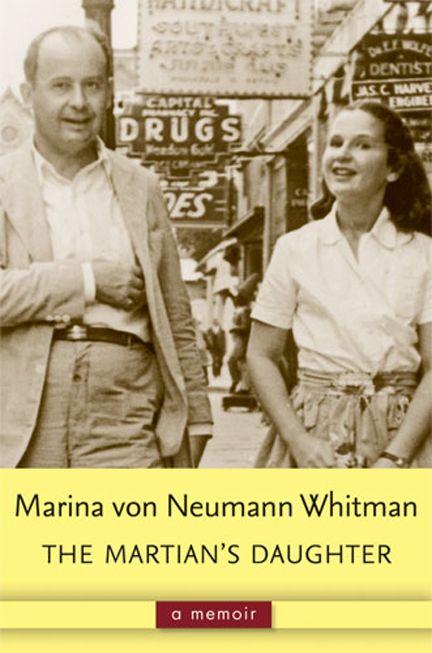

Martian's Daughter: A Memoir

Read Martian's Daughter: A Memoir Online

Authors: Marina von Neumann Whitman

A Memoir

Marina von Neumann Whitman

The University of Michigan Press

Ann Arbor

Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2012

All rights reserved

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher.

Published in the United States of America by

The University of Michigan Press

Manufactured in the United States of America Printed on acid-free paper

Printed on acid-free paper

2015 2014 2013 2012 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Whitman, Marina von Neumann.

The Martian's daughter : a memoir / Marina von Neumann Whitman.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-472-11842-7 (cloth : alk. paper)—ISBN 978-0-472-02855-9 (e-book)

1. Whitman, Marina von Neumann. 2. Economists—United States—Biography. 3. Jews—United States—Biography. I. Title.

HB119.W4W44 2012

330.092—dc23

[B] 2012005031

For

Will & Lindsey

The rising generation

On whom, as always, the hope of the world rests

This memoir would never have come into being were it not for unremitting pressure from my dear friend, Susan Skerker. When mere words were ineffective, Susan combined the nimble mind that had brought her to the executive level at one of the nation's leading automotive companies with her tireless typing skills to coax out of me the seventy-six pages of stream-of-consciousness memories from which this book was born. From there, it was the investigative prowess of three research assistants, James DeVaney, Christine Khalili-Borna, and Google, that filled in the vast gaps in my memory. The two human assistants were, at the time, students in the Master's in Public Policy Program in the Gerald R. Ford School at the University of Michigan. Christine was at the same time a candidate for the JD at the University of Michigan Law School, and the search skills honed at the

Michigan Law Review

enabled her to unearth references that I feared would remain forever undiscovered. Funding for research assistance was provided by the Gerald R. Ford School of Public Policy and the Stephen M. Ross School of Business at the University of Michigan; both schools have my thanks and appreciation.

The list of people who responded to the myriad questions with which I peppered them during the writing process is so long and varied that I am bound to have left some out; to them I apologize in advance. The ones that remain in my notes are, in alphabetical order, William Bowen, Robert Chitester, Gerald Corrigan, Ernest Courant, Paul Courant,

Edwin Deagle, Robert Durkee, Freeman Dyson, George Dyson, Paul Ericson, Géza Feketekute, Tibor Frank, Frank Giarratani, Marc Good-heart, Ann Halliday, Martin Liander, Micheline Maynard, Paul McCracken, Mustafa Mohatarem, William Pelfrey, Craig Perry, Karl Primm, Mary Procter, Deborah Purcell, Edward Rider, William Rhodes, Albert Sobey, Maryll Telegdy, Linda Weiner, Edward Wuntsch, and my brother, George Kuper.

Several expert friends gave me invaluable editorial advice that guided the numerous revisions this book went through before it took final shape. They are Nicholas Delbanco, Sylvia Nasar, Philip Pochoda, and, above all, Leonard Downie. My editor at the University of Michigan Press, Tom Dwyer; his capable assistant, Alexa Ducsay; and my own indefatigable administrative assistant, Sharon Disney, all provided invaluable skills in steering this book through the publication process. Finally, my beloved husband and life partner, Robert Whitman, not only helped me with recall and gently corrected many faulty memories but also, though legally blind, struggled through multiple versions of the manuscript, improving virtually every sentence and paragraph as he went. It is Bob who, above all, gives meaning to the title of my concluding chapter, “Having It All.”

For the past decade, my ninety-four-year-old father, who is a Muslim from Central Asia, had one question and one question only for me: “Is your book almost finished?” All conversations with him ended with an injunction to “Finish it soon!” For as far back as I can remember my father's ambitions for me dominated our relationship. Perhaps partly because he was an immigrant to this country, his hunger for his children's success was greater than theirs. My adolescent vision of the future involved marrying “a rich man who'll let me sit around and read all day.” My father, I later learned, dreamed of my becoming a

New York Times

reporter.

