Maniac Eyeball (21 page)

Its beauty is a magic of imponderables. Where else does one find so desolate a feeling, such abandoned pathways, such indigent roads, so sparse a vegetation, but also where an imagination living with more luxury in the excellence of the line of the hills, the design of the bay, the shape of the rocks, the fine and shaded gradation of the espaliers leading down to the sea. Solitude, grace, sterility, elegy – the contrasts come together as in the nature of man, and we live in a perpetual set of miracles. O excellence of those things from which my eyes will never cease to take nourishment and which I proclaim to constitute the most beautiful landscape in the world!

One day, from Peni Pass, which overlooks the perfect lines of the gulf of my dreams, just when I had been cursed by my father, I hesitated to look back a last time and engrave each detail of the blessed place in my memory. But I stood motionless, eyes set on the road before me, for I knew my back was leaning against the land of my childhood that stuck to my skin as the bark to the tree. Hence forth, on the contrary, Catalonia lived within me and inspired my hand. Nothing could separate us, not a father’s curse, nor even the revolt of a people.

Around the time when Luis Companys proclaimed the Republic of Catalonia in October 1934, I was giving a lecture at Barcelona. The savagery of mankind grabbed me by the throat at that time and I almost fell into the trap of that awful stupidity, civil war. Bombs were bursting. A general strike had the city paralyzed. The paranoia of war was in every heart. The old dealer Dalmau, who was my host, came to wake us very early in the morning, appearing to emerge from a nightmare, hair on end, beard unkempt, flushed in the face, his fly open like some wild animal who had just escaped a pack of husbands on his tail to castrate him. “We’re getting out,” he said, “it’s civil war.”

Easier said than done. Two hours to get a safe-conduct. Half a day to find a driver with car willing to take us for his weight in gold. Everywhere, wild drunken rioters.

Machine guns at windows. People made dates to meet in urinals so as to carry on their business without looking like conspirators. Fear reigned, with death panting behind its throne. I can still see the little village where we stopped for gasoline. The men are carrying ridiculous but lethal weapons, while under a big tent people are dancing to the tune of the “Beautiful Blue Danube.” Carefree as you like, girls and boys, in each other’s arms, waltz madly. Some are playing Ping-Pong, while old men wait to be served from a barrel of wine. I look out the car door at this idyllic picture of a small Catalan village celebrating, and then I hear the voices of the four men who, over pregnant silences, are exchanging remarks about Gala’s luggage, which seems provocative, offensive to them, in its ostentation. They feel inspired by an anarchist proletarian hatred. One of them looking me in the eye suggests we ought to be shot, there and then, as an example. I fall back on the car seat. I gasp for breath. My cock shrivels like a tiny earthworm before the vicious mouth of a pike. I can hear our driver’s shouted swearwords ordering them to get out of our way. They comply docilely, cowed by the tough words, the blessed paranoia of The Word!

Arriving at the French border at Cerbère, I swore to keep out of the way of revolutions. On the return trip the driver was the victim of a machine-gun burst. I can still see how he had picked up a stray Ping-Pong ball and returned it to the awkward player with great gentleness. I still shudder at the idea of the idiotic death unleashed by the wildmen on all sides.

