Maniac Eyeball (33 page)

“I don’t know what I’m trying to forget,” she would say; “maybe that I’m alive. And I keep moving to pretend that I’m trying to catch up with time.”

She was very proud of her neck, “the longest neck in the world,” as she called it, and to keep it in shape, she kept her head high when she ate. She massaged it constantly, as if it were an enormous penis that she was masturbating.

She walked in her sleep, “all night in the middle of gardens”. One morning, at the Ritz, the chambermaid found a tailored suit cut out of a terrycloth robe during the night with a pair of scissors. “In the lapel, the suit had a gardenia fashioned from a hand towel.”

She told a funny story about her first evening at Maxim’s: an Englishman and his lady had just sat down, when a woman broke in, grabbed a glass and smashed it, and with the jagged stem cut up the gent’s face. “I ran away,” she said. “I climbed up the stairs and hid under a table covered by a tablecloth that came all the way down to the floor. I am terrified of blood.

“The second time, at Maxim’s, we had hardly sat down when a man came in waving a revolver and forced us all to get up and stand with our hands up. You can understand why it took me thirty years before I ever went back to that restaurant.”

Coco Chanel considered herself an artist and spoke of her self in the third person: “She took the English masculine and made it feminine. All her life, all she did was change men’s clothing into women’s: jackets, hair, neckties, wrists. Coco Chanel always dressed like the strong independent male she had dreamed of being. She set women free because she had suffered too long from not being free herself. Showing what so-called meaningless fashions can sometimes be due to!”

Was Coco Chanel Capable Of Friendship?

I think Coco Chanel gave her friendship not to beings but to entities. I was

genius

as Diaghilev was

dance

and Coco was

fashion.

She liked herself very much and talked about herself tirelessly.

Misia Sert had introduced her to Diaghilev. He treated her as a sister, though he was in love with her. When he was broke in London, after

Sleeping Beauty,

which was a resounding flop, he took refuge in Paris, at Misia’s at the Ritz. Coco was there. The next day, without telling a soul, she gave him a big check that allowed him to get started again, on the sole condition that Diaghilev was to keep her generosity a secret. This silence completely upset Diaghilev, who always expected his angels to be in love with one of the ballet members, male or female.

She backed Stravinsky’s

Rite of Spring

and

Noces,

and Diaghilev tried to pay court to her, but she sent him back to his

pas de deux

. She was doing it out of something quite other than love, perhaps to prove something to herself – her freedom, her power, her masculinity. The money she had acquired let her prove her reality in her own eyes. While at sea on the

Flying Cloud,

the yacht belonging to the Duke of Westminster, one of the great loves of her life, she heard that Diaghilev, diabetic, was on his deathbed in Venice; she forced the yacht to set sail for Venice. She got there after he died, just in time to see Diaghilev to the cemetery. Serge Lifar and Boris Kochno wanted to follow the cortège on their knees.

Coco told them to follow her, and led the procession of mourning friends followed by her two pages. But she was not one for gratitude, and paid no tribute to memory.

“Every morning, the bag of the past ought to be emptied,” she used to say, “else the weight of life drags you down and soon you’re in the dust, with the ghosts and the idiots.”

She loved Pierre Reverdy very much, to the point of hating Jean Cocteau, because he was so successful a poet.

“Thank God, the future will change all that,” she would say, “and only Reverdy and Blaise Cendrars will remain.” In Reverdy, she loved his saintliness – but he preferred the peace of Solesmes Abbey to a great love. Coco was also long fascinated by the fact that the Duke of Westminster did not mail his love letters to her, but sent the daily missive with a messenger specially dispatched from London. They did not marry because the House of Chanel could not enter into alliance with the House of England. But there was true luxury in their relationship.

Once, to apologize for having made her jealous, the Duke, during one of their yacht cruises, gave Coco an emerald; she leaned against the railing, admired the light playing on the gem, and then, having seen it, let it drop into the sea. She was being Cleopatra who, to stand up to Caesar, took the pearls the Imperator gave her and dropped them into vinegar to dissolve them.

I was often her guest at La Pausa, her villa on the Riviera. The whole

Almanach de Gotha

went bathing there, without formality. Around the Duke were Cocteau, Georges Auric, Prince Kutuzov, the Beaumonts, Serge Lifar. Back at the house, there were two huge buffets on the terrace, with cassoulet, risotto, stew, fishes in aspic. Hot and cold in profusion for all tastes. After that, we would go inside. Over her gilt iron bed, Coco had hung some useless fertility amulets.

