March Toward the Thunder (11 page)

Read March Toward the Thunder Online

Authors: Joseph Bruchac

As lovely as that melody was, it was deadly as shot and shell.

It rallied the nearly beaten men out of retreat. Shouting that anthem of Southern patriotism, defiant against all invaders, the inspired Rebels began to advance. The Union soldiers fell back before the terrible beauty of a song.

Louis rubbed at his left hand.

Why is this bothering me?

He turned his hand up to look. His palm was black and blistered.

Why is this bothering me?

He turned his hand up to look. His palm was black and blistered.

If M'mere were here

, he thought,

she'd make me a poultice for this. Or she'd just pluck some wide hairy leaf, like from a bandage plantâmullein. The one some call flannel leaf. Then she would have me walk around all day with it clasped in my hand. And by the time night came, the leaf would be almost gone and my hand would be well

.

, he thought,

she'd make me a poultice for this. Or she'd just pluck some wide hairy leaf, like from a bandage plantâmullein. The one some call flannel leaf. Then she would have me walk around all day with it clasped in my hand. And by the time night came, the leaf would be almost gone and my hand would be well

.

No matter what it was, whether a fever or a cut or a sick stomach, his mother always knew the remedy. Not one from a box or a bottle, but from the medicine plants themselves. M'mere. He closed his eyes, trying to find her in his memory. And there she was. He saw M'mere as clearly as if she were there beside him. Her back to him, her medicine bag slung over her shoulder, she was kneeling to speak words of thanks to a large-leafed plant. It wasn't one that Louis remembered seeing before, though it did look a bit like mullein. But the leaves were darker green and there was a fuzzy blue flower at the end of a leafy stalk. His mother pulled free a large leaf from the base and turned toward Louis, smiling as she held it out to him. He lifted his hurt hand. Then the throb of pain from his palm made him blink.

And in that blink of an eye the vision of his mother vanished. Louis found himself back looking at his injured palm.

When did I get this burn?

As soon as he mouthed those words he remembered. The Confederates had only been able to push them back to the other side of the entrenchments. There the advance had stalled, but the fighting had not. Divided by only a single rampart, Blue and Gray struggled back and forth. More Union troops tried to push into the gap. But they were packed too close. No one could get through. Men screamed as they fell and were trampled into the bloody red muck by the milling mass of soldiers trying to push forward. Among them, Louis remembered seeing the faces of their two drummers, Bing and Bang. Boys whose real names he'd never known, disappearing under the boots and bodies. He tried to reach out toward them, but it was no use. They were lost in the tangle of legs. Then, in the midst of that madness, Rebel gun barrels began to bristle through every loophole in the breastworks to explode at point-blank range.

Louis nodded.

That was when.

That was when.

A rifle had been thrust through at his face. To save himself, he'd grabbed the barrel, pushed it up and away. Near red-hot from firing again and again, the steel had burned his palm, but the ball had missed himâthough the blast made his head ring as if he'd been swatted by a giant. As that empty rifle pulled back, he raised his own Springfield and fired it through the same notch in the headlog.

“Keep it up,” an officer next to him shouted. “We're bringing up more ammunition. Hold the line.”

By the side of men whose names he would likely never learn, shooting at enemies whose faces could not be seen, Louis reloaded and fired.

And held.

At last, deep into the night, a bugle sounded from the other side of the embattled line. Those Gray soldiers who could still stand, walk, or crawl fell back, dragging wounded and dead, fading into the darkness.

Days later, Louis read a newspaper account of the battle. They called it the Bloody Angle. The cost to both sides was 12,000 men.

Louis's mind and heart ached as he tried not to remember the song that had stirred those Gray soldiers to such fearful bravery. But it kept going through his head. Perhaps it would be there for the rest of his life, that bittersweet melody about a bonnie blue bloody flag.

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

MAIL

Saturday, May 14, 1864“Dedham?”

No answer.

“Smith?”

No answer.

“Page?”

Silence again

, Louis thought.

, Louis thought.

Sergeant Flynn, a bandage around his left arm that matched the one on Louis's right, stood alone as he called out the names. Both of his corporals were among the missing. Along with their two noncoms, half of E Company failed to answer. Killed like Possum and Happy and Scarecrow or so gravely wounded they'd never fight again. Like Knapp and Kinney and Bishopâthe three of them minus enough arms and legs between them to fill another man's complement of limbs. Or missing like Corporal Hayes and Ryan, lost in the mud and the mist. Dead, dying, being held prisoner? No one knew for sure.

Who's left? Just me, Sergeant Flynn, Bull, Songbird, Joker, and . . .

