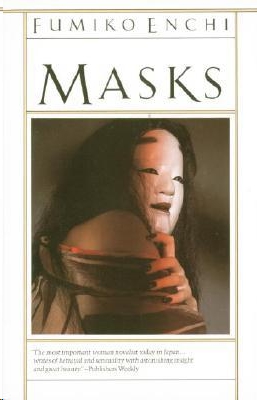

Masks

Authors: Fumiko Enchi

Vintage Edition, October 1983

Copyright © 1958, 1983 by Fumiko Enchi.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

Originally published in Japan as

Onna-men

by Kodansha, Ltd., Tokyo. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. in 1983.

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Enchi, Fumiko, 1905-

Masks.

I. Title.

PL826.N30513 1983b 895.6’35 83-6655

ISBN 0-394-72218-3 (pbk.)

eBook ISBN 9781101970638

v4.1

a

YŌ NO

O

NNA

Tsuneo Ibuki and Toyoki Mikamé sat facing one another in a booth in a coffee shop on the second floor of Kyoto Station.

Between them on the narrow imitation-wood tabletop were a vase holding a single white chrysanthemum and an ashtray piled high with cigarette butts, suggesting that the two men had been in conversation for some time. Both had been in western Japan on business during the past several days and they had met by chance when Mikamé stepped inside the coffee shop earlier. Friends since college days, they had greeted one another with the throaty grunts that passed for hellos between them; then Mikamé had dropped down heavily across from Ibuki, who was seated alone, drinking a cup of coffee.

“When did you get here?” Ibuki asked quietly, his words accompanied by a nervous blink. Beneath the corners of his eyes the cheekbones stood out sharply; his cheeks were gaunt and hollow. An aquiline nose saved his face from being unrefined, and his bony, large-knuckled fingers were elegantly long and thin.

Ibuki’s familiar mild voice, his cigarette balanced just so between two slender fingertips oppressed Mikamé in a way that, as usual, he found curiously agreeable—like being confronted by a woman who was at once both cruel and beautiful.

“There was a medical conference in Osaka. I left Tokyo on the second. What about you?”

“I’ve been here a week, doing a lecture series for S. University. Just finished yesterday. I’m staying here at the station hotel.”

“Are you? I couldn’t have run into you at a better time. I have a ticket back to Tokyo on the train tonight. I stopped in Kyoto for the fun of it, then couldn’t decide what to do next.”

“Good timing,” said Ibuki. “Right now I’m waiting for somebody. She should be here at two. Somebody you know.”

“Who?”

“Mieko Toganō.”

“She’s in Kyoto too?”

“Yes, Kōetsu Temple put up a stone engraving of a poem by Junryo Kawabé, and she came for the unveiling.”

“Kawabé…is she one of his circle?”

“Oh, yes; they both belong to the

Clear Stream

school of poetry, you know.” Ibuki looked away and slowly flicked an ash from the end of his cigarette. “Yasuko is with her.”

“Oh?” Mikamé was impassive. “Where are they staying?”

Yasuko was the widow of Mieko Toganō’s late son, Akio. Their marriage had lasted barely a year before Akio was killed suddenly in an avalanche on Mount Fuji. After the funeral, Yasuko had not gone back to her parents but had remained in the Toganō family, helping her mother-in-law edit a poetry magazine and auditing Ibuki’s classes in

Japanese literature at the university where he was assistant professor. She was also involved in a detailed study of spirit possession in the Heian era, a continuation of research that Akio had left unfinished. Ibuki and others supposed she had chosen this as a way of staying close to her husband’s memory.

Ibuki had been Akio’s senior in the department by several years and had known him fairly well, both men being specialists in Heian literature; his acquaintance with Yasuko and Mieko, on the other hand, had not developed until after Akio’s death, when he had been called on to advise Yasuko in her research. Mikamé was also engaged in the study of spirit possession, although his approach was rather different. Holder of a doctorate in psychology, he was in addition an amateur of folklore studies. Having studied devil possession in postbiblical Europe and the Near East, he had gone on to publish several historical surveys of Japanese folk beliefs, including belief in possession by fox spirits along the coast of the Japan Sea, by dog spirits in Shikoku, and by snake spirits in Kyushu. Of late, he too had taken an interest in the possessive spirits that cropped up in Heian literature (malign phantoms of the living or dead that forcibly took possession of others), and through Ibuki he had come to know Mieko and Yasuko. Together with some others whose interests were similar, they had formed a discussion group which met every month or two at the Toganō home.

