Maria Callas: The Woman Behind the Legend (56 page)

Read Maria Callas: The Woman Behind the Legend Online

Authors: Arianna Huffington

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Composers & Musicians, #Entertainment & Performing Arts

To the soprano who has just gone through Gilda’s “

Caro nome”

: “Gilda is a passionate girl, you know; you must convey to the audience all her palpitating emotion before you even begin to sing. The very act of breathing is an emotion.”

To a tenor slightly lacking in intensity: “Come on now, Mario. More passion. You are a Neapolitan, you have no excuse.” But when he made to embrace the soprano, she instantly interrupted: “No gestures! With the

voice!

”

To a Korean baritone singing the Prologue from

Pagliacci

: “You have a big voice there; let it out . . . I don’t care if you crack on the top note, but hit it hard. Caruso cracked many times.” And not just Caruso. But only once did Maria allow her pupils and the audience into her own private agony. A young soprano had just finished singing Aida’s

“O patria mia

,” and had made a bit of a mess of it. She turned to Maria to explain: “There are three or four notes I just can’t manage.” “Likewise,” was Maria’s reply, and the self-mocking smile did not stop the shivers from running down everyone’s spine.

When she was asked once what was the greatest key to performing music well, Maria had replied, “You must make love to it.” Yet when a student soprano at Juilliard neglected the trills in a Verdi aria, Maria stopped her.

“Where are those trills?”

“Do I have to do them?” pleaded the girl.

“Could you imagine a violinist or pianist,” she snapped, “even a beginner in this conservatory, refusing or unable to perform those written ornaments? He would be thrown out, considered incompetent. With singers, it is no different—whatever they might think.”

This combination of technical mastery and musical passion was what made Maria unique. But could this secret be communicated? For that matter were the Juilliard master classes the opportunity for music’s retired High Priestess to pass on her wisdom and her secrets to the younger generation? Or were they a safe way for the greatest dramatic singer in the world to try out her strength in public, illustrating her teaching by singing but without running the risk of being judged? There is no doubt that, although Maria became totally involved with her pupils, she did see the master classes mainly as an attempt to break through her terror of singing in public by doing so as an extension of teaching onstage. And there is no doubt that most of the notables in the audience, from former colleagues to the new general manager of the Met, were there not so much to hear Maria’s advice on interpretation as to hear Maria demonstrate her advice.

“Suddenly,” wrote Richard Roud, “during the

Butterfly

duet, one heard a ghostly third voice—Callas singing along with the soprano. Then, like something out of the past, that magnificent voice welled up. Like the curate’s egg, however, it is magnificent only in parts. A phrase of five or six notes comes out with all the black velvet splendour of the old days: then without warning it goes. Like some ancient tapestry there are patches where the colours are still bright, where the gold threads still gleam, but there are others where it is so threadbare that you can see right down to the warp and woof.”

Despite all the caveats, Maria did get from the Juilliard master classes the simple confirmation that she could once again face the public without the paralyzing panic of the last years of her career. But she could not have enough reassurance; she wanted another opinion. Michael Cacoyannis happened to be in New York at the time producing

Bohème

, so she arranged to sing just for him one afternoon at the Juilliard theater, which she had booked in great secrecy. “She asked me to sit somewhere where she couldn’t see me,” recalled Cacoyannis. “She was nervous and apologetic. ‘I’ve just come back from the dentist,’ she explained, ‘so I’m not in very good voice. . . .’ ”

It is a haunting scene. The great Callas, nervous as at her first audition, singing in an empty auditorium for one man, a friend who she knew cared for her, but who nevertheless she wanted hidden somewhere in the dark, so that she could not even feel him there, even though, blind as she was, she would not have seen him; and yet eagerly, anxiously, waiting for his opinion, for reassurance. “You can do it, Maria,” he said.

There were not many left who believed that she could. She asked Peter Mennin, the head of the Juilliard School, whether

he

thought she could do it. “It was an honest question, and it deserved an honest answer,” he remembers, “so I said no. The room she had been working in with Masiello was acoustically very good, a room that flattered the voice. This and the response she got during the master classes had encouraged her too much. But demonstrating a phrase beautifully is not the same as carrying off a whole evening.”

