Manly Wade Wellman - Novel 1954

Read Manly Wade Wellman - Novel 1954 Online

Authors: Rebel Mail Runner (v1.1)

Rebel Mail

Runner

Manly Wade

Wellman

BY

THE SAME AUTHOR

The Last Mammoth

Wild Dogs of Drowning Creek

The Haunts of Drowning Creek

The Raiders of

Beaver

Lake

The Mystery of Lost Valley

The Sleuth Patrol

HOLIDAY

HOUSE,

NEW YORK

Text, copyright 1954 by Manly Wade Wellman

Illustrations, copyright 1954 by Stuyvesant Van Veen

PRINTED IN

U.S.A.

To

PAUL

“The

gods granted me a brother whose example stimulated me to make the most of my

powers, while his respect and affection gave me new heart

. .

—Marcus

Aurelius Antoninus

This is an imaginary story, about an

imaginary boy; but the Confederate Underground Mail Service, from Missouri to

the Deep South, was a thrilling fact of the Civil War, and its daring and

resourceful chief, Absalom Grimes, was as real as any American in history. His

memoirs exist today, and the adventures of himself and his lieutenants, some of

them retold here, are still remembered up and down the

Mississippi

River

.

Manly Wade Wellman Chapel Hill,

North

Carolina

October 15

,1953

Contents

To Save AB GRIMES

THEMISSOURI

sun was warm that April afternoon, and

Bowling Green

looked and sounded peaceful, for all the

war had been going on for two years. Barry Mills could see nothing more warlike

than the Union flag in the courthouse square, blue-coated soldiers

strolling

the plank-covered paths. Barry clucked to the

horses and turned them from

Main Street

into Court, on his way to August Batz’s

wood yard. He hunched square young shoulders under his jeans jacket, and turned

his dark head, under the shabby wool hat, to look resentfully at the load of

wood riding behind him in the wagon.

He’d

sawed and stacked and seasoned that wood out on his father’s farm. And he’d

greased the wheels and harnessed the team and loaded the wood, and when he got

to the wood yard he’d unload it again. But the pay for the wood wouldn’t go to

him—nor

to his father, either. It would go to fat,

wax-moustached Cousin Buckalew Mills, who had ridden into town ahead of Barry,

on the sturdy claybank mare that belonged to Barry’s father, too. If he was

only riding that mare himself, thought Barry, he’d just ride and ride, south

and west, till he could join his father in the Confederate Army. He was

seventeen, old enough for soldiering, and sick to death of Cousin Buck.

Barry

glowered sidelong at the row of stores on Court Street, with their wooden

porches. Might Buckalew be in one of those, hurrahing for the Yankees as he’d

hurrahed for the rebels two years ago in ’61? Buckalew was what folks called a

turncoat, first for one side, now the other. And he was a mean man to work for

on top of that; Barry could swear to the fact.

Barry

turned the team in at a gateway through a high fence of rough boards, pulled

up, and got down over the wheel in August Batz’s wood yard. The wood-dealer

lifted a broad hand in greeting. August was thick-built, but not pudgy like

Cousin Buckalew, and his big yellow-gray beard was always crinkling in a smile.

“Unload

ofer by der big pile at der side,” he directed, pointing. “Karl, you go mit,

help him take der wood from der vagon out.”

“Sure, Papa.”

Big Corporal Karl Batz of the Union infantry,

home on leave, shoved back his jaunty peaked cap and tucked up his blue sleeves

as he walked toward the wagon. “Tool ’em over here, Barry, and we’ll stack.”

“High

time you got here, boy.” That was Buckalew Mills, coming out of Mr. Batz’s

shantylike office. He wore a frock coat and a broad hat, and under his

moustache jutted a lean cheroot. “You were late, or near to it. Tardiness isn’t

a savory habit, Barry.”

“

Ach

, don’t scold der boy,” urged August

Batz good-humoredly. “He’s here, der vood’s here.