Winston Churchill forced the Duke to marry the daughter of the royal palace’s chief of protocol. In one night, a memorable rupture scene sent all the appearances of happiness flying in smithereens. The sun disappeared; it was the ice age.

The last time I had seen Coco Chanel was at Arcachon just before the great exodus to the U.S. when the war was on. She spoke of the vacations of her girlhood at an oyster breeder’s; he took her out on his boat in the morning and gave her fresh-gathered oysters to eat. “I would spit them out disgustedly,” she said. “Later, I was sorry I had not learned to like them. When I lived at the Ritz with my fine officer, I used to have them sent up to my room and, trying to get myself to like them, invited the chambermaid to share them with me, but she unfortunately had no taste for them either. How about you, Dalí, do you like oysters?” I like tearing the oyster out of its shell as I like crushing bones so as to suck out the marrow. Whatever is sticky, gelatinous, viscous, vitreous, to me, is suggestive of gastronomical lust.

As Gala and I were about to sail again for Europe, I thought back on that conversation and my mouth watered with pleasure at the vision of the friends and the meals that lay ahead. From the boat deck, I looked at New York with satisfaction. Helena there, Coco in Paris. One of the queens of world snobbery in each capital, to say good-bye and to welcome me, and Gala in my heart and my bed. What luxury!

But what happiness to get back to the transcendent beauty of Port Lligat, my kingdom, my Platonic cave. As soon as I get back, I dip again into the splendor of the Gulf, become intoxicated with the sacred landscape that encloses the horizon. I walk on air. I forget the haughtiness of the skyscrapers and the agitation, the noise, the excitement of America. There is no way out, at the point of hypersnobbery I have reached, but to be come a mystic.

I allow the sun to seep into me and I experience the Mediterranean light. Like a burning arrow, I receive the certainty of my communication with God whose elite creature I am. My return from America is consecrated by this solemn event: after success, money, the greatest hit of snobbery, God brings me His witness. I feel I am the divinely chosen.

That is the time the government decides to declare Port Lligat “picturesque, of national interest”, thereby turning this corner of the world into a Dalínian church. I feel assured of the triumph that awaits me in Paris.

““I AM VERY FAITHFUL TO MY FRIENDS, BUT ALWAYS REASONABLY. I DO NOT EXPERIMENT WITH MY EMOTIONS WHERE THEY ARE CONCERNED. CREVEL HAD A BREAKDOWN IN A LITTLE VILLAGE WE LIVED IN AND WAS AT DEATH’S DOOR AND I COULD NOT EVEN TOUCH HIM. I ACTED AS I SHOULD HAVE, IN A WAY THAT EVERYONE CONSIDERED THE MOST DEVOTED POSSIBLE, BUT I COULD NOT BRING MYSELF TO TOUCH HIM IN ORDER TO HELP HIM. ANYTHING THAT IS SENTIMENT IS STRICTLY CHANNELED TO MY WIFE AND ALL OTHER BEINGS LEAVE ME ABSOLUTELY INDIFFERENT BUT I ACT TOWARD THEM WITH INTELLIGENCE AND REASONING.”

[1] Misia, “who harvested geniuses who were all in love with her, collected hearts and pink Ming trees: launching her fads that became fashions... imitated by the empty-headed women of high society, Misia was the queen of modern baroque. Misia sulking, pretending, a genius of perfidy, refined in her cruelty... unfulfilled, Misia whose piercing eyes were still full of laughter when her mouth was already turning into a pout.”

Chapter Fifteen: How To Pray To God Without Believing In Him

The atomic explosion of August 6, 1945, shook me seismically. Thenceforth, the atom was my favorite food for thought. Many of the landscapes painted in this period express the great fear inspired in me by the announcement of that explosion. I applied my paranoiac-critical method to exploring the world. I want to see and understand the forces and hidden laws of things, obviously so as to master them.

To penetrate to the heart of things, I know by intuitive genius that I have an exceptional means: mysticism, that is to say, deeper intuition of what is, immediate communication with the all, absolute vision by grace of truth, by grace of God.

Stronger than cyclotrons and cybernetic computers, in a moment I get through to the secrets of the real, but only facing the landscape of Port Lligat will this conviction become certainty and my entire being catch fire with the transcendental light of that high place.

On the shore at Port Lligat I understood that the Catalan sun which had already engendered two geniuses, Raymond de Se bonde, author of

Natural Theology,

and Antonio Gaudí, the creator of Mediterranean Gothic, had just caused the atom of the absolute to explode within me. I became a mystic as I watched the swallows pass by outside the window. I understood that I was to be the savior of modern painting. It all became clear and evident: form is a re action of matter under inquisitorial coercion on all sides by hard space. Freedom is what is shapeless. Beauty is the final spasm of a rigorous inquisitorial process. Every rose grows in a prison.