In March 1972, the master classes were drawing to a close, and the future lay barren ahead of her. George Moore, president of the Metropolitan Opera board, very unexpectedly had offered her the job of artistic director at the Met. She was sufficiently interested to spend a lunch hour at the Oak Room of the Plaza, discussing with Schuyler Chapin, then manager of the Met, the dreadful state of opera houses. But no more. It was around this time that di Stefano came back into her life. The last time they had sung together was on December 22, 1957, the last night of

Un Ballo in Maschera

at La Scala. “Maria, let’s come back together,” he said now, and he said it again and again. Maria never answered no right away, even when she had no intention of ever saying yes, but in this case she had a much greater investment in the discussions. For a start, she dreaded the emptiness stretching ahead once the master classes were over. Even more important, in terms of reliving her old triumphs, di Stefano was infinitely better than a hundred pirate recordings. He was like a walking embodiment of her glorious years. All the old animosities, fights and walkouts melted in the warmth of reliving their past together. Di Stefano’s tenor voice was one of the best of the century, but the animal intensity with which he sang had very quickly worn it out. “What is so exciting about him,” someone had said in di Stefano’s heyday, “is that he is dying as he is singing.” By the time he met Maria again, his career had rather ingloriously petered out. It was a curious match, grounded in weakness: di Stefano, musically dead for years, feeding off Maria’s legend, and Maria, consumed with fears, feeding off his raw Italian bluster which at first she took for strength. Deeply lonely, Maria let herself drift into a relationship that gave her some joy but mostly caused her great pain. Di Stefano was married and, according to Maria’s strict moral code, one does not have affairs with married men. What made it even harder was that di Stefano’s wife—another Maria, as it happened—was someone she knew and liked. As always for Maria, when action and belief diverged, guilt closed the gap. She remained, right to the end, extremely secretive about their relationship, and only to her godfather did she write openly and freely.

Their match was rooted in the past, but di Stefano was determined that it would at least have a professional future. The first attempt was a recording made in London at the end of 1972 with Antonio de Almeida conducting. The greatest secrecy shrouded all the arrangements. Until the last moment the London Symphony Orchestra did not even know who the soloists would be. Verdi and Donizetti duets were recorded and rerecorded. There were many problems, one of them being that di Stefano seemed unable to sing except at full volume. But they were all determined to perform the miracle, and slowly, patiently, resurrect two of the century’s greatest voices.

On December 4, a few days after the recording sessions had begun, Maria heard the news of her father’s death in Athens. He was eighty-six years old, and by then nearly blind. After his marriage he had returned to live in Greece, and had become even more remote from Maria’s life. So she felt all the more strongly that she had left unfinished business with him, and now he was dead. She felt a warmth for him she had not often experienced in the last few years, and this intensified her grief. She remembered once, when she was a child, walking with him in New York. She wanted an ice cream but would not ask for it. She stopped in front of the ice-cream vendor and pulled her father’s jacket, but she would not ask. And when, then and later, she longed for his attention and tenderness she still did not ask. Nor did he. So they met mainly on her first nights, but rarely connecting, by then both finding it hard to give or to receive tenderness. And the rift his remarriage had caused seemed now so unnecessary.

His death had another effect, in many ways much more painful. It opened the doors to the greatest of all the remaining items on the agenda of her life—her relationship with her mother. “I would never make up with my mother, and I have very good reasons,” she had said a year earlier. “She did many wrong things to me, and blood is just not that strong a tie. I don’t feel I have to act and say ‘Mother darling.’ I just can’t fake.” It was by no means so clear-cut. Her resentment was one side of the equation, her guilt was the other. When the buzz of the world had subsided, the guilt recollected in solitude became too intense, too uncomfortable, to be ignored. She still could not bear, as she said, to “make up” with her mother, but she needed to do something to exorcise the guilt, so she began sending money. Evangelia saved all the pink receipt slips from the bank as though they were love letters. And in a sense they were; or if not love letters, at least they were the first evidence of a thawing in the relationship.

