory-difficulties remembering and recognising people.'

'My memory has been playing me some tricks,' he admitted. 'Sometimes I make mistakes-I take somebody for somebody else . . . What'll it be now-Nova or Virginia?'

So it would happen, with variations, every time-with improvisations, always prompt, often funny, sometimes brilliant, and ultimately tragic. Mr Thompson would identify me-misidentify, pseudo-identify me-as a dozen different people in the course of five minutes. He would whirl, fluently, from one guess, one hypothesis, one belief, to the next, without any appearance of uncertainty at any point-he never knew who I was, or what and where

he

was, an ex-grocer, with severe Korsakov's, in a neurological institution.

he

was, an ex-grocer, with severe Korsakov's, in a neurological institution.

He remembered nothing for more than a few seconds. He was continually disoriented. Abysses of amnesia continually opened beneath him, but he would bridge them, nimbly, by fluent confabulations and fictions of all kinds. For him they were not fictions, but how he suddenly saw, or interpreted, the world. Its radical flux and incoherence could not be tolerated, acknowledged, for an instant-there was, instead, this strange, delirious, quasi-coherence, as Mr Thompson, with his ceaseless, unconscious, quick-fire inventions, continually improvised a world around him-an Arabian Nights world, a phantasmagoria, a dream, of ever-changing people, figures, situations-continual, kaleidoscopic mutations and transformations. For Mr Thompson, however, it was not a tissue of ever-changing, evanescent fancies and illusion, but a wholly normal, stable and factual world. So far as

he

was concerned, there was nothing the matter.

he

was concerned, there was nothing the matter.

On one occasion, Mr Thompson went for a trip, identifying himself at the front desk as 'the Revd. William Thompson', ordering a taxi, and taking off for the day. The taxi-driver, whom we later spoke to, said he had never had so fascinating a passenger, for Mr Thompson told him one story after another, amazing personal stories full of fantastic adventures. 'He seemed to have been everywhere, done everything, met everyone. I could hardly believe so much was possible in a single life,' he said. 'It is not exactly a single life,' we answered. 'It is all very curious-a matter of identity.'*

Jimmie G., another Korsakov's patient, whom I have already described at length (Chapter Two), had long since

cooled down

from his acute Korsakov's syndrome, and seemed to have settled into a state of permanent lostness (or, perhaps, a permanent now-seeming dream or reminiscence of the past). But Mr Thompson, only just out of hospital-his Korsakov's had exploded just three weeks before, when he developed a high fever, raved, and ceased to recognise all his family-was still on the boil, was still in an almost frenzied confabulatory delirium (of the sort sometimes called 'Korsakov's psychosis', though it is not really a psychosis at all), continually creating a world and self, to replace what was continually being forgotten and lost. Such a frenzy may call forth quite brilliant powers of invention and fancy-a veritable confabulatory genius-for such a patient

must literally make himself (and his world) up every moment.

We have, each of us, a life-story, an inner narrative-whose continuity, whose sense, is our lives. It might be said that each of us constructs and lives, a 'narrative', and that this narrative

is

us, our identities.

cooled down

from his acute Korsakov's syndrome, and seemed to have settled into a state of permanent lostness (or, perhaps, a permanent now-seeming dream or reminiscence of the past). But Mr Thompson, only just out of hospital-his Korsakov's had exploded just three weeks before, when he developed a high fever, raved, and ceased to recognise all his family-was still on the boil, was still in an almost frenzied confabulatory delirium (of the sort sometimes called 'Korsakov's psychosis', though it is not really a psychosis at all), continually creating a world and self, to replace what was continually being forgotten and lost. Such a frenzy may call forth quite brilliant powers of invention and fancy-a veritable confabulatory genius-for such a patient

must literally make himself (and his world) up every moment.

We have, each of us, a life-story, an inner narrative-whose continuity, whose sense, is our lives. It might be said that each of us constructs and lives, a 'narrative', and that this narrative

is

us, our identities.

If we wish to know about a man, we ask 'what is his story-his real, inmost story?'-for each of us

is

a biography, a story. Each of us

is

a singular narrative, which is constructed, continually, unconsciously, by, through, and in us-through our perceptions,

is

a biography, a story. Each of us

is

a singular narrative, which is constructed, continually, unconsciously, by, through, and in us-through our perceptions,

*A very similar story is related by Luria in

The Neuropsychology of Memory

(1976), in which the spell-bound cabdriver only realised that his exotic passenger was ill when he gave him, for a fare, a temperature chart he was holding. Only then did he realise that this Scheherazade, this spinner of 1001 tales, was one of 'those strange patients' at the Neurological Institute.

