Map of a Nation (41 page)

Authors: Rachel Hewitt

T

HE THIRD VOLUME

of the

Account of the Trigonometrical Survey

described that enterprise’s progress between 1800 and 1809. But it also revealed how in that time the Ordnance Survey had not only been concerned with

creating

the First Series of maps of England and Wales. It had also become

involved in a project that, strictly speaking, was a distraction from this

central

purpose, but which contributed to contemporary questions of geodesy. By taking part in such an endeavour, Mudge returned the Ordnance Survey to its roots in the Paris–Greenwich triangulation of the 1780s and he may have hoped to demonstrate that it was still as much a scientific as a military undertaking.

Since the 1790s, Mudge had been conducting observations of the night sky to ascertain the precise latitudinal and longitudinal locations of a series of key trig points, in order to confirm the calculations made by the Trigonometrical Survey. Longitude could be found by calculating the time difference from Greenwich, for which Mudge relied on one of his uncle Thomas Mudge’s famous chronometers. In the earth’s northern

hemisphere

, latitude can be found by establishing the difference in degrees between the zenith (the highest point above the observer’s head) and the North or Pole Star, Polaris. Mudge’s celestial observations of latitude were initially designed to act as a check on the accuracy of the Trigonometrical Survey’s deductions, but towards the end of the 1790s he proposed the extension of these rather rudimentary observations into the measurement of an entire meridian arc through Britain, stretching beyond the length of one degree of latitude, which would be measured through a combination of triangulation and astronomy. This project had got under way in 1800 when Mudge recalled that, back in the early 1790s, Charles Lennox had ordered an instrument called a zenith sector from the notoriously dilatory instrument-maker Jesse Ramsden. Mudge chased up the order and Ramsden had duly ‘proceeded with little interruption’ on the instrument. In November 1800 Ramsden had died, after a long period of declining health. But Ramsden’s principal workman, John Berge, inherited his

business

and finished the sector for Mudge in such ‘a very masterly and accurate manner’ that the Superintendent suspected that the instrument ‘would not have been superior had the ingenious inventor lived to

complete

it’.

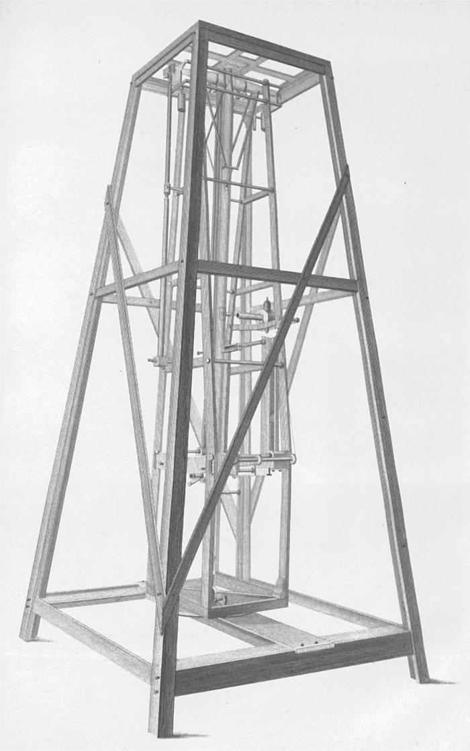

31. The instrument – a zenith sector – used during the Ordnance Survey’s meridian arc measurement.

A zenith sector consists of a dead-straight central frame whose vertical position is established by a plumb line. A telescope pivots on either side of this frame and the difference of its angle from the vertical can be measured in degrees on a scale at the frame’s base. To ascertain his latitudinal position, the astronomer reclined underneath this long, elegant, but cumbersome instrument and trained the telescope’s sights on the Pole Star, whereupon he recorded its angular difference from the vertical. A relatively simple

calculation

produced the angle of latitude from this observation. Upon Berge’s completion of the zenith sector, Mudge had taken his new toy to the Royal Observatory at Greenwich. There the Astronomer Royal, Nevil Maskelyne, who was something of an expert in these instruments, had willingly

proferred

‘advice and instruction’ about its use. His instrument completed, Mudge had then been left with the decision of where to position the

meridian

arc. Although he had desired ‘the most extensive arc’ possible through England, Mudge also knew that the nation’s variable landscape posed

significant

problems: hills could cause plumb lines to deviate from the vertical, as Maskelyne’s Schiehallion expedition had shown. So although an arc measured from Lyme in Dorset up into Scotland would have been very long indeed, the hilliness of the countryside through which it would pass had rendered it unviable. Instead Mudge had alighted on an arc stretching from Dunnose in the Isle of Wight up to Clifton, a small settlement about five miles south-west from the centre of Doncaster, positioned about 1° 13’ west in longitude from Greenwich Observatory.