Now, vot

news gifs it in der town?”

“News?”

echoed Buckalew, and tapped ashes from his cheroot with an important air. “You

may well ask, August. The news concerns Captain Ab Grimes.” Barry, loosening

the tail gate of the wagon, started violently, but nobody noticed. Both Karl

and August turned to stare at Buckalew Mills.

“Ab

Grimes, Absalom Grimes,” repeated old August. “Der rebel mail runner, ha?”

“Absalom

Grimes, the rebel spy and traitor,” snapped Buckalew, again biting on the

cheroot.

“

Ach

,

so”

grunted August. “

So

bad as dot you call him? I hear he

brings only der letters from der secesh soldiers and from also der famblies he

takes der letters back—”

“By

the rules of warfare, he’s a spy,” interrupted Buckalew. “Anyway, they’re

offering two thousand dollars reward for him in

Saint Louis

.”

Hoisting

a log, Barry listened. Buckalew, once a clamorous secessionist, now called

Absalom Grimes a rebel spy. Buckalew had turned around so fast that the heels

of his boots were in front, you might say. Yet August Batz thought of Grimes as

only a mail carrier, though both August and his son Karl had been strong Union

men for years.

“I’ve

reckoned it plain as print,” plunged on Buckalew. “I know Ab Grimes personally,

I know his friends. You recollect Jim Glascock, who farms on the edge of

Hannibal

? Well, his daughter Lucy’s engaged to Ab

Grimes, and it so happens that Lucy Glascock’s visiting here in

Bowling Green

today.”

“Veil,”

prompted August placidly, “vot about it?” “She’s at Judge Westfall’s house,

yonder on

Church Street

, and you know the judge is a quiet hoper for the rebs to win. Well,”

and Buckalew grinned around his cheroot, “what’ll you bet that Ab Grimes isn’t

here in

Bowling

Green

,

too, visiting his sweetheart?” Stacking wood, Barry listened eagerly and

thought quickly. He, too, knew the name of Captain Absalom Grimes, the

daredevil ex-steamboater whose work and pleasure it was to slip through the

Federal lines with mail for

Missouri

’s Confederates and their families. He was

the only means of communication between anxious wives and mothers and their men

in gray, just now banished by war to

Mississippi

and

Arkansas

.

Barry

himself had received a letter last July from his soldier father, handed him by

a furtive neighbor. It had said that Jefferson Mills had survived several

fierce battles and was now a sergeant with the First Missouri Cavalry in

Shelby

’s Brigade. That letter,

Barry

knew

,

had come through Absalom Grimes, whom Buckalew

was now trying to trap for the reward.

Grimes

carried letters for Southern soldiers, he kept thinking. His father, Jeff

Mills, was a Southern soldier, and Barry would be one if he could. He had to

help Grimes. No two ways about it.

“Not

two blocks away,” Buckalew was arguing. “We can yank him right out of the

judge’s parlor.” Barry made up his mind suddenly, without quite knowing how he

would manage what he hoped to do. “Karl,” he said, “isn’t there some drinking

water around here?”

“Yonder

in the office,” Corporal Karl told him, humping his thick shoulder under a

chunk of wood. “Bring me out a dipperful, too.”

Barry

slipped around the wagon, into the little office, and slid a dipper into the

water bucket. Through the half-open door he could still hear Buckalew.

“August,

you know some folks don’t think I’m a good Union man. I’ve kind of got to prove

myself to them, capture this rebel spy—”

“

Ja

, /a,” August

agreed. “It’s duty, like vot you say. Mine boy Karl, maybe also he could find

some soldiers to help—”

“But let’s decide something right now,” interrupted Buckalew.

“I had the idea, ain’t that so? I thought of catching Grimes.

So I ought to get half the reward money, and the rest of the party

can split the other half; ain’t that fair?”

Barry

waited to.hear no more. He dropped the dipper in the bucket and wriggled out

through the rear window, open to the warm spring air. Swift and silent as a

raiding mink, Barry slid behind great stacks of wood.

