Martin Marten (9781466843691) (2 page)

Read Martin Marten (9781466843691) Online

Authors: Brian Doyle

This was how Dave’s dad talked, sort of scholarly but blunt. Dave’s dad was a decent guy, although he was a real stickler for domestic and academic responsibilities. Dave’s mom was not quite such a stickler that way, but she was a total stickler for kindness and tenderness toward Dave’s baby sister and respect and reverence for everything else alive, as she said. We are omnivorous mammals, and so we are designed to have to kill and eat certain of our fellow beings of every shape and sort and size, but we will do so with respect and reverence for the inestimable value of that life we are taking in order to aid and abet our own lives, as she said. And we will make a concerted effort to not only defend life against those who would take it without respect and reverence but encourage and seed life where and when we can, which is why she planted flowers and vegetables all around the cabin and in any and all sunny spots nearby and volunteered one afternoon a week at the raptor recovery center on the other side of the mountain and stood up at town meetings and school board meetings to remind everyone that clean water was the paramount gift and virtue of their region and that their clear duty as residents was to defend clean water against any and all attempts to foul rivers and creeks and lakes. This was how Dave’s mom talked, passionately but simply, and when she stood up to speak she sounded tall, thought Dave, even though she was hardly five feet tall and getting smaller by the year.

* * *

The last person in the cabin I want to tell you about is my sister, says Dave. She is five years old, but she is one advanced being, that’s for sure. She rambles widely. Her name is Maria. She is almost six years old. Her birthday is next week. She does not talk much, but she sees little things in the woods that no one else sees. She too is now allowed to roam on her own outside the house, but she has four markers past which she must not go, cross her heart. One is the big rock that looks like a hawk, which is as near to the highway as she can go. One is the huge red cedar tree that might be a thousand years old, which is as deep into the forest as she can go. One is the copper beech tree that someone planted many years ago, which is as close to the river as she can go. And the fourth point on her campus is Miss Moss’s store, which is as far down our road as Maria can go. She signed a contract with Dad about all this, and she knows if you sign your name, then you are bound to keep your word. She has short red hair. She sleeps late in the morning but then stays up at night looking at books and drawing maps. She says her greatest ambition is to be me. I point out that she cannot be me inasmuch as I am me, and she says

we will see about that, Dave

. I say for one thing I am male and she is female and she says

maybe those are just labels, Dave

. This is how she talks when she talks at all, which she does not do so much. But she hears and sees everything, that kid. You wouldn’t believe the things she sees when we walk in the woods. She found a bear claw one time stuck in a tree in a place where I had been leaning for ten minutes and never saw it. She has found deer antlers and animal bones and baby birds in nests and arrowheads and one time a hunting knife so rusted with what we thought was blood that our dad took it to the police station down the mountain in Gresham, just in case. One time she even found a pair of sneakers frozen solid inside a chunk of ice when we were up on the mountain past Timberline Lodge in winter, and how she saw those in the ice remains a mystery to this day, for they were new white sneakers inside a white block of ice among a pile and jumble of blocks of ice fallen off the Joel Palmer Glacier. Joel Palmer was one of the first white people on the mountain, and there’s a story that his moccasins wore out as he climbed over the peak in winter, and he had to come down over the glacier barefoot. Maria says those sneakers must be Joel Palmer’s sneakers, and he didn’t want to get them wet, maybe, because they were so shining new. Our dad thawed them out and dried them carefully, and now they sit on the shelf over the fireplace with a card explaining how Maria found Joel Palmer’s sneakers. See, a card explaining the exhibit for visitors, that is the sort of life we lead in our cabin. In our family, we leave room for the possibility that someone will come in and wonder about the new white sneakers above the fireplace, and if that happens, why, then, we are prepared for that.

