Martin Marten (9781466843691) (22 page)

Read Martin Marten (9781466843691) Online

Authors: Brian Doyle

Pause. Another thing Mr. Shapiro had learned in his years as a teacher was to at least try to stay calm and count to ten, although he noticed he never actually got all the way to ten; eight was his personal record.

Look, Dave, he said, I am not stupid, and I know things have changed since you were in my class in sixth grade. I get it that you are now a teenager and close to being a man. But the guy everyone liked for his friendly kindness then seems to have abandoned ship. I am here if you need help. Being a teacher is more than grading. And you must know that I am not the only teacher or student to wonder why you are so curt and rude these last few months. I just got here, as you know, but your other teachers here have mentioned it to me.

Dave opened his mouth and closed it and opened it again and closed it and sat there simmering. What could he say? He had nothing to say. He was angry and ashamed and annoyed and angry. He just wanted to be who he wanted to be. He didn’t want to be what anyone else wanted him to be. Everyone had an idea of him and he was none of those Daves. He just wanted to be left alone and people were always after him to be something or do something. Couldn’t people just leave him alone? What was so hard about leaving a guy alone when he wanted to be left alone? Was that so hard?

Dave?

I have to get home, Mr. Shapiro. If we don’t have practice, I have to get going.

There being nothing more to say, Mr. Shapiro said nothing, and Dave grabbed his stuff and left, yanking the door shut just hard enough to say something without saying anything, and Mr. Shapiro stood by the window and stretched for a while like the therapist said he should every day but he didn’t.

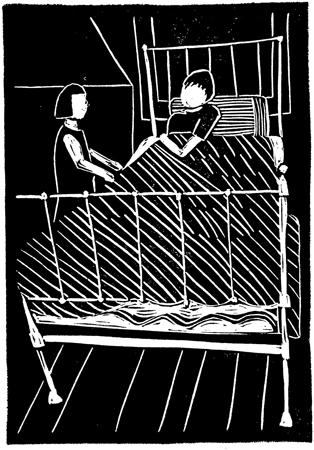

But all the way home, Dave felt a shiver of shame for the way he had spoken to Mr. Shapiro, and when he and Maria were in bed that night and she said

what’s the matter

, he told her, and she got out of her bed and padded over to his and hung her face an inch over his face and said

be tender

, and then she padded back to her bed. You know how when you are going one way in a river, and you stick your paddle in and hold it in the right spot for a second, and the whole boat turns? It was like that for Dave after that. Years later he would tell his own kids about those two words from their aunt Maria at that exact moment and how those two words woke him up and cracked something, and this is one of the thousand reasons why your aunt Maria is so cool, although all three of you already know

that

, don’t you?

RIDING AN

OLD

HORSE

through a forest is a lot easier than riding a

young

horse in the woods, said Mr. Douglas to Miss Moss, raising his voice a little so she could hear him clearly, although he was talking frontward and she was sitting behind him on Edwin. Because your older horse, for example Edwin, knows not to be rushing along headlong but rather to meander and pick and plod his way along and not be knocking his companions off his back with untoward branches and things like that.

Meander

is a lovely word, said Miss Moss. That’s a dollar word.

Thank you.

As is

untoward

. You hardly ever hear that word.

Thank you.

Are we allowed to be riding a horse in the national forest?

Yup. Nor does Edwin leave, ah, evidence. He saves that for home.

A meticulous being.

It’s more that he doesn’t like conducting his toilet outdoors, I think.

Ah.

Like most of us.

Ah.

Although he is meticulous about many things.

Such as?

He likes his hair brushed a certain way.

Ah.

God help us if you brush it any other way. He gets sulky.

Ah.

And he likes his food served a certain way.

Such as?

Mash cooked just so, with honey. You forget his honey, he lets you know about it right quick, and in no uncertain terms, neither. And it has to be a

quart

of oats—no more, no less.