“Karl,”

he heard old August calling. “Listen goot to vot Mr. Buckalew iss telling me.”

At

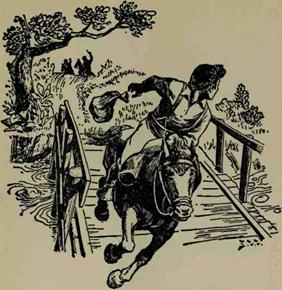

the corner of the yard, Barry knelt and prodded at the fence. A board was

loose, and gingerly he shoved it outward, then squeezed through the opening and

ran along the alley beyond. A springing rush brought him out on

Church Street

. Past two small stores he moved at a

headlong gallop, almost overturning a drowsy old man whose chair leaned back

against a door-jamb. He crossed another street beyond, vaulted a picket fence,

and sprang upon the wide pillared porch of Judge Westfall’s home.

He knocked loudly, and waited

impatiently until the door swung open. Barry looked up into a dignified dark

face above a spotless shirt front. It was the Judge’s grave Negro butler.

“I

want to talk to Miss Lucy Glascock,” said Barry breathlessly.

“Miss

Glascock?” the butler repeated. “She

know

you, young

sir?” And his wise eyes studied Barry’s shabby clothes.

“I’ve

got to see her,” pleaded Barry. “It’s—it’s a matter of life and death.”

“What’s

all that, Simon?” demanded another voice, and over the butler’s shoulder looked

the square, proud face of Judge Westfall. Dark eyes scowled under heavy white

brows. “What’s your name, son? Wait a second, I know you. Aren’t you Jeff

Mills’ boy? Let him in, Simon, and close the door.”

The

butler moved aside, and Barry stepped into the dark, spacious hall.

“Now,”

said the judge, impressively, “you spoke a lady’s name. What have you to tell

her, son?”

Barry

licked his dry lips. “Judge, I know you love the South, and you know my

father’s a Confederate cavalryman,” said Barry, all in a breath. “You can trust

me, sir. If Miss Lucy Glascock happens to be here, I want to tell her that—that

somebody she’s mighty fond of is in big danger. It’s—it’s—”

He

stammered, and fell silent. Someone else had come into the hall, Judge

Westfall’s stately wife.

“You

say I can trust you, son,” the judge reminded Barry, with great calm. “All

right, and you can trust us. So if you’re holding a name back, speak it out and

don’t be afraid.”

“Absalom

Grimes,” said Barry.

“What

about Absalom Grimes?” the judge challenged Barry. “Don’t stop talking now;

what about him?”

“They’re

coming to catch him,” said Barry, fresh words tumbling out in a torrent. “I

heard them at August Batz’s wood yard—Mr. Batz and my cousin Buckalew. They’re

bringing soldiers. They say Captain Grimes is here with Miss Glascock, and

there’s a reward for him, and—”

“Soldiers

coming!” cried the judge’s wife.

“Let

me speak to that boy,” said another voice, quietly, from a half-open door into

a side room.

Judge

Westfall glanced that way,

then

turned back to Barry.

“Mr.

Barry Mills,” he said, as though he addressed his equal in age, fortune, and

importance, “permit me to acquaint you with Captain Absalom Grimes.”

Barry

blinked at Captain Grimes with respectful interest. He had often imagined the

mail runner as gigantic and overwhelming, a headlong hero,

half

pirate, half circus acrobat, cloaked and booted and spurred, with pistol and

dagger ready to hand. Absalom Grimes was nothing like this. He was of medium

height and build, dressed neatly in dark coat and pantaloons and checkered

vest, with a fair skin, straight nose, and broad, high forehead. His dark brown

hair and beard contrasted with the light gray of his mild eyes. He might have

been a young doctor or schoolmaster. But the slim hand he held out looked

steely strong, and as he moved toward Barry his feet were silent as a cat’s on

the floor boards.