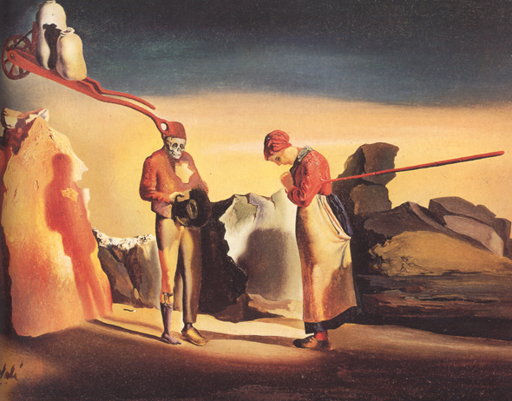

I started to paint

La Premonition de la Guerre Civile

(

Premonition Of Civil War

; also known as

Soft Construction

with Boiled Beans),

in which intermingled arms and legs choke each other, as it prophetically foretells the reciprocal killings in a Spain fascinated with the horror of self-destruction. The Spanish corpse was soon to let the world know what its guts smelled like. The severed head of an archbishop would be dragged through the streets of Barcelona. With sublime and horrible rage the children of Spain would disembowel each other with irons red hot with hatred. They would offer them selves in holocaust with admirable courage like Incas going to be sacrificed for the delight of dying. There would be killings without reason, or just for killing’s sake, for monetary gain, out of derision, arbitrariness, ideal, or love. Lorca would be killed, because he was the greatest Spaniard of them all and the most symbolic of all the dead.

He was a member of no party. In August 1936, near Granada, he was literally kidnapped. Neither his body nor his grave was found, as he once had foretold in a poem. The terror of the most hideous nightmare extended its iron grip over the whole country. I closed eyes and ears so as to know nothing about it, but the stories of the most terrifying atrocities still reached me and haunted me like nightmares.

As the crowds fornicated with suffering and death under the aegis of the Marquis de Sade, I left for Italy to retrace the footsteps of Stendhal through Rome. The Spanish sky was turning red with blood, and I told my self it was good to be alive, to feel one existed.

Having thus been able to prove out the bankruptcy of all ideas, all theses, all commitments, I became irrevocably Dalínian. Knowing that out of this offal of disemboweled bodies in the ruins of its cities Spain would one day rise again, returning to its traditional truth, its great male strength, and that I, the Catalan, would be there after this episode of revolutionary confusion to recall the existence of sacred values, I painted

Paranoia, The Great Paranoiac, Le

Cannibalisme d’Automne

(

Autumn Cannibalism

) – while the fighting was going on at the gates of Madrid – and

Le

Sommeil

(

Sleep

), which indicated the time necessary for the horror to be forgotten.

And indeed, such a time did come. Some thirty of my friends from Cadaqués had been shot. Europe was not quite cured of the “ism” illness or the basic infections of the nineteenth century, but I went back to my house in the middle of the olive trees facing the most beautiful gulf in the world.

The village steeple was damaged, but the rocks of Cape Creus still went through their eternal metamorphoses in the iridescent spume of waves shattering on their backs. And in their renewed mirages I could see, as a fortune-teller reading coffee grounds, the fantastic images of the fate of human paranoia whose most perfect Catalan fruit I am.

The point is not for Spain to become European, but rather that all of my country take inspiration from the Catalan soul; that Catalonia “Geronimize” itself; that Gerona start to reflect “Figueras-ism”; as Cadaqués becomes one cell within Figueras. Then all of Europe will be Spanish. I believe only in ultra-localism.

“TO ME, SPIRITUALITY IS VISCERAL.”

[1] This jewel was acquired by the Cheatham Collection.

[2] See Chapter 3.

Chapter Ten: How To Become Paranoiac-Critical

I am living, controlled delirium. I am because I am in delirium, and am in delirium because I am. Paranoia is my very person, though both dominated and exalted by my consciousness of being. My genius resides in that double reality of my personality; the mar riage at the highest level of critical intelligence and its irrational and dynamic opposite. I overthrow all boundaries and continually establish new structures for thinking.

Long before 1933 when I read Jacques Lacan’s admirable thesis,

De la Psychose Paranoïaque dans ses

Rapports avec la Personnalité

(

Of Paranoiac Psychosis In

Its Relationships To Personality

), I was perfectly aware of what force was mine. Gala had exorcised me, but the deeper intuition of the quality of my genius had always been present in my mind and principally in my work.

Lacan threw a scientific light on a phenomenon that is obscure to most of our contemporaries – the expression: paranoia – and gave it its true significance. Psychiatry, before Lacan, committed a vulgar error on this account by claiming that the systematization of paranoiac delirium developed “after the fact” and that this phenomenon was to be considered as a case of “reasoning madness”. Lacan showed the contrary to be true: the delirium itself is a systematization.

