Maphead: Charting the Wide, Weird World of Geography Wonks (37 page)

Read Maphead: Charting the Wide, Weird World of Geography Wonks Online

Authors: Ken Jennings

Tags: #General, #Social Science, #Technology & Engineering, #Reference, #Atlases, #Cartography, #Human Geography, #Atlases & Gazetteers, #Trivia

Which is why I tracked down Rodger. He seems unflustered by

his newfound claim to fame. “I knew the property was on the forty-eight-north line, but I had no idea about the—confluence, you called it?” But when I ask if I can visit the all-important square foot of land, I find out that it won’t be possible for months. Rodger is a cook on a tugboat currently bound for Hawaii and then Wake Island—one of the Travelers’ Century Club’s most troublesome destinations, if you’ll recall. “I’ll call you when I get back,” he promises.

I expect never to hear from him again, but two months later, Rodger’s as good as his word. “When do you want to come up and see 48/122?” he asks. That very weekend, he and I are out trampling the ferns at the end of his driveway, swinging our respective GPS receivers around like blind men with white canes. Just like geocaching, only without anything tangible waiting to be found.

“Near as I can tell, it’s right here,” says Rodger finally. “Zero zero zero. All zeroes.”

I wonder if I will feel some lightning crackle of Global Significance when I stand on the magic point, but nothing happens. I dutifully take a picture of the fateful ferns. Just as with the roadgeeks, attention must be paid.

“Do you feel like it’s an honor to be the caretaker of 48° N 122° W?” I ask Rodger.

He shrugs. “I dunno. It’s a two-edged sword. I might have to put up a sign at the end of the driveway now, so people can leave their phone numbers if they want to visit the spot.”

“What about a plaque?” I joke.

“Yeah, I thought about that . . .” he says quite seriously, stroking his chin.

On the winding forest roads back to the freeway, the stentorian British tones of my GPS device inform me that I’ve missed my turn-off. “You turned the wrong way, dumb-ass,” scolds Daniel. “Just do what I say.” I must have been distracted by the thought of thousands of confluence hunters combing the Earth for perfectly arbitrary geometric points. At least members of the Highpointers Club are climbing to real geographical peaks, albeit minor ones in many cases. The earth’s grid of latitude and longitude, on the other hand, is

entirely

arbitrary. The fact that we divide the circle into 360 degrees is an

ancient artifact based on the Babylonians’ (incorrect) estimate of the number of days in a year. Lines of longitude are even more arbitrary, since the Earth doesn’t have any West Pole or East Pole. Our current zero-degree line of longitude, the Prime Meridian through Greenwich, was a convention chosen only after much political wrangling at the 1884 International Meridian Conference, called by mutton-chopped U.S. president Chester A. Arthur. France refused to vote for the London line and continued to use its own meridian, through Paris, for thirty years. If the French had been a little more persuasive or the ancient Babylonians a little less, Alex Jarrett and his fellow confluence hunters would have a totally different grid of intersections to contend with.

But that’s the beauty of the Degree Confluence Project—its essential randomness. The photos on its website are just as homogeneous as the ones on any roadgeek site: the same unremarkable foliage and dry grass and mud seem to show up time and again, whether the magic spot was found in Botswana or Bakersfield. But the pictures remind us that it’s never enough just to

be

at a place—anyone can do that. The trick is to know where you are. Columbus “discovered” America, in his own small Eurocentric way, but when the continent was named, he was snubbed in favor of Amerigo Vespucci. That wasn’t just because Vespucci marketed the sexy natives better, I learned at the Library of Congress. It’s also because he was the one who knew where he was, knew the context. Columbus thought he was in India; Vespucci realized that a new continent had been found. By the same token, Rodger had probably passed those ferns on the way to his garage many times, but it was the Degree Confluence Project that “discovered” what they meant. That’s what maps are for: they provide the story of our locations and translocations. A $500 GPS device can tell you your position, but a $10 road atlas is still an infinitely more powerful tool for providing context.