When I did become, more or less by accident, a journalist many years later, Marina Whitman was already the chief economist at General Motors and one of the few women at the top of the economics profession. The book in your hands is an evenhanded, if often wry, account of what it took for a woman to succeed in a man's world one generation before feminism and the Pill helped to break the male monopoly on the best jobs. It is also a coming-of-age saga about a young woman who wanted it all in an era that insisted that women must choose between work and family. Most of all, it is a moving story about fathers and daughters and what they want from and for each other, in particular the tension between a father's desire to mold, protect, and live vicariously through his daughter and the daughter's equally strong determination to develop a mind and life of her own.

The Martian of the title refers to John von Neumann, Whitman's father and arguably the most important mathematical mind of the twentieth century. Pampered, precocious, and rich, fond of strong drinks, dirty jokes, and fast cars, von Neumann was one of the geniuses who joined the Jewish exodus from Hungary in the 1930s and, in 1933 at age twenty-nine, joined Albert Einstein at the newly founded Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton. For the next twenty-five years, von Neumann was involved in and responsible for some of the biggest mathematical and scientific breakthroughs of the century: game theory, the bomb, and the programmable computer.

Considered the smartest man alive and capable of concentrating on mathematical problems in the middle of raucous parties, von Neumann hardly fit the popular stereotype of the abstract thinker perfectly at home in the crystalline world of ideal forms but hopelessly lost in ordinary life. True, his wife claimed that he didn't know where ice cubes came from, and he often read weighty books in the bathroom, but he dressed like a banker, preferred the company of generals and politicians to that of academics, and displayed an exceptional talent for dealing with large bureaucracies and running large projects. Moreover, he was not afraid of making decisions or taking a stand. He chose A-bomb targets in Japan, advocated a preemptive attack on the Soviet Union, and was the most influential member of the Atomic Energy Commission. At the time, in the treacherous atmosphere of the McCarthy years, he avoided the political blunders that wrecked the careers of other science stars like Robert Oppenheimer and Edward Teller.

“It doesn't matter who my father was, it matters who I remember he was,” Anne Sexton, the poet, once observed. Rather than recalling the public figure, Whitman focuses on the private man. For all his charm and generosity, however, he comes across on these pages as a man who never learned to feel comfortable in close proximity to other human beings and for whom intimate emotional terrain would always remain an alien environment. When Whitman's mother, the beautiful, hot-tempered, socially ambitious Mariette, left him for one of his graduate students, taking their two-year-old daughter with her, he was more puzzled than heartbroken. He remarried quickly, within a year of his divorce, impulsively choosing a woman he met on one of his visits back to Hungary

and who he hardly knew. Klara Dan turned out to be unstable, as well as neurotic, and von Neumann spent the rest of his life mystified by her fluctuating moods and frustrated by his inability to placate her fears and jealousies.

One of the most intriguing aspects of Whitman's upbringing concerns the unusual child custody arrangement with his ex-wife that von Neumann insisted on. In what was either a modern experiment in child rearing or a bow to the traditions of the European elite, Whitman was to live with her mother until she turned thirteen. Then, having reached the age of reason and capable of benefiting from proximity to genius, she would live entirely with her father in Princeton until she went off to college. She would be Eliza Doolittle to his Professor Higgins.

Judging by the outcome, the experiment was a success. Whitman flourished intellectually and socially in Princeton. While her stepmother could be difficult, her father showered her with affection, advice, and more tangible tokens of his esteem such as furs and cars. Whitman responded by working hard at school and winning admission to Radcliffe. Once there, she proceeded to get straight As, including in a calculus course. Relieved that she had not besmirched the von Neumann reputation for mathematical prowess, she declared her formal education in that field over.

In her senior year, Whitman announced that she intended to marry a young English instructor immediately after graduation. Her mother, who had long feared that Whitman's brains and intimidating pedigree would discourage suitors, was delighted, but von Neumann was devastated. His frantic appeals, which Whitman quotes at length, are a testament to the depth of his misgivings, and fears that she was closing off any chance of a significant career or, for that matter, material comfort. She liked money too much to be content on the salary of an academic, he warned her.

By then von Neumann was dying. He was fifty-three, confined to a wheelchair, the great head riddled with cancer, the lightning-fast brain barely able to calculate the sum of two single digits. When Whitman visited him in the hospital, she was overcome with grief and guilt. Another girl might have canceled the wedding. Whitman would not. However much she had absorbed her father's values, she had a mind of her own, and enough backbone to stick to her guns.

It was a good thing. In 1956, when Americans were marrying young, having babies, and moving to the suburbs, von Neumann could not possibly have foreseen the seismic changes that would make it possible, less than twenty years later, for President Nixon to appoint a female economic adviser, or for the country's number 1 company on the Fortune 500 to appoint a woman to a highly visible position on the management team. Mostly, though, he simply underestimated the emotional intelligence that let his daughter fulfill her own dreams as well as his.

Sylvia Nasar

Tarrytown, New York

July 8, 2011