Two

carrots, not one or three. And he’s not much for walking in the rain. Snow he doesn’t mind, but good luck getting him out in the rain. He just doesn’t see the point of moist. There have been times when I needed him to drag someone out of a ditch in a thunderstorm, and he just takes refuge in metaphysics. He’s an obfusticator. He gives you that look, you know, and then you know you are in for an

hour

of debate. It’s like living with a theologian.

How did you and Edwin meet?

Blind date.

Pardon me?

Edwin was a police horse in the city, you see, and they were just about to retire him, and my date and I went down to meet her brother, who was the policeman who had ridden Edwin, to pick him up, the brother, to give him a ride to dinner where we would meet

his

date, and that’s how I met Edwin. He was just standing there, and we became friends, and I worked out a deal with the policeman. He was happy that Edwin would be up on the mountain. He said Edwin had always liked the mountain but that he, the brother, had never had occasion to get up there with him.

Did you see your date again?

No.

Why?

To be honest, Ginny, I didn’t like the way she used her beauty as a tool. I didn’t like that at all. It seemed selfish and sort of cruel.

What did Edwin think?

Of what?

Of your date.

I don’t think he liked her much, either, but unless you are dealing with food or hair or rain, it’s hard to get a clear opinion from him. He keeps a poker face. I mean, I have known him for years, and I have no idea what he’s thinking right now.

* * *

This is what Edwin is thinking: When are you going to ask her again? It’s past time. Are you going to sit up there babbling about hair and rain or are you going to get down on your knees and ask the poor girl to marry you or what? If it was me, I would be down on my knees already instead of rattling on and on about oats and policemen, you silly oaf. You asked her the once, and she declined, but she didn’t decline permanently. Do you not remember the way she declined? She declined as gently and mildly and sweetly and affectionately as you could ever possibly decline an invitation to marry. That no was about as close to yes as you can get with a no. Me personally I thought she was gently closing the front door and flinging the back door open. Me personally I would be down on my knees as soon as we came across a dry place to kneel down. Do you think a being like her comes along more than once in a lifetime? I could tell you stories of the beings I know who never met the being they should have spent their lives with or spent their lives with the wrong being or mated with the wrong being and had to pay for that mistake the rest of their lives. Do you think you get many chances to ask this sort of question of this sort of being? In fact, if you do not kneel down, I will damn well kneel down and get the whole thing started myself as soon as I find a dry place. As if there’s a dry place on this mountain in May. The only dry places are probably caves or sun-soaked meadows or the hollows of old trees like the one Maria slept in. Fine—the first cave I come across or the first hollow tree or the first high dry sunny meadow I see, I am going to kneel down and make it clear that this is the time and this is the place and this is the person. Fine.

* * *

Maria’s final assignment in first grade, the big spring project due at the end of May, was to portray her domicile, in a medium to be chosen by you, the student. You can, said the teacher, write, paint, draw, sculpt, video, build a model, or portray, in any other form or manner you like, the place where you live. This is a Creative Project, so I am not going to tell you what to do. But I do want you to think about it first, and then work hard at it, okay? Don’t leave it for the night before and make your mom do it or just copy what your older siblings did in this class. Part of this project is to get you ready for next year, when you will be asked to do more work on your own, and part of it should be just fun, a way to see your home in a different light. The one thing I will ask is that you think of your home as a verb, not a noun—think of it as a thing in motion, not just a place. Do you see what I mean? I am more interested in what

happens

inside your home than in the actual building. Think about that for a while before you do your project.