It is born systematic, an active element determined to orient reality around its line of force. It is the contrary of a dream or an automatism which remains passive in relation to the movingness of life. Paranoiac delirium asserts itself and conquers. Surrealist actions bring dream and automatism into the concrete; but paranoiac delirium is the very essence of Surrealism and needs only its own force.

All I had to do was organize the conquest of the irrational in function of my gifts of genius. I always go straight to the heart of the problem in all my thoughts and all my actions. Everything that terrifies others delights me, the fears and phantasms that others commonly carefully repress are to me so many fresh sources for my critical intelligence, but one would have to be far more foolish than I to try to analyze the complexity of my intentions and motivations. I who live them am far from understanding all about them!

Fortunately, there are still my works which, subjected to the most objective examination, may allow some of the truths I have been dredging up from the depths to come through.

How Dalí Defines His Art From This Viewpoint

All my art consists in concretizing with the most implacable precision the irrational images I tear out of my paranoia. I have per fected the most systematic and evolutionary of Surrealist methods for the conquest of the irrational. When you consider the results obtained by the recital of dreams, automatic writing, or objects with symbolic functionings, you become aware of how easily one can reduce the rich catches of the dream world and the wonderful to commonplaces and obvious logic; even if one, certainly essential, part remains an impenetrable nucleus, it is evident that the sentiment you feel about the in trinsic value of such testimonies diminishes their bearing to the extent that we are incapable of proving them out. Poetic escape is no criterion and the fantastic remains but a literary image if it is not actually experienced. The Surrealist artist-poet must materialize in the concrete the forms of the delirium which is the secret road leading to the unknown world of paranoia.

I conceived the experimental formula of paranoiac-criticism around 1929. According to current usage, the term paranoia denotes the phenomenon of delirium manifested in a series of systematic interpretive associations. My method consists of spontaneously explaining the irrational knowledge born of delirious associations by giving a critical interpretation of the phenomenon. Critical lucidity plays the part of a photographic developer, and in no way influences the course of the paranoiac force. The will to systematization being linked to paranoiac expression of which it is an integral part, what needs be done is only objectively to shed light on the instantaneous fact that arises from the paranoiac act and the clash of systematization with the real. Critical lucidity records evolution and production. On a Surrealist level, paranoiac-critical activity takes the shape of the creation of the objective chance that re-creates the world and delirium actually becomes reality.

Anamorphic hysteria is one example of this. I have told how, looking for an address in a stack of old papers, I found a snapshot that I thought was a reproduction of a Picasso painting. I could perfectly make out the two eyes, the spread-out nose with the two holes for nostrils, and two mouths.

That very morning I had been giving extended thought to the deformation of faces in Picasso’s Cubist pictures, in his African period. And then, as I looked more closely at the second mouth in the face, suddenly it all disappeared and I realized I was the victim of an illusion. I had been looking at the photograph vertically, whereas it was supposed to be taken horizontally. The subject was three groups of Negroes lying or sitting before a round hut.

I was later to show this “face” to André Breton, who had no trouble in immediately recognizing it as the head of the Marquis de Sade. He could see the powdered periwig. At that time, Breton was mainly concerned with the divine marquis. We had found it amusing to point out the similarity of a detail in my

L’Enigme du Désir

(

The Enigma Of Desire

), a 1929 painting, with a photo of a weirdly shaped rock at Cape Creus. We might as well have pointed to some of the shapes of Gaudí’s Sagrada Familia. The truth of it is that my paranoiac force projected a series of systematic images that I consciously apprehended and tried to concretize. I am neither copyist nor image maker, but am delirious.

I once said we Surrealists and our works were “caviar”, the dialectically (Dalíectically) highest quality of caviar, in a word, the greatest condensation of the mystery of the poetry of truth, truly sublime food, a bridge to the great unknown in a world turned gamy with awful technology and materialism. Our doings were in between science and art on the river of the irrational of which we are the privileged navigators.