The group tended naturally to revolve around Yasuko, but behind Yasuko was always Mieko Toganō, lending to the gatherings by her mere presence an old-fashioned easiness and grace. Yasuko was at all times charming, sparkling with intelligence as well as beauty, yet to Ibuki it was clear that her vitality depended absolutely on the serene composure of Mieko’s silent, seated figure.

In any case, Mikamé seemed highly pleased to hear that Yasuko and Mieko were also in Kyoto.

“They’re at the Camellia House on Fuya Street,” said Ibuki. “This afternoon Mieko is going to call on Yorihito Yakushiji, the Nō master. He’s showing some of his old masks and costumes, and she’s invited me along.”

“Really? How long has she known him?”

“It seems his daughter is one of her pupils. Their storehouse is open for its fall airing, and I’ve heard that some of the costumes are three hundred years old or more. Don’t you want to come?”

“Well, old masks and costumes aren’t exactly what I had in mind for today, but then again I would like to see Mieko and Yasuko. I had thought when I came in here, I’d just stop for a minute and then maybe go look up a friend of mine in the medical school, but I think I will join you, if you’re sure no one will mind.”

“I wouldn’t worry. Anyway, why don’t you at least sit back and wait for Yasuko? She won’t be along for at least a half hour.”

“Half an hour! What are you doing here so early?”

Ibuki was silent. Instead of a reply, he said, “The last time we saw each other was at that séance, remember?”

“Oh, yes, the séance. That was right around the middle of last month, wasn’t it?”

“The seventeenth. Yasuko mentioned it was the same as the day Akio died, so it stuck in my mind.”

“Peculiar business, that séance…If that spiritualist had something up his sleeve, he certainly kept it hidden.”

“Saeki had himself a field day, didn’t he?”

The man of whom Ibuki spoke was both a professor of applied science and a believer in the power of the Lotus Sutra. Convinced that the day was near when science and religion would at last be reconciled, he was a great devotee

of spiritualism and had arranged for a séance to be held in his office. Mieko had not attended, but Yasuko, Ibuki, and Mikamé were among the participants.

The medium was a woman of about thirty, dressed in a black mixed-weave suit. She was said to have grown up in Manchuria and had a countrified air and a sturdy, rawboned physique. Her expression contained none of the shadows one expected in a woman of psychic gifts. Her speech was slow, as if somehow her tongue were the wrong size for her mouth. The spiritualist, a spare and thin-lipped man, seated her beside him in the center of the room, and then began by explaining to the twenty or so people assembled about communication between this world and the next. Spirits that depart this life, he told them, float ceaselessly through the atmosphere, walking alongside the living and sharing the space around them, even though their bodies cannot be seen, nor their voices heard. Long ago the ability to hear and speak with spirits had been widespread, but with the rise of industrial civilization it had grown progressively rarer. The woman who would serve as medium that day was one of a select few who still possessed the gift of communicating with the dead.

“Now, in order to convince you that what you are about to see is genuine, I will tie the medium to this chair before your eyes. Watch carefully, please, to see what happens around her in the dark.” The eyes behind his glasses never blinked. Displaying the knot in the cord binding the medium’s hands, the spiritualist then placed a large metal screen around her.

When the room lights were off, a megaphone, pencils, notebooks, and other miscellaneous objects painted with luminous paint glowed white in the darkness. Strains of “The Blue Danube” emerged softly from a phonograph.

Ibuki and Mikamé sat on either side of Yasuko, their eyes transfixed on the spot where the medium sat bound. Ibuki found himself distracted by a disquieting awareness of Yasuko’s supple neck and softly rounded arm as she sat with her right shoulder slightly lowered, pressing close against him. Doubtless she was peering into the dark, watching carefully to see what might happen. He knew that were it not dark she would have been taking notes for Mieko, and since that was impossible she was no doubt tense with the effort to remember everything accurately. Time and again he was assailed by an impulse to put his arm around her and gently draw her small head closer. It was as if the customary restraints on his physical desire had begun to fall away and disappear, rendered insubstantial by the eerie mood of the séance.

Then in the darkness came a noise like that of knuckles sharply striking a tabletop. “Ah!” said the spiritualist. “The rapping has begun.”

After a time a line of white—too frail to seem to be a ray of light—made a brief pale arc in the blackness. Simultaneously the megaphone on the table flew high in the air, as if someone had given it a toss.

The medium had evidently begun to shake; they heard her chair clattering against the floor. At every occurrence of the rapping sound the white line reappeared, and notebooks or pencils slid off the table as if blown by a stiff wind. Incoherent sounds, like groans or prayers, began issuing from the medium’s lips.