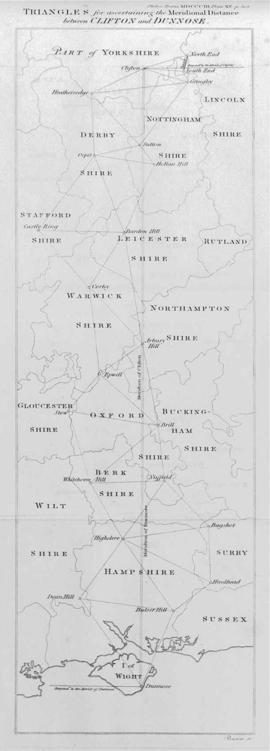

Between 6 June and 28 July 1801, Mudge had overseen the

measurement

of a baseline at Misterton Carr, at the most north-westerly point of Lincolnshire, near Epworth (where John and Charles Wesley, the founders of Methodism, were brought up). The base verified the accuracy of the

triangles

that proceeded along the length of the arc, from Dunnose to Highclere, Nuffield, Brill, Epwell, Corley, Bardon Hill, Sutton, Gringley and Clifton, many of which had already been measured for the Trigonometrical Survey. In May and June 1802, the zenith sector had been taken to Dunnose, and in July and August to Clifton too, to astronomically ‘fix’ the latitudes of the arc’s ends. Upon his project’s completion, Mudge had taken his zenith sector down to London to the Tower, where he had proudly shown it off to the President of the Royal Society. He had also taken this opportunity to exhibit ‘any Topographical Material in his office, which Sir Joseph Banks might be desirous of examining’.

32. The map of the triangles observed during the Ordnance Survey’s project to measure a meridian arc.

Mudge’s procedures during the arc measurement had been seemingly scrupulous. He had even ensured that the temperature was uniform at the top and bottom of the long zenith instrument, by opening ‘shutters in the roof, as well as the door of the observatory, a considerable time before the moment of observation’. By the end of the season, Mudge had been able to state ‘how thoroughly satisfied [he] was’ with the result: ‘the length of a degree on the meridian … is 60820 fathoms’, about sixty-nine miles. And he had been certain that the length ‘of the Arc, cannot but be determined with extreme accuracy’. After the completion of the project in 1802, Mudge had written up his methods and results and had read them before the Royal Society on 23 June 1803. His article had been subsequently published in the 1803 issue of the

Philosophical Transactions

and then afterwards as a separate volume. When the third volume of the

Account of the Trigonometrical Survey

was published in 1811, it included this earlier description of the meridian arc measurement that had taken place in 1801 and 1802.

The reappearance of Mudge’s article in the public domain provoked new interest in the endeavour, but not all of this attention was complimentary. On 4 June 1812 a paper by the Spanish geodesist Don Joseph Rodriguez, entitled ‘Observations on the Measurement of Three Degrees of the Meridian, conducted in England by Lieut. Col. William Mudge’, was read before the Royal Society. Rodriguez pointed out that the calculations that Mudge had obtained from his meridian arc measurement were

controversial

. Instead of confirming the accepted view that the earth was an oblate spheroid (i.e. flatter at the poles than at the equator), Rodriguez said that Mudge was suggesting the opposite, that the earth was an

oblong

spheroid, like an upright egg. Rodriguez voiced ‘a suspicion of some incorrectness in the observations themselves, or in the method of calculating them’. He was displeased, too, that Mudge had not made his procedure entirely

transparent

. He ‘had not informed us in his Memoir, what were the formulae which he employed in the computations of the meridian’, Rodriguez pointed out, and he compared Mudge unfavourably to his French counterpart, the

director

of the metre project, Jean Baptiste Joseph Delambre, who had ‘published and explained, with admirable perspicuity and elegance, all the formulae and methods’ of that undertaking.

