March Toward the Thunder (27 page)

Read March Toward the Thunder Online

Authors: Joseph Bruchac

She pressed his forehead again with her hand, rose, and was gone.

But I haven't grown well and strong again.

Louis shook his head in near despair. He'd been getting weaker every day since The Angel's visit. He slid his hand, which was too heavy to lift, down toward his leg.

No doubt about it. Hot to the touch.

Plus his nose had begun picking up a smell from his wound.

The doctor looked graver than usual as he did his customary painful poking and prodding.

Louis heard the words he spoke to one of the nurses as he walked away.

“I haven't the time now to do it, but that leg will have to come off this afternoon. It won't take long. Fifteen minutes at the most.”

I'd rather die

.

.

A wry smile twisted his face.

With this doctor's care I probably will.

He began to think about his death.

What will it be like? Will I walk the road of stars that leads up into the skyland? Will I see my father again? Will one of those angels that Father Andre spoke to me about come down and open its great white wings to embrace me? I wish .

. .

. .

But Louis never finished that thought. The sound of a commotion reached his ears.

“You cannot . . .”

“You're not allowed . . .”

“Madame!”

“

Nda! Allez!

You will not stop me.”

Nda! Allez!

You will not stop me.”

“Hands off the lady,” a second voice said.

Louis knew that second voice. It was Artis. It made his heart leap, but what filled him with even more joy was that he had also recognized the woman's voice he heard first.

Only one person in the world could sound as fierce and loving as that or speak such a mix of Indian and French and English. Another sort of angel had just arrived for him.

“M'mere,” Louis sobbed as Artis helped him to sit up. Then he was in Marie Nolette's strong arms.

CHAPTER THIRTY-FIVE

HEALING

There was no logical wayâas far as white man's logic wentâ for his mother to have known he needed her. No one had written her a letter about his injuries. No one sent a telegram to the Indian mother of one insignificant private.

Yet her long journey south began on the day Louis fell at Reams Station.

When I called for her to come and help me.

“The trees,” M'mere said. “They tell me you need me. So I come.”

Things have to be done according to the rules in the army. Regulations have to be followed. Louis had learned that in the months he'd been a soldier. But even the army found it hard to resist Marie Nolette. After marching across four states carrying a bag nearly as big as herself on her back, she was not about to be deterred by rules, regulations, or those who thought they could enforce them when faced by one small French Canadian Indian mother.

The first one she confounded was the doctor. As M'mere held Louis, he returned with his saw and two attendants to carry Louis to the operating table.

M'mere snatched the saw from him and threw it on the ground!

“You man with dirty hands!

Nda!

You will take my head before you touch his leg.”

Nda!

You will take my head before you touch his leg.”

As the doctor and his two helpers backed off from his mother, who looked more like a female wolverine than a human, Louis caught a glimpse of Jake, the male nurse. Jake grinned like a jack-o'-lantern and held up both thumbs.

The next was a corporal who tried to explain that there was no way a mother could just sweep in and take her son with her. Although a patient, Private Nolette was still a soldier.

“And you have used him up,” Marie said. “Now you go to cut off his leg. So what use will he be as a soldier? Him you do not need. You give him back to me.”

Louis watched openmouthed. He hadn't realized how well his mother could speak the English language that she always said stuck in her throat like a fish bone.

The cowed corporal was replaced by a sergeant who ended up shaking his head and going for a lieutenant. By now a crowd of soldiers on crutches, nurses, and orderlies had formed around the tent.

“I will stay here to fight for my son if it take me all summer!” Marie Nolette said, standing beside his cot and crossing her arms on her chest. She turned to wink at Louis to let him know her choice of words had been no accident.

“You tell him, ma'am!” a soldier leaning on two canes shouted out from the bandages that covered most of his face.

“They ain't gonna back her down!” a one-armed private chipped in, pumping his remaining fist in the air.

A loud

Hurrah!

went up from the crowd as the befuddled lieutenant retired from the field of battle. This was the best entertainment that had ever come to Depot Hospital.

Hurrah!

went up from the crowd as the befuddled lieutenant retired from the field of battle. This was the best entertainment that had ever come to Depot Hospital.

My mother!

There was so much hope and pride in his heart now that Louis thought it might burst. He was grinning as widely as all the others who'd gathered to take his mother's side.

The captain, who was the last to arrive, came with a handful of papers.

Louis's mother took half a step forward, her chin up, her index finger raised. Before she could speak, the officer raised his hand in a conciliatory manner.

“Mrs. Nolette,” the captain said, in an extremely polite voice, “we've looked into your son's records. He's due to be honored with several commendations, it seems. Wouldn't you like to see him stay here to get his medals?”