The spiritualist stopped the record and stood up. “Contact has been made; let us begin the questioning. Hello—who are you?”

From the mouth of the medium came a deep male voice, as if somewhere a switch had been thrown.

“Je suis descendu de la montagne, je m’en vais à la montagne.”

“What? What language is that?”

“That’s French,” volunteered a voice from among the listeners. “It means ‘I came from the mountain, I go to the mountain.’ ”

“There—did everyone hear that? It must be the spirit of a Frenchman. An Alpinist, perhaps.”

“I came from the mountain…I go to the mountain…” Yasuko echoed the words in an empty voice that was half a sigh, then moved her hand out in search of Ibuki’s and touched his knee. He responded by grasping her hand tightly in both of his, so enthralled by the husky male voice coming from the medium’s throat that he failed to register the strangeness in Yasuko’s quick, spontaneous gesture.

In the darkness, a student who spoke fluent French conducted a colloquy with the medium, and then reported that the spirit was that of a mountaineer who had fallen into a crevasse and died on the Matterhorn.

“Do you know where this is?”

“No,” replied the medium. “This is a dimly lighted place, dry and full of dust.”

“When did you die?”

“Nineteen twelve.”

“Do you know how much time has gone by since then?”

“No. I am walking somewhere where there is ice, and snow, and darkness, and a sharp wind…it could be five thousand meters above sea level or more.”

“Did you have a wife and children?”

“A wife, yes. I don’t recall children.”

“No children?”

“I don’t think so.”

“Just now there was a rapping sound, and then notebooks fell on the floor and the megaphone flew up in the air. Was it you who caused those objects to move?”

“I didn’t move them. They were in my way, so they moved aside by themselves.”

“What is your name?”

“Jean Matois.”

“And how old were you when you died?”

“Stop badgering me! I’ve forgotten…” The medium said this last in a tone of exasperation.

“The spirit has left. It took offense,” said the spiritualist, switching on the lights. Beneath the screen the medium sat with her face upturned, still tightly bound to the chair, looking as limp and exhausted as if she had undergone torture. Her eyes were screwed shut, her mouth opened and closed convulsively like a fish, and her arms and legs shook spasmodically, as if filled with electricity. The room was in such disarray that it might have been hit by a tornado: chairs lay overturned; a tall corner stand had tipped over sideways; along with the megaphone, notebooks, and pencils, countless sheets of notepaper were strewn across the floor.

“That paper had something to do with it,” said Mikamé recalling that afternoon. “If he

did

have something up his sleeve. At the time I felt inclined to believe him, but a week later a friend of mine took me to a nightclub where I saw a very talented magician. This man would take a lighted cigarette and stick it in his ear, say, and then pull it out from somewhere else. It was impossible to tell how. That made me think. With parlor tricks, the audience knows all along they’re being fooled, no matter how convincing the act may look—right? And at that séance I had my doubts from the start. I suppose I didn’t really want it to be genuine. A skilled magician would have no trouble taking advantage of a setup like that. Every one of those effects could have been done by simple conjuring.”

“Even the French?” said Ibuki. To him, more mysterious

than the séance itself had been that moment when the lights came on to reveal Yasuko’s hand resting in his. He also had a vivid recollection of an uncomfortable moment when Mikamé’s eyes had seemed to focus sharply on their clasped hands. Today he had made sure to bring up the séance, mainly out of a desire to test whether his memory was correct, but perhaps, after all, Mikamé had been too absorbed in the other goings-on that day to notice what was happening beside him. “That student told me later that the voice spoke French with a strong southern accent. His father is a foreign diplomat, and he grew up in France himself, so he certainly ought to know. It would surprise me somehow if that woman could speak French on her own.”

“Maybe not consciously. But it’s at least conceivable that she has the ability to pick up the voices of real human beings from around the world, like a radio picking up air waves. To me that makes far more sense than the idea that the spirit of some dead person was talking to us through her.”

“So it was the spirit of a living person, you think—a living ghost?”

“Call it what you want. It’s not the spirit that interests me; it’s the words the woman used—real words, spoken somewhere by a real human being. That and the voice—the way she could tune in on it and re-create it so well. All the talk beforehand about souls of the dead and voices from the beyond made it eerie, but when you come down to it, that could just as well have been some fur trader in the Alps, talking in a bar in a small town somewhere in the south of France. I wrote it all down afterward, and when you take those words apart and look at them, they could just as well be part of a conversation about somebody else who died.”