ONE NIGHT,

years before, late in the autumn, about a mile south in the deep woods from where Dave and Maria and their mom and dad live, a terrific windstorm on the mountain snapped off the top half of a vaulting Douglas fir tree. This fir tree was at that time more than four hundred years old and had grown in such an inaccessible ravine that it had never been logged before the national forest was established in 1893, so that even when it lost a hundred feet of height and its entire bushy canopy, even though it was now a ragged snag that looked sort of naked and forlorn, it still soared a hundred feet into the crisp air of the ravine, way up where only the ravens and falcons flew.

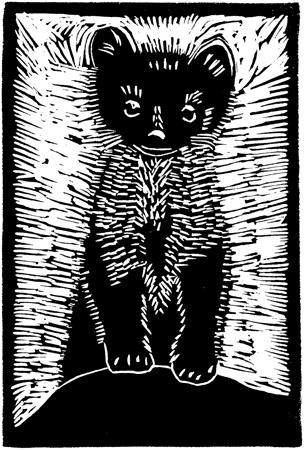

Year by year, as the tree slowly died, it was hammered and hollowed by all sorts of animals, from the smallest borers and beetles to the largest woodpeckers, and three times it was hit hard by lightning, which shivered and rattled it something fierce. Finally, about halfway up the trunk, what had been a small cavity became a fairly roomy hole, really a small wooden cave, about two feet deep by two feet wide. For a few years the hole was a nest for various birds; then it was taken over by a family of flying squirrels for several years; then it was the home of the owl who ate the squirrels; and then, after quite a long stretch of that owl’s family and descendants, it had been commandeered by a lean brown animal called a marten.

This particular marten was a mother who knew that she would soon deliver her kits, and she had been looking for weeks for the exact right den for this momentous event; she had examined burrows and caves of all kinds, from stone caves at the timberline to the abandoned burrows of foxes to the hollow logs in which skunks love to live, but none offered the defensible safety, sturdy walls, scope of grim maternal vision, and essentially weatherproof environment that she sought until she found the fir snag one moist spring morning. She evicted the badly frightened young owl who thought he had a perfect right to the hole inasmuch as it had been in his family for several generations, and she spent the next three days lining it properly with moss and fern and grouse feathers. When she was done, her only regret was that she did not have owl feathers, the previous occupant having left the hole too quickly to have contributed significantly to decor.

And in that wooden cave this April evening there is a birth; and then another, and then two more; until finally there is an exhausted mother, delighted but weary, and four tiny squirming nearly naked marten kits, none of them bigger than your thumb. The first three born are males, and the last, the tiniest, female. For a moment, after the last kit is born, she struggles with her larger brothers to find room to suckle; but then the brother born right before her shoves their older brothers aside to make room for the baby, and she too savors the first rich milky meal of her life. On and off for days and days the kits suckle and sleep, sleep and suckle, their mother dozing and occasionally rising to stretch and poke a wary nose out the front door.

Down below their tree, the snow melted, even in the shadowed parts of the ravine, and bushes sprouted new green fingers, and trees awoke from their long slumber, and all sorts of mammals and birds and insects found the doors by which their new generations entered this wild world; and there came a momentous day in late May when the mother marten led her four glossy kits, now the size of fists, headfirst down the fir to the redolent and seething wilderness below. She went first, showing her progeny how to grip lightly with their razor claws and walk confidently on the dense bark; the third brother, the one who had been kind to his sister, brought up the rear. Though he was the youngest of the brothers, he was noticeably the largest, and he seemed nearly twice as large as his sister. Tiny though she was, she learned quickest and was the only one of the four who did not tumble into the ferns at the base of the tree; instead, she leapt as lightly and deftly from the tree as her mother, while Martin, the youngest of the brothers, rounded up the other two and cuffed them back into line behind their mother. And so it was the five marten made their way to the river through an astonishing new world of trees and rocks, songs and whistles, bushes and scents, mud and flowers, all bathed in the high thin light of a mountain afternoon in spring. You could write a thousand books about this first walk alone, but of this opening adventure, Martin would remember only this one event: a honeybee rumbled by, and the oldest of his brothers leapt and snapped at it, and the bee stung the kit exactly between his teeth and his nose so that his upper lip swelled to epic proportions, and the kit could not suckle his mother for two days, so there was that much more milk for the other three, who enjoyed the largesse with a deep and humming pleasure as their brother moaned and bubbled and bemoaned the flying dagger it had been his misfortune to investigate.

