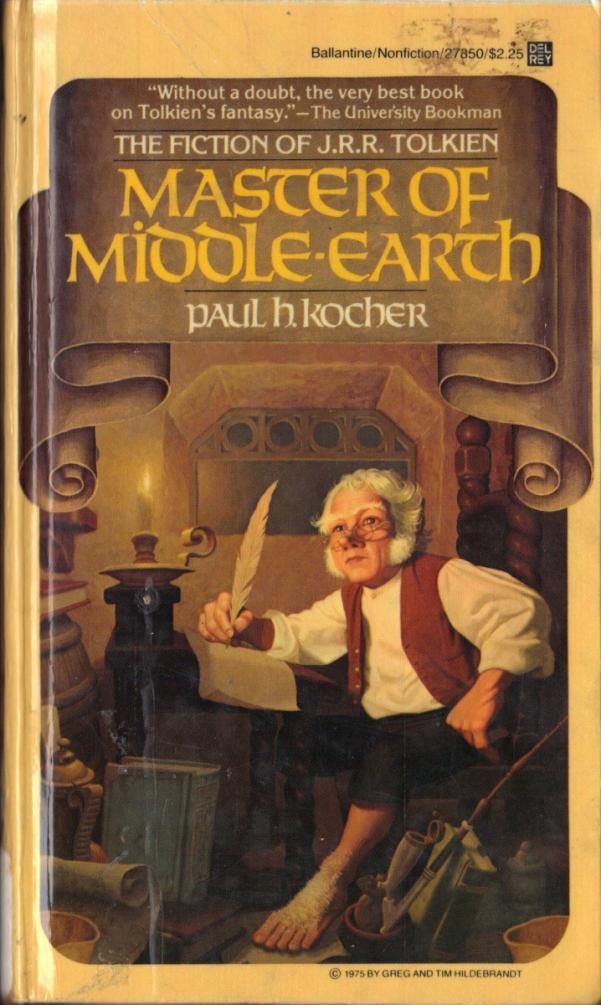

Master of Middle Earth

Read Master of Middle Earth Online

Authors: Paul H. Kocher

Master of Middle-Earth

The

Fiction of J. R. R. Tolkien

Paul H. Kocher

In

1938 when Tolkien was starting to

write

The Lord of the Rings

he also delivered a lecture at the

University of St. Andrews in which he offered his views on the types of world

that it is the office of fantasy, including his own epic, to

"sub-create," as he calls it. Unlike our primary world of daily fact,

fantasy's "secondary worlds" of the imagination must possess, he

said, not only "internal consistency" but also "strangeness and

wonder" arising from their "freedom from the domination of observed

fact."

1

If this were all, the secondary world of faery would

often be connected only very tenuously with the primary world. But Tolkien

knew, none better, that no audience can long feel sympathy or interest for

persons or things in which they cannot recognize a good deal of themselves and

the world of their everyday experience. He therefore added that a secondary

world must be "credible, commanding Secondary Belief." And he

manifestly expected that secondary worlds would combine the ordinary with the

extraordinary, the fictitious with the actual:

"Faerie

contains

many things besides elves and fays, and besides dwarfs, witches, trolls, giants

or dragons: it holds the seas, the sun, the moon, the sky; and the earth and

all things that are in it: tree and bird, water and stone, wine and bread, and

ourselves, mortal men, when we are enchanted."

Tolkien followed

his own prescription in composing

The Lord of the Rings,

or perhaps he

formulated the prescription to justify what he was already intending to write.

In either case the answer to the question posed by the title of this chapter is

"Yes, but—." Yes, Middle-earth is a place of many marvels. But they are

all carefully fitted into a framework of climate and geography, familiar skies

by night, familiar shrubs and trees, beasts and birds on earth by day, men and

manlike creatures with societies not too different from our own. Consequently

the reader walks through any Middle-earth landscape with a security of

recognition that woos him on to believe in everything that happens. Familiar

but not too familiar, strange but not too strange. This is the master rubric

that Tolkien bears always in mind when inventing the world of his epic. In

applying the formula in just the right proportions in the right situations

consists much of his preeminence as a writer of fantasy.

Fundamental to

Tolkien's method in

The Lord of the Rings

is a standard literary pose

which he assumes in the Prologue and never thereafter relinquishes even in the

Appendices: that he did not himself invent the subject matter of the epic but

is only a modern scholar who is compiling, editing, and eventually translating

copies of very ancient records of Middle-earth which have come into his hands,

he does not say how. To make this claim sound plausible he constructs an

elaborate family tree for these records, tracing some back to personal

narratives by the four hobbit heroes of the War of the Ring, others to

manuscripts found in libraries at Rivendell and Minas Tirith, still others to

oral tradition.

2

Then, in order to help give an air of credibility

to his account of the War, Tolkien endorses it as true and calls it history,

that is, an authentic narrative of events as they actually happened in the

Third Age. This accolade of history and historical records he bestows

frequently in both Prologue and Appendices. With the Shire Calendar in the year

1601 of the Third Age, states the Prologue," . . . legend among the

Hob-bits first becomes history with a reckoning of years." A few pages

farther on, Bilbo's 111th birthday is said to have occurred in Shire year 1041:

"At this point this History begins." And in Appendix F Tolkien

declares editorially, "The language represented in this history by English

was the

Westron

or 'Common Speech' of the West-lands of Middle-earth in

the Third Age."