And Maria did think about it for a long while. She climbed and clambered all over the cabin, on the roof, along the eaves, and in the dark dry crawl space below reachable only through the trap door in the woodshed. She took notes in a notebook and photographs with her cell phone, and she interviewed her mom and dad and Dave, and conducted a population survey of the beings in the house—animal and vegetable—from insects (Arthropoda) to mosses (Bryophyta) to Dad (Paternosotra, said her father), and finally she set to work. First she drew a map to the scale of one foot of house equaling one inch of map, in which she recorded every being’s movement in or on or through the house for one hour on a Saturday morning. Then she drew a second map, noting every being’s lowest and highest physical presence for the same hour; Dave, for example, went from sprawled on the floor by the fireplace to standing on the roof staring at the sky in which he was sure for a moment that he had heard sandhill cranes. Then she drew a third map, noting the places in the house where the most paths crossed the most times during that hour; she labeled these Crossroads and colored them in green. Then she drew a fourth map, noting the places where not a single being had been during the course of the hour; she labeled these The Arid Lands and colored them in red. Then she drew a fifth map, in which she redesigned the cabin so that all the Crossroads were in the same room and all The Arid Lands were in a closet. Then she added a sonic map, showing, in different color inks, the musical tones of all utterances and voicings in the house over the course of the same hour. To this she added a recording of each tone, captured on a thumb drive. Finally, she wrote a two-page essay called “A Poem Without Any Words” about all the places in the house that she loved because beings she loved were somehow connected in the most subtle and gentle ways to those places—the place on the wall next to the thermostat where her dad leaned his right hand as he used his left to turn the heat down at night, so that after years of turning down the heat there was a gentle vertical poem on the wall written by thousands of nights of turning down the heat; and the tiny poem on the headboard of her bed in the bear’s den where the finch rubbed its beak every evening before going to sleep; and the infinitesimal penciled poem on the frame of the porch door where Dave had written his rising elevation over the years; and the gentle sag in the couch like a cupped leather palm where her mother had fallen asleep curled like a cat every third night or so for years; and the tiny nick in the kitchen wall that was the poem of the frying pan kissing the wall when you hung it up after cleaning it and it swung and tinked the wall once before coming to rest; and many other things, too many to list here, for eventually paragraphs have to end, even the most warm and lovely and riveting ones, like this.

THE UNABLED LADY LIVED ALONE,

for complicated reasons having to do with money and love and loss, but another woman came every morning to help. This was Mrs. Simmons, who was about the same age but had a body that moved more freely than the Unabled Lady’s body did, so Mrs. Simmons did the laundry and cooked a bit and cleaned the bathroom and windows and did things around the house that needed to be done. She was not a nurse, quite, although she was a competent and gentle assistant in moments of medical and physical stress. She was not a caretaker, either, quite, as her service to the Unabled Lady was recompensed partly with money but also with vegetables from the garden and a share of the gifts that occasionally came the Unabled Lady’s way through the largesse of the community, such as elk tenderloins and deer burger and the occasional huckleberry milk shake, and rides to the city and homemade ale and pears and cherries from the vast orchards to the north and east of the mountain, and books from the library’s overflow sale, and one time an American flag with only forty-eight stars, which the Unabled Lady and Mrs. Simmons traded back and forth every few months just for fun, taking turns hanging it proudly in awed celebration of and gratitude for—as the Unabled Lady liked to say—Mr. Thomas Jefferson’s skills with the first draft and Mr. Benjamin Franklin’s skills as an editor thereafter.

Mrs. Simmons came every day but usually only for a couple of hours, as she had three other housecleaning jobs per week, and it should be said here, before we go any further in this sentence, that she did superb work. She never rested at all but filled her two hours thoroughly; as she often said, there were always more things to be done than you could possibly do, and sitting even for a moment allowed old weary in. You best keep in motion, as she said, so as old weary cannot get a toehold. Old weary is a slippery thing. It is the most amazingly patient of things. It will get you in the end, anyways, but if you keep in motion, old weary cannot get footing. One thing I have learned in life is just that. Old weary will take you in his arms eventually, but you got to dance and fence with old weary until then. O yes. Old weary is so polite and gentle. He is so warm and friendly that you want to just lie down and say alright, old weary, you have your way with me; I am ready for you. But when you do that you will be dead, and when you are dead you just can

not

get your work done, and that is a fact.