DAVE’S DAD WAS A SORT OF LOGGER,

as he said. He worked with two other men in a little three-man company that did selective logging on the mountain on contracts from the State of Oregon and Clackamas County. They also did a whole slew of other jobs, like hauling timber after forest fires, and maintaining and replacing signage in the national forest, and hauling drivers out of ditches after blizzards on the mountain, and helping repair bridges and washouts after storms and floods, and so many more things that if we listed them all, this page would go on for a week. Dave’s dad also volunteered at the library in Zigzag once a week and occasionally did a little yard and carpentry work for people who needed it done but did not have any money, like Miss Moss. Dave’s dad pretty much worked all the time, even on Sunday around the cabin doing this and that and the other thing, but he never made a fuss about it or seemed to sweat or move fast, and he always had time to sit and answer questions or stare at woodpeckers for a while if that’s what needed to be done. What with Dave’s dad’s several jobs and Dave’s mom’s job in laundry services at the lodge, we seemed to have just enough money to get by, says Dave, if nobody got sick or broke anything and the car kept working.

Then my dad lost his job, says Dave.

Dad says that he didn’t lose it, exactly, says Dave. He says that he declined to further participate in suspicious activity which he believed to be not only unjust but illegal. This is how my dad talks, even in a moment like this, when he is explaining to my mom at the table why he lost his job. It turned out that the two men he worked with had signed contracts to do work that Dad says is clearly against the law, not to mention poor business for the citizens of the mountain of every shape and stripe, and when he made his feelings known, the other men said grimly,

in or out, Jack,

and Dad said grimly,

out,

so he is out. Mom says she is proud of his decision and supports him without reservation, but her face is haggard, and she is asking to add Saturdays and probably Sundays to her job at laundry services at the lodge. Maria and I have talked about what we can do for money, and she says she will have to think about this more before she can come up with a plan, because she is not yet six years old, and perhaps turning six will afford her some new ideas. I myself, said Dave, have decided to snare birds and rabbits to eat, and then when the snow comes, run a fur-trapping line. I have read a lot about fur trapping, and I think a young man with some experience in the woods should be able to make a small profit, if he approaches the task with caution and diligence and persistence. If I prepare thoroughly this summer and scope out the right places for traps and familiarize myself with the lives and habits of the animals in question, I think I can be of material assistance to the family, which certainly, despite the fact that no one is talking about it, needs help.

* * *

There is a store in Zigzag that sells every single possible small important thing you could ever imagine you could ever need, if you lived on a mountain far from the flurry and huddle of stores in the city. In this store in Zigzag, you can buy string of every conceivable strength and fiber. You can buy traps. You can buy arrows. You can buy milk and cookies. You can buy tire irons and shoehorns. You can buy false teeth and denture glue. You can buy comic books and kindling. You can buy apples and pork tenderloin. You can buy kale and rock salt. You can buy explosive caps for removing rubble from a precarious situation. You can buy saws and drill bits. You can buy nightgowns and shotgun shells. You can buy old cassette tapes, and you can order iPads and iPods, which Miss Moss will have for you next week at the earliest, a phrase she much enjoys using for all sorts of things, only some of them having to do with the store; Dave remembers when he was little and asked Miss Moss when the sun would come up the next day and she said distractedly,

next week at the earliest

. Miss Moss also claims that she can order iGlasses and iWash, although no customer has as yet ordered those things. She once with a totally straight face told a small boy that, yes, she could order an iPanther, the most interactive mountain lion app imaginable, but it would not arrive until next week at the earliest.