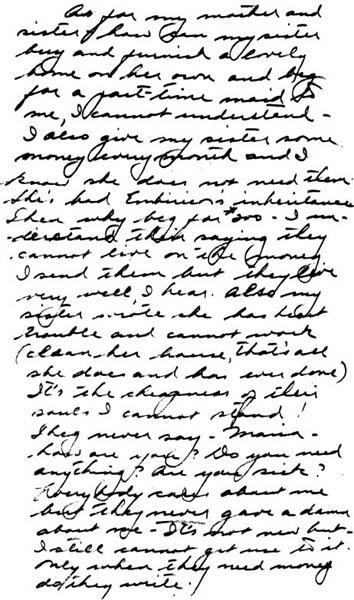

Maria’s conflicts with her family came up in one of her most pained, incoherent and contradictory outbursts to John Ardoin, beginning with a reference to a recent letter from her sister. “But when you have a family and that family kicks you like mad . . . And then on top of it she says of Mamma’s growing, Pappa’s growing, older, you know. Now what would you feel like? I could strangle that girl, girl—a woman of over fifty. You tell me that they’re growing older. Well, of course they’re older, so am I, everybody’s growing older. So what do we have? Four homes isolated, mine and three of theirs. Miserably alone. At least I have accomplished something that is true. But why should I have accomplished something alone, and why should I now be alone at home when we all should be, all four of us, one helping the other? . . . Not the least thought. A revolution happened in Paris. Do you think my parents called or my sister? Not one. My friends called, admirers who don’t even know me, from London, from Italy. My ex-maid, my ex-cook called me. That makes you think, you know . . .” And seven years later, in August 1975, after Jackie’s perennial fiancé, Milton Embiricos, had died of cancer, she came back to the same bitter theme, and even some of the same bitter words, in a letter to her godfather (see

page 320

).

There is not one word from Maria on the subject of her mother and her family spoken from any position other than that of the victim. Her unconscious longing to end the division with her family became much more intense and conscious when there was no longer any hope of having a family of her own. And yet she did nothing, and indeed thwarted all attempts, to bring them together. The longing was real, but the fear was no less real; nor is the paradox so hard to understand. If Maria had been reconciled with her mother, she would have had, for the first time, to stop blaming her for everything in her life, and this would have started the process of ending one of her most persistent and self-destructive patterns. There were very many things for which she could blame her mother, just as there was a lot of truth in her complaints about Meneghini, the Rome opera house management, Ghiringhelli and Rudolf Bing. But her sense of having been victimized and her underlying self-pity became a poison running through her life and corroding everything long after the events themselves or the actual harm done. “God, I’m still feeling the result of Rome,” she said in 1968, exactly ten years after her Rome walkout. “I could not go on with the performance, I could not be killed that way. It would be stupidity. If I had my vocal possibilities, if I hadn’t been sick, I would have stood there. I’ve done that thousands of times at the Scala, everywhere. I’m famous for having defended myself well. The tigress, they call me. But do I need to be crucified? I didn’t have my voice. It was slipping all the time, with an aggressive public. And so forth and so on, and this and that, and my mother and now him. I’ve got to sit back and take it and try not to say anything, for whaever I do say will be to my disadvantage. Whatever I say, it will be undignified for me, not for them. Who cares? So I don’t have even one friend. Why?”

This outburst, which puts Maria in the center of a hostile world out to do her harm, to betray her, to “crucify” her, sums up the way she perceived reality. “Only my dogs will not betray me,” she said in the last few months of her life. By the end, these convictions had become a veil which would not allow her to experience or even see anything that contradicted them. What she looked for she discovered, what she expected she brought to pass; yet toward the end, the same woman who had against all odds made herself everything that she had become, was seeing life as something that happened to her, and herself as at the mercy of others, as the victim of their hostility, their incompetence, their dishonesty. And this in turn increased her pain, her anger and, above all, her fear.