“Merry?

“Here, sir!”

His small friend with the face of a child had proven tougher than many soldiers twice his size.

Sergeant Flynn paused at the end of the roll. He looked slowly at each and every face.

“Me boys,” Flynn began. Then he let his hands fall to his sides. “I've no fine words for ye. Jes' take some time t' yourselves while ye can.”

They looked at one another as Flynn walked slowly away. Then Merry wandered off, leaving just the four of them sitting there. Devlin, Belaney, Kirk, Nolette.

Devlin cleared his throat.

Was he going to raise a song?

Was he going to raise a song?

Instead, Songbird pulled a deck out of his pack. “Cards?”

There was a long, tired silence. Then Joker sighed.

“Poker. Sounds good to me about now. Especially when the joker's wild. How about you, Bull?”

“Arrh,” Belaney replied, “poker's ta game me pa told me to fear like ta devil. But after ta last few days, the devil seems tame t' me. Deal me in!”

The three of them turned to look at Louis.

“Come on, Louis,” Songbird said. “Naught to lose but the pay we've yet to see.”

“More fun than a toothache,” Belaney added.

“Yeah, Louis.” Kirk nodded. “Play a hand or two with yer mates.”

My mates

, Louis thought. He took in each of their faces. Mates, indeed. Brothers despite the fact that he was Indian and they were not.

, Louis thought. He took in each of their faces. Mates, indeed. Brothers despite the fact that he was Indian and they were not.

I'd give my life in a fight for any one of them. And I'm not about to let them see me cry. And just now not a one of them called me Chief.

He raised up his hand. “Maybe later,” he said, standing and walking away before they saw the tears in his eyes. He wasn't sure where he was headed. But then someone called from farther down the trench.

“Louis, Louis!” It was Merry beckoning to him, pointing.

A covered wagon was pulled up on the small dirt track behind their trench.

“Come on,” Merry said, tugging at Louis's sleeve. “There might be a letter for you from your mother!”

His small friend was smiling as he hurried toward the horse-drawn covered wagon with the letters

U.S. Mail 2nd Corps

printed large on the canvas.

U.S. Mail 2nd Corps

printed large on the canvas.

The first smile I've seen in days.

The day before Louis had come upon a man from the 28th Massachusetts sitting next to his best friend's body in a ditch, cap in hand. Every now and then he would turn his head up toward the sky and laugh out loud. But there was no joy in that bitter laughter.

Merry, though, was pleased to the point of being giddy.

How can anyone smile now?

Louis stopped to kick mud from the soles of his boots.

But who am I to judge? I hardly know how I feel these days from one moment to the next, unless it's just plain confused. And maybe there is mail for me from M'mere.

The thought of mail or even a package from home could bring a smile to many a soldier's face. Despite the dangers and difficulties of war, nothing seemed to stop the weekly arrival of the mail. Even the gumbo of the Virginia roads that bogged down most other freight had not been able to prevent the arrival of the lighter mail wagon pulled by two big draft horses. It was even more welcome than the paymasterâwho had yet to show up during the month and a half Louis had been in the army.

Six weeks. Is that all?

Yet he felt at times as if he'd been a soldier forever, wearing itchy and ill-fitting clothing, scratching at fleas and lice, almost breaking his teeth on the so-called bread that was hard enough to put a dent in a man's skull. One joke running through Second Corps was that by the evening of the fight at the Bloody Angle, Company C had run out of ammunition. So they'd started hurling hardtack and the enemy had panicked and run.

Other times, though, other times I can't believe I'm here.

Just two nights before the battle he'd woken up in confusion. Where was he? Out in the little camp in the woods where he went to cut the trees to make their baskets?

Toni, nigawes?

Where are you, my mother?

Where are you, my mother?

Gradually, it came to him. He was farther than the other side of the moon from the poor but peaceful life he had known.

Writing or receiving letters were his only real connections to that distant life an innocent boy had once lived. That was why he wrote so regularly to his mother, even though stamps, which didn't have any weight to them like a coin, cost a dime. He passed up sweets from the sutlers' wagons to buy those little pieces of paper that would insure his words got carried safe to his dear mama.