“You want him to have medals, you send them to him, eh?” Marie Nolette pressed her lips together and nodded.

The captain nodded back to her.

The man is trying not to laugh. He's smart enough to be as amused by this as everyone elseâexcept that sawbones.

Louis could see the doctor out of the corner of his eye. Clearly displeased, he'd been pushed to the back of the crowdâhopefully holding the dirty saw he'd retrieved from the muddy tent floor.

“In that case,” the captain said, handing the papers to Louis's mother, “if you accept the consequences of removing him from professional hands, we're placing your son in your care.”

The captain produced a pen. “Just make your mark here, ma'am.”

Artis helped him to his feet, wrapping a blanket around his shoulders. Louis's head was spinning even more than it had been from his fever. People were cheering, patting him on the back, grasping his hands.

“Good luck to you, laddie.”

“'Bout time somebody on our side had a victory.”

“Your ma'd make a better general than the sorry lot we been saddled with!”

Then they were in the sunshine outside the tent, Artis supporting him with an arm around his shoulders on one side, M'mere under Louis's arm to his left.

“

Nigawes,

my mother, I have no clothes for traveling.”

Nigawes,

my mother, I have no clothes for traveling.”

“In my bag,” Marie Nolette replied.

A cheer went up from somewhere behind the tent they'd just left.

Louis turned to look. Near the back of the crowd Jake cupped his hands to shout to Louis.

“Had a little ac-cy-dent back here. Doc fell into the sinkhole!”

The elation that gave him strength began to fade as they moved away from Depot Hospital. They were on one of the roads now that led up from the river.

Don't know if I can take another step

.

.

A wagon pulled up next to them.

“Sorry I'm late, ma'am,” a bearded wagoneer said to Louis's mother.

Artis slipped his arm from around Louis's shoulders. “Grab hold.”

Louis grasped the side of the wagon to steady himself.

His mother wrapped her arms around Artis. Louis could see from the surprised look on his Mohawk friend's face how much strength Marie Nolette was putting into that hug.

Bet she cracked at least two of his ribs

, Louis thought as his mother let loose and Artis took a deep breath.

, Louis thought as his mother let loose and Artis took a deep breath.

His mother whispered a few words and then put something in Artis's hand. He nodded and slipped the medicine she'd given him for protection into his pocket.

The tall Mohawk boy turned back to Louis.

“Far as I go, brother,” Artis said. He squeezed Louis's shoulder and stepped back. “You travel well. Your ma will take care of you. From what I have seen of her, she can cure everything except that bad case of the Abenaki uglies you got.”

Artis looked up for a minute, took a deep breath, then reached down to his belt. He untied the bag of marbles and placed them in Louis's hand. “I'll win these back from you after the war.”

Then Artis walked away without looking back.

Should of told him that no Abenaki ever beat a Mohawk in an ugly contest.

But the moment had passed. Artis had taken his leave in true Indian fashion.

We don't have words for good-bye

.

.

“Climb on,” the yellow-bearded driver said.

As soon as they were settled in, his mother cut off the moist dressings.

“Wet bandages! Fools! Do they not know you must keep a wound dry.”

She reached into her bag and brought out a flask filled with brown liquid.

“Drink,” she said.

Louis drank, warmth spreading from his throat through his chest. He breathed in and out, each breath bringing him a little more strength.

His mother held out a pair of moccasins. She helped him pull off his boots, threw them into the back of the wagon as he put the soft moose skin slippers on his feet. He lay back and his mother wrapped the blanket around him.

It was dark when the wagoneer dropped them off in the countryside.

Where are we? These woods look as thick as it was in the Wilderness.

His mother helped him down. Easier to walk with moccasins on his feet, though his leg ached some. She led him along a barely visible trail through the brush. It came out in a large clearing. Canvas-covered huts made of brush and bent saplings were mixed in with small log cabins in a circle around a central fire.

“Nidobak,”

his mother said. “Friends.”

his mother said. “Friends.”

People with brown faces came up to them. Some wore clothing made of skin. Others were dressed like Southern farmers.

Indians

, Louis thought.

, Louis thought.

Their words sounded like Abenaki, but the accent was strange. He was led into a cabin, placed on a bed.

An old man, his face as lined as a map, looked at the open wound in his leg, the one that smelled of gangrene. He and M'mere nodded heads in agreement.

The old man went outside. When he returned it was with a bark cup that he handed to M'mere. She carefully reached in, began to place the contents of the cup along the edges of the wound in his thigh where flesh had begun to rot. Small things the size of white beans. They squirmed as she held them. Maggots.