The Neuropsychology of Memory

(1976), in which the spell-bound cabdriver only realised that his exotic passenger was ill when he gave him, for a fare, a temperature chart he was holding. Only then did he realise that this Scheherazade, this spinner of 1001 tales, was one of 'those strange patients' at the Neurological Institute.

our feelings, our thoughts, our actions; and, not least, our discourse, our spoken narrations. Biologically, physiologically, we are not so different from each other; historically, as narratives-we are each of us unique.

To be ourselves we must

have

ourselves-possess, if need be re-possess, our life-stories. We must 'recollect' ourselves, recollect the inner drama, the narrative, of ourselves. A man

needs

such a narrative, a continuous inner narrative, to maintain his identity, his self.

have

ourselves-possess, if need be re-possess, our life-stories. We must 'recollect' ourselves, recollect the inner drama, the narrative, of ourselves. A man

needs

such a narrative, a continuous inner narrative, to maintain his identity, his self.

This narrative need, perhaps, is the clue to Mr Thompson's desperate tale-telling, his verbosity. Deprived of continuity, of a quiet, continuous, inner narrative, he is driven to a sort of nar-rational frenzy-hence his ceaseless tales, his confabulations, his mythomania. Unable to maintain a genuine narrative or continuity, unable to maintain a genuine inner world, he is driven to the proliferation of pseudo-narratives, in a pseudo-continuity, pseudo-worlds peopled by pseudo-people, phantoms.

What is it

like

for Mr Thompson? Superficially, he comes over as an ebullient comic. People say, 'He's a riot.' And there

is

much that is farcical in such a situation, which might form the basis of a comic novel. * It

is

comic, but not just comic-it is terrible as well. For here is a man who, in some sense, is desperate, in a frenzy. The world keeps disappearing, losing meaning, vanishing-and he must seek meaning,

make

meaning, in a desperate way, continually inventing, throwing bridges of meaning over abysses of meaninglessness, the chaos that yawns continually beneath him.

like

for Mr Thompson? Superficially, he comes over as an ebullient comic. People say, 'He's a riot.' And there

is

much that is farcical in such a situation, which might form the basis of a comic novel. * It

is

comic, but not just comic-it is terrible as well. For here is a man who, in some sense, is desperate, in a frenzy. The world keeps disappearing, losing meaning, vanishing-and he must seek meaning,

make

meaning, in a desperate way, continually inventing, throwing bridges of meaning over abysses of meaninglessness, the chaos that yawns continually beneath him.

But does Mr Thompson himself know this, feel this? After finding him 'a riot', 'a laugh', 'loads of fun', people are disquieted,

*Indeed such a novel has been written. Shortly after 'The Lost Mariner' (Chapter Two) was published, a young writer named David Gilman sent me the manuscript of his book

Croppy Boy,

the story of an amnesiac like Mr Thompson, who enjoys the wild and unbridled license of creating identities, new selves, as he whims, and as he must-an astonishing imagination of an amnesiac genius, told with positively Joycean richness and gusto. 1 do not know whether it has been published; 1 am very sure it should be. I could not help wondering whether Mr Gilman had actually met (and studied) a 'Thompson'-as I have often wondered whether Borges' 'Funes', so uncannily similar to Luria's Mnemonist, may have been based on a personal encounter with such a mnemonist.

Croppy Boy,

the story of an amnesiac like Mr Thompson, who enjoys the wild and unbridled license of creating identities, new selves, as he whims, and as he must-an astonishing imagination of an amnesiac genius, told with positively Joycean richness and gusto. 1 do not know whether it has been published; 1 am very sure it should be. I could not help wondering whether Mr Gilman had actually met (and studied) a 'Thompson'-as I have often wondered whether Borges' 'Funes', so uncannily similar to Luria's Mnemonist, may have been based on a personal encounter with such a mnemonist.

Other books

Facade by Nyrae Dawn

Six Heirs by Pierre Grimbert

The Pledge by Howard Fast

Road of the Dead by Kevin Brooks

Indiscretion by Jillian Hunter

The Nothing Girl by Jodi Taylor

Montana Wrangler by Charlotte Carter

The Lonely Hearts Club by Radclyffe

Indecent Suggestion by Elizabeth Bevarly