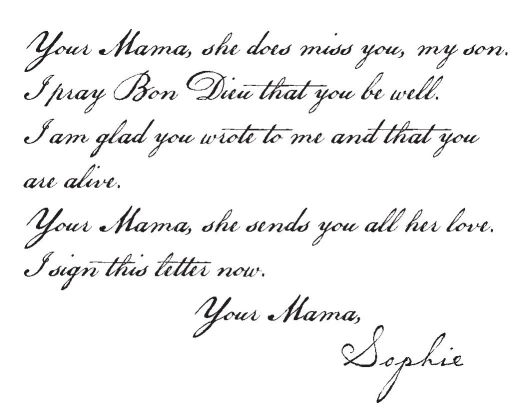

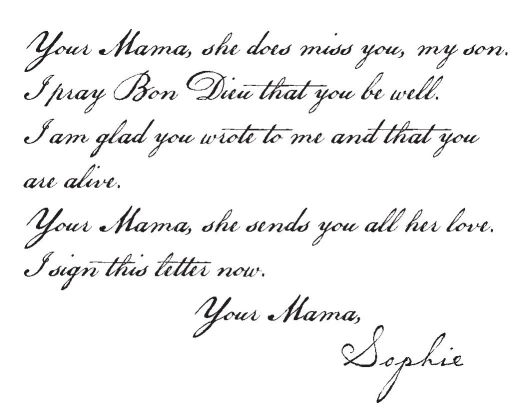

He'd received just one letter thus far from M'mere. The wording was clearly hers:

But the writing in pen with florid curlicues was nothing like the laborious printing that marked his mother's hand. She must have paid someone to take down the words as she spoke them.

Simple as those words were, Louis read a whole world of meaning into them. He carried her letter in the pocket closest to his heart.

Mail. Is that why Merry is so happy today? Does he think he's going to get mail?

Louis shook his head.

That can't be it. Didn't Merry tell me that he enlisted in secret? No one in his family, especially not his brother, knows where he is.

Louis shook his head.

That can't be it. Didn't Merry tell me that he enlisted in secret? No one in his family, especially not his brother, knows where he is.

Suddenly Louis knew. He grabbed his friend's thin shoulder, spinning him around.

“You saw your brother!”

Merry danced away from Louis's grasp. His face was now bright with excitement.

“Yes,” Merry said. “Oh yes! In the afternoon, during the battle, I was no further from him than I am from you. And Louis, it was like my dream. I protected him. I shot my musket at an enemy soldier who was taking a bead on him. I don't know if I hit him or not, but the man was gone after the smoke cleared, and Tom was safe. And Tom knew I'd done it. He turned right to me and thanked me for saving his life.”

“Was he angry because you were there?”

Merry blushed. “He didn't recognize me. How could he? I mean . . . he'd never seen me before in a uniform. My face was black and dirty. I didn't say anything for fear he'd know my voice. If he'd known who I was he would have tried to protect me and risk his own life. When the fight was done, I made my way back here to our company.”

Merry's voice choked. He grabbed Louis's sleeve again and tugged hard at it. “Do you understand?”

Louis wasn't sure that he did. But he nodded his head anyway.

The two of them had reached the mail wagon. As always, Louis went first to the horses. Others tried to shove into line to ask if there was anything for them or to be close enough to reach out right away if their name was read off of a letter or package. But not Louis.

At least one man ought to let these horses what have worked so hard know they are appreciated.

He ran his hand along the neck of the big white mare on the right.

“You're a fine faithful girl,” he said as the horse lowered its head toward him.

Merry, who'd been at his side, suddenly choked back a sob. The little private walked swiftly away, wiping his face with his sleeve.

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

ANOTHER INDIAN

Sunday, May 15, 1864The Lord's Day seemed to make little difference to those who were running the war. One day for killing was the same as the next. This Sunday, though, seemed destined to be a quiet one.

We're both worn out

, Louis thought.

Blue and Gray alike.

, Louis thought.

Blue and Gray alike.

Morning services had ended no more than an hour ago, but he couldn't recall a word the chaplain spoke. He raised his face up to the noon sun, shining down brightly for a change.

Be thankful,

he thought. The old words his father taught him came back to his mind.

he thought. The old words his father taught him came back to his mind.

Ktsi Kisos, okeohneh

.

Great Sun, thank you for shining down on me

.

.

Great Sun, thank you for shining down on me

.

May, but warm as a summer day in August back north. If it weren't for the throbbing in his burnt hand, he might have been able to imagine himself back there.

Other books

The Red and the White: A Family Saga of the American West by Andrew R. Graybill

Tangling With Topper by Donna McDonald

Miranda's Revenge by Ruth Wind

So Close the Hand of Death by J. T. Ellison

Heart's Desire by T. J. Kline

Son of Our Blood by Barton, Kathi S.

How by Dov Seidman

Rules by Cynthia Lord

Slow Burn (Book 2): Infected by Bobby Adair

The Sahara by Eamonn Gearon