The old man patted Louis's shoulder, said something in Indian. Because of the accent, it took Louis a minute to understand.

Clean good. Eat sickness away

.

.

He nodded and closed his eyes.

A deep, loud sound woke him.

Cannons!

He sat up from his blankets, heart pounding, reaching for the rifle that should have been by his side. But his Springfield wasn't there.

Where?

His mother's hands grasped his shoulders, gently pushing him back down.

“The fever, she is gone,” M'mere whispered. “

Oligawi.

Sleep good.”

Oligawi.

Sleep good.”

Louis relaxed. He remembered where he was.

Not guns. The rumble of thunder

.

.

A smile came to his lips. Things on this earth were continuing as the great good spirit Ktsi Nwaskw meant them to continue. Despite wars and all the foolishness of men, the Thunder Being, who cleansed the earth from evil, was walking again across the sky.

CHAPTER THIRTY-SIX

ABOVE THE TOWN

As Louis sat in the bent wood chair he'd finished making that morning, he looked out over the land. Fields and woods and in the distance the blue haze of the Green Mountains of Vermont. What M'mere had said in her letters had turned out to be true. Fishing was good in the pond. Pickerel, perch, bullhead. The farm had fine fertile ground for growing corn and beans and potatoes. Plenty of good trees. And this view . . .

You surely can see a wide swath of God's Creation from the top of Cole Hill.

It was especially beautiful today, now that the first frost had touched the sugar maples. The land was a patchwork of gold and scarlet sewn in among the green of pine and spruce and cedar and hemlock. He looked at the crutches leaning against the wall of their small cabin. A spider had set up shop between them. The harvest of dried fly carcasses at the bottom edge of the web showed that it had been doing good business at its prime location for some time now.

Louis stretched out his leg. The scar pulled a little, but his limb was as strong as it had been before.

Fit to chase down a deer by the moon when the leaves fall

.

.

As he thought that, a feeling of guilt swept over him.

He walked to the southeast corner of the porch. At night the valley below was dark save for a few scattered lights from farmsteads. Louis thought back on those nights when he'd looked from high places to see the glow of countless thousands of army campfires, the lights of the Rebels' camp across the line like a reflection.

I pray to God I never see such a sight from this hill

.

.

He touched the hip pocket where he'd put the letter. It arrived for him at the post office in the Greenfield General Store a week ago, but he'd just picked it up yesterday.

M'mere must have told him where he could reach us.

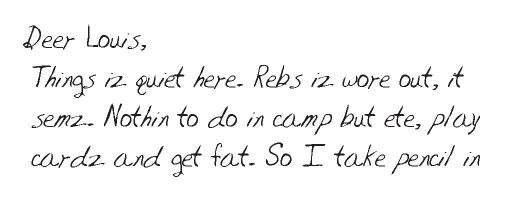

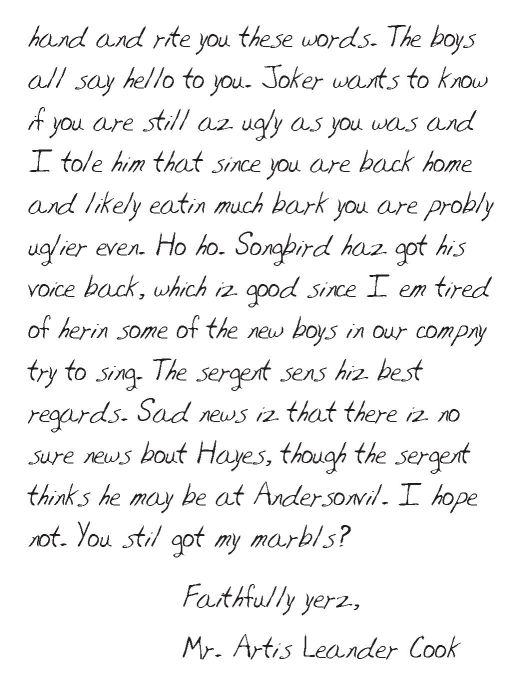

Louis pulled it out, unfolded it, and read it for the tenth time.

Other books

The Christmas Knight by Michele Sinclair

The Park Service: Book One of The Park Service Trilogy by Ryan Winfield

Death Rides the Night by Brett Halliday

Prescription for Desire by Candace Shaw

The Eye of the Hunter by Frank Bonham

Eden's Garden by Juliet Greenwood

The Village Vet by Cathy Woodman

Street Dreams by Faye Kellerman

Love at First Bite (Book 1 Just a Little Taste Series) by Jade, Scarlett

As You Wish by Jennifer Malin