The Degree Confluence Project isn’t the

reductio ad absurdum

of our new constant awareness of latitude and longitude. That honor would belong to the “Earth sandwich” dreamed up in May 2006 by the Web humorist Ze Frank. In a short video, Frank instructed his fans to place two pieces of bread on the ground at diametrically opposite

points, or antipodes,

*

on the Earth’s surface, making the Earth, in effect, into a giant if inedible sandwich. He even broke out a tender “Imagine”-style ballad to commemorate his brainstorm. “As I lay this bread on the ground, I know my job ain’t done,” he crooned, “but if the Earth were a sandwich, we would all be one. (Sandwich.)” Frank’s challenge was harder than you might think: looking at an antipodal map of the Earth’s surface reveals that almost every bit of land on the planet sits directly opposite a large body of water—almost as if the God of your choice always intended the sandwich version of His creation to remain open-faced! One of the few possible sandwich sites is the Iberian Peninsula: if you were to dig a hole straight through the center of the Earth from Spain, you’d reemerge somewhere in the northern half of the island nation of New Zealand. Just weeks after Frank’s challenge was posted, two Canadian brothers named Jonathan and Duncan Rawlinson, traveling from London to Portugal, made a side trip into the hills of southern Spain to lay a half baguette on the dusty ground, while an Internet co-conspirator did the same thing near his home in Auckland, New Zealand. The first Earth sandwich in human history had been completed.

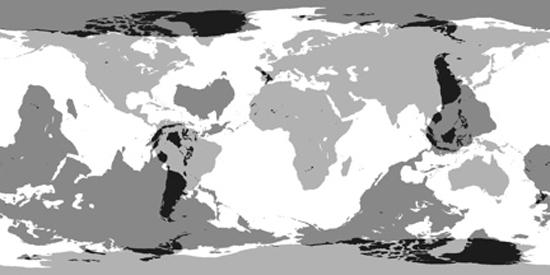

The Earth, overlaid with its antipodal version. Very few spots are sandwich-friendly in both hemispheres.

It’s easy to dismiss

the Earth sandwich

as a silly (if ambitious) prank, the kind of conceptual art that the Liverpool cult band Echo & the Bunnymen practiced in the 1980s, when they would include odd locales like the Outer Hebrides of Scotland on their tour itineraries, so that the tour would form

the shape of a rabbit’s ears

when seen on a map.

*

But as I reflect on the map freaks I’ve met on my journey, one of the things they all share is this same urge: to make the Earth—the entire Earth, its meridians and parallels and antipodes—into a giant plaything. Systematic travelers use jet planes and geocachers use GPS satellites and Google Earth fans use 3D-rendered aerial photography, but the impulse is the same one that’s led people to pore over atlases for centuries: the need to place our little lives in the context of the Earth as a whole, to visualize them in the context of a grander scale. To this day, when we outline some ambitious plan, we still speak of how it will put us “on the map.” We crave that wider glory and perspective.

We also crave exploration, and that’s a thrill that’s become scarcer as technology has advanced. When Alexander the Great saw the breadth of his domain, he wept, for there were no more worlds to conquer. Well, actually, I don’t know if he did or not. That’s a quote from Alan Rickman’s German terrorist character in

Die Hard

. But the sentiment, at least, is true enough: human ambition requires new frontiers to cross, and for the last millennium, most of those frontiers were geographic in nature. In 1872, a surveyor named Almon Thompson explored the high desert plateaus of south-central Utah, mapping

a tributary of the Colorado called Potato Creek, which he renamed the Escalante River, and a thirty-mile mountain range now called the Henry Mountains. Thompson didn’t know it, but his discoveries would be

the last river and the last mountain range

ever added to the map of the contiguous United States. Before Thompson’s expedition, travelers had referred to the Henry range as “the Unknown Mountains,” and Navajo in the area still call it Dzil Bizhi’ Adini, “the mountain whose name is missing.” But that’s not true anymore: now all is named, all is neatly catalogued, just as the mapmakers thought they wanted. That frontier is gone.