I had a sudden vision of the highest architecture of the human soul: Bramante’s Roman

tempietto

of San Pietro in Montorio and the Spanish Escorial, both conceived in ecstasy. “Give me ecstasy!” I shouted. “The ecstasy of God and man. Give me perfection, beauty, so I may look it in the eyes. Death to the academic, to the bureaucratic formulas of art, to decorative plagiarism, to the feeble aberrations of African art. Help me, Saint Teresa of Avila!” And I plunged into the most rigorous, architectonic, Pythago rean, and exhausting mystical reverie that can be. I became a saint. I might have become an ascetic, but I was a painter. I made myself a dermo-skeleton of a body, shoving my bones to the exterior like a crustacean, so that my soul could grow only upward toward heaven; working at it from awakening till slumber, putting to contribution the slightest digestive incidents, the least phosphenes, I succeeded in exploring myself, dissecting myself, reducing myself to an ultra-gelatinous corpuscular wave so as the better to reassemble myself in ecstasy and joy.

It was in this state of intense prophecy that I understood that the means of pictorial expression had been invented once and for all with maximum perfection and efficiency during the Renaissance, and that the decadence of modern painting came from the skepticism and lack of faith resulting from mechanistic materialism. I, Dalí, by restoring currency to Spanish mysticism, will prove the unity of the universe through my work by showing the spirituality of all substance.

I feel, sensorially and metaphysically, that the ether is non- existent. I understand the relative role of time, Heraclitus’ statement, “Time is a child”, appearing to me in blinding clarity with my limp watches taking on all their meaning. “No more denying,” I shouted at the height of ecstasy, “no more Surrealist malaise of existential angst. I want to paint a Christ that is a painting with more beauty and joy than have ever been painted before. I want to paint a Christ that is the absolute opposite of Grünewald’s materialistic, savagely anti-mystical one.” The way was laid out for me!

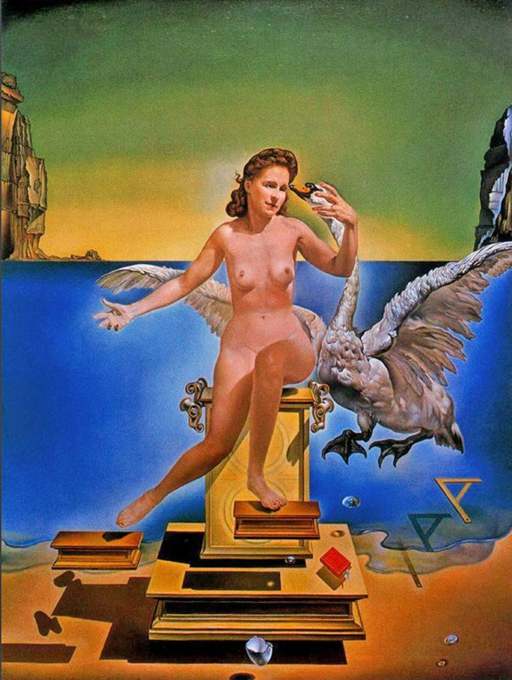

In an ebullition of ideas of genius, I decided to undertake the plastic solution of the quantum theory of energy and invented “quantified realism” so as to be master of gravity. I started to paint the

Leda Atomica,

which exalted Gala as goddess of my metaphysics, and succeeded in creating “suspended space,” and then

Dalí à l’Age de Six Ans

Quand il Croyait Etre une Jeune Fille en train de Soulever

la Peau de la Mer Pour Voir un Chien Endormi à l’Ombre

de l’Eau

(

Dalí At The Age Of Six When He Thought He Was

A Young Girl Raising The Skin Of The Sea To See a Dog

Sleeping In The Shadow Of The Water

), in which beings and things appear as foreign bodies from space. I plastically dematerialized matter, then spiritualized it in order to create energy. Each thing is a living being by virtue of the energy it contains and radiates, the density of the matter that makes it up. Each of my “subjects” is both a mineral subject to the pulsations of the world and a piece of live uranium. I succeeded through painting in giving substance to space. My

Coupole Formée par les Brouettes Contorsionnées

(

Cupola

Made Of Contorted Wheelbarrows

) is the most striking demonstration of my mystical vision. I solemnly affirm that heaven is in the center of the believer’s chest, for my mysticism is not religious alone, but nuclear and hallucinogenic; and in gold, in the painting of limp watches, or my visions of the Perpignan station, I discover the same truth. I also believe in magic and in my own destiny.