Thomas Colby had joined the Ordnance Survey in 1802, in the midst of the meridian arc measurement. When the furore over Mudge’s calculations erupted in 1812, he proposed extending the arc from its termination near Doncaster up to the north coast of Scotland. He argued that a longer arc would provide more information about the earth’s shape over a larger area and might illuminate the confusion behind the earlier results. And as Mudge had described to the Commissioners in 1811, there were already plans to take the Trigonometrical Survey into Scotland, so the meridian arc extension could be measured simultaneously. In 1813, therefore, Colby set out for Scotland with a small team of assistants, to extend the arc to the

northernmost

edge of the British mainland.

Scotland presented more problems for the map-makers than England and Wales combined. Robert Kearsley Dawson, the son of the great Interior Surveyor Robert Dawson, was a member of Colby’s team and he recalled how ‘it was no uncommon occurrence for the camp to be enveloped in clouds for several weeks together, without affording even a glimpse of the sun or of the clear sky during the whole period’. The top of Ben Nevis was ‘almost

constantly

covered with mist, or deluged with rain’. In battering storms, and over sodden and bumpy ground, the soldiers attempted to push carts weighed down by surveying instruments, papers, tents and clothes, ‘by the application of guy ropes to support them, and with the men’s shoulders to the wheels’. During reconnaissance marches, the map-makers’ ‘resting places were often miserable hovels, and their only food the porridge of the country’. Even when successfully encamped, the tents frequently blew down during the night. At one camp, the nearest town where food could be procured and

letters

received and sent was twenty-four miles away. At times, when the rain set in, and the horizon hadn’t been seen for days, and the triangulation had come to a halt, it must have seemed as if it was all for nothing.

These hardships did not bother Thomas Colby. The resilient young man had grown up into an extremely tough 35-year-old map-maker. He travelled up to Scotland from London ‘on the mail coach’ and throughout five

continuous

days and nights of jolting, swaying, clattering, relentless motion, Colby took a rest of ‘only a single day at Edinburgh’ before continuing his journey north. For the length of the drive, he shunned the relative warmth

of the coach’s interior for a seat on the outside. It was said that ‘neither rain nor snow, nor any degree of severity in the weather, would induce him to take an inside seat, or to tie a shawl round his throat; but, muffled in a thick box coat, and with his servant Fraser, an old artilleryman, by his side, he would pursue his journey for days and nights together, with but little

refreshment

, and that of the plainest kind’. Upon arrival at his soldiers’ camp, Colby slept fully clothed, resting only ‘on a bundle of tent linings’.

Unhappily for his map-makers and assistants, Thomas Colby demanded the same hardiness from them. At first Dawson slept beside Colby, following his example, before realising that a colleague in a different tent had ‘put up his camp bedstead, and made himself much more comfortable – a lesson which I did not fail to profit by in my after experience’. But the most

gruelling

aspect of the surveyors’ time in Scotland was the extraordinary distances covered on foot. Relying only on a pocket compass and map and his own intuition, Colby eschewed paths and roads in favour of leading his team at a great rate, and as the crow flies, across ‘several beautiful glens, wading the streams which flowed through them, and regardless of all

difficulties

that were not absolutely insurmountable on foot’. We can imagine the surveyors struggling to keep up with the small, wiry map-maker over ragged grass and clutching gorse. During reconnaissance marches, Colby and his men would average thirty-nine miles a day. Over more prolonged periods of triangulation, he relaxed the pace to a mere twenty-seven miles. In one record-breaking trip through the tricky Highland countryside that lasted twenty-two days, Colby covered a magnificent 586 miles. Even Sundays were not guaranteed days off. On 25 July 1819 Colby led his men in search of a church. Failing to find one, he decided they should use the time to climb the 4049-foot mountain of Aonach Beag, near Ben Nevis. This ‘should have been our day of rest’, one hapless surveyor bemoaned.