Of course, the human yen for advancement didn’t end when Conrad’s “blank spaces” on the map were gone. We have turned our attention to “mapping” other things, like outer space and the human genome, but for those of us hardwired to organize the world spatially, cartographically, something is still missing. We’re not content with discovering things that must be fuzzily visualized—quarks and quasars. We wish we could still discover real

places,

places we could visit, places that could surround us.

And so we reinvent exploration, albeit on a smaller and less perilous scale. We find ways to make even the most banal places new—by organizing them into made-up checklists, by planting geocaches in the parks there, by photographing the exit signs of the highways running through them, by studying their pixels in unprecedented detail on the Internet. Others forsake tidy modern maps altogether. Some recapture a sense of mystery with antique maps, with their wildly inaccurate coastlines and tentacled monstrosities at the margins. Others wander paths that are still unexplored because they exist only in the imagination. When I was a child, I could always add to a completed map of some fantasy kingdom simply by Scotch-taping a new piece of paper at one edge and continuing to draw. There will be no depressingly final “Potato Creek” on these inexhaustible maps.

It’s been therapeutic for me to meet so many different kinds of geo-nuts. I can see that their rich diversity of obsessions all seem to be expressions of the very same gene, and it’s the same instinct that made

me an atlas collector at the same time that all my friends were more into He-Man and

Knight Rider

. But I’ve been most surprised by the response from friends who find out what I’m writing about. Since childhood, I’ve expected people to snort at the idea of maps being a bona fide hobby, so when I say, “It’s a book about people who like maps,” it comes out like an apology. Instead, those turn out to be the magic words that make me a secret confidant, a father confessor.

Laurie Borman, the editorial director at Rand McNally, said to me, “When I tell people where I work, you wouldn’t believe how many people tell me, ‘Really? I

love

maps!’ It’s more than you would think. But you can tell they think it’s sort of an embarrassing confession to be a map geek.” That’s exactly what I find from my friends as well—even ones I’ve known for years, ones I’d never expect to be closet map fans.

“I can kill a whole afternoon just looking at rare maps on dealers’ websites,” says one friend. I knew he worked from home, but I had always naively assumed he was actually getting some work done sometimes. “Just drooling, not buying. It’s like porn in our household.”

“When my marriage was going south,” says another friend, recently separated from his wife of five years, “I took my collection of

National Geographics

from when I was a kid and threw them away, like my wife had been telling me to for years. But I couldn’t bring myself to throw away the maps, so I took them out and hid them on top of the bookshelves.”

*

“As a kid, I’d beg my parents for the

Thomas Guide

every Christmas,” yet another friend tells me, lowering her head and smirking guiltily at the sordid shame of it all.

The unlikeliest map booster of all turns out to be Mindy’s obstetrician, whom I call the “monkey doctor,” since, in addition to having delivered my daughter, Caitlin, she also delivers all the gorilla babies at Seattle’s Woodland Park Zoo.

†

The monkey doctor keeps a world

map mounted on the wall of her exam room, because, she says, nothing distracts nervous patients better than a map does. I’m not sure this is the highest bar for map love to clear—“Maps: More Fun Than Thinking About an Imminent Pelvic Exam!” is unlikely to catch on as a geography slogan anytime soon—but the doctor has been surprised by how many patients (“more than you’d expect!”) she finds completely engrossed in the map when she comes in.

Despite all the scare stories about American college students who can’t find Africa on a world map, it seems there is a vast untapped reservoir of goodwill toward geography out there. It goes undercover; it keeps its head down until it knows it’s in friendly company. But those alarmist newspaper articles about map-dumb kids wouldn’t be written

at all

if, on some level at least, our society didn’t still feel like maps were an important marker of knowledge and culture and interest.

I’m convinced—and relieved—that, as a maphead, I’m not the lonely oddity I always thought I was. But this is even better news for the world at large: people still like maps! Despite the media fear-mongering, our kids still like maps. If they’re failing geography tests en masse, it’s only because

we’re

letting them down. We’re not teaching geography or spatial literacy the right way or giving them a long enough leash to explore their environments on their own. We’re inadvertently convincing them in a million little ways that maps are old-fashioned and dull and that there’s something a little weird about looking at them for fun.