3

Many writers of

fantasy would have stopped at this point. But Tolkien has a constitutional

aversion to leaving Middle-earth afloat too insubstantially in empty time and

place, or perhaps his literary instincts warn him that it needs a local

habitation and a name. Consequently he takes the further crucial step of

identifying it as our own green and solid Earth at some quite remote epoch in

the past. He is able to accomplish this end most handily in the Prologue and

Appendices, where he can sometimes step out of the role of mere editor and

translator into the broader character of commentator on the peoples and events

in the manuscripts he is handling. And he does it usually by comparing

conditions in the Third Age with what they have since become in our present.

About the hobbits,

for instance, the Prologue informs the reader that they are "relations of

ours," closer than elves or dwarves, though the exact nature of this blood

kinship is lost in the mists of time. We and they have somehow become

"estranged" since the Third Age, and they have dwindled in physical

size since then. Most striking, however, is the news that "those days, the

Third Age of Middle-earth, are now long past, and the shape of all lands has

been changed; but the regions in which Hobbits then lived were doubtless the

same as those in which they still linger: the Northwest of the Old World, east

of the Sea."

There is much to

digest here. The Middle-earth on which the hobbits lived is our Earth as it was

long ago. Moreover, they are still here, and though they hide from us in their

silent way, some of us have sometimes seen them and passed them on under other

names into our folklore. Furthermore, the hobbits still live in the region they

call the Shire, which turns out to be "the North-West of the Old World,

east of the Sea." This description can only mean northwestern Europe,

however much changed in topography by eons of wind and wave.

Of course, the

maps of Europe in the Third Age drawn by Tolkien to illustrate his epic show a

continent very different from that of today in its coastline, mountains,

rivers, and other major geographical features. In explanation he points to the

forces of erosion, which wear down mountains, and to advances and recessions of

the sea that have inundated some lands and uncovered others. Singing of his

ancestor Durin, Gimli voices dwarf tradition of a time when the earth was newly

formed and fair, "the mountains tall" as yet unweathered, and the

face of the moon as yet unstained by marks now visible on it. Gandalf objects

to casting the One Ring into the ocean because "there are many things in

the deep waters; and seas and lands may change." Treebeard can remember

his youth when he wandered over the countries of Tasarinan, Ossiriand,

Neldoreth, and Dorthonion, "And now all those lands he under the

wave." At their parting Galadriel guesses at some far distant future when

"the lands that he under the wave are lifted up again" and she and

Treebeard may meet once more on the meadows of Tasarinan. Bombadil recalls a

distant past, "before the seas were bent." By many such references

Tolkien achieves for Middle-earth long perspectives backward and forward in

geological time.

One episode in

particular, the reign of Morgoth from his stronghold of Thangorodrim somewhere

north of the Shire for the three thousand years of the First Age, produces

great changes in Middle-earth geography. To bring about his over-throw the

Guardian Valar release titanic natural forces, which cause the ocean to drown

not only his fortress but a vast area around it, including the elf kingdoms of

Beleriand, Nargothrond, Gondolin, Nogrod, and Belagost. Of that stretch of the

northwestern coast only Lindon remains above the waves to appear on Tolkien's

Third Age maps. The flooding of rebellious Númenor by the One at the end of the

Second Age is a catastrophe of equal magnitude.

But Tolkien gives

the realm of Morgoth an extra level of allusiveness by describing it as so

bitterly cold that after its destruction "those colds linger still in that

region, though they lie hardly more than a hundred leagues north of the

Shire." He goes on to describe the Forod-waith people living there as

"Men of far-off days," who have snow houses, like igloos, and sleds

and skis much like those of Eskimos. Add the fact that the Witch-king of Angmar

(thereafter called simply Angmar), Morgoth's henchman, has powers that wane in

summer and wax in winter and it becomes hard not to associate Morgoth in some

way with a glacial epoch, as various commentators have already done. In his

essay "On Fairy-stories" Tolkien refuses to interpret the Norse god

Thorr as a mere personification of thunder.

4

Along the same lines,

it is not his intention, I think, to portray Morgoth as a personification of an

Ice Age. However, it would seem compatible with his meaning to consider Morgoth

a spirit of evil whose powers have engendered the frozen destructiveness of

such an age.

The possibility

thus raised of fixing the three Ages of Middle-earth in some interglacial lull

in the Pleistocene is tempting, and may be legitimate, provided that we do not

start looking about for exact data to establish precise chronologies.

5

The data are not there, and Tolkien has no intention whatever of supplying

them. The art of fantasy flourishes on reticence. To the question how far in

Earth's past the Ages of Middle-earth lie, Tolkien gives essentially the

storyteller's answer: Once upon a time—and never ask what time. Choose some

interglacial period if you must, he seems to say, but do not expect me to bind

myself by an admission that you are right. Better for you not to be too sure.

Tolkien's

technique of purposeful ambivalence is well shown too in the Mumak of Harad,

which Sam sees fighting on the side of the Southrons against Faramir's men in

Ithilien: ". . . indeed a beast of vast bulk, and the like of him does not

now walk in Middle-earth; his kin that live still in the latter days are but

memories of his girth and majesty." As compared with its "kin,"

the elephant of today, the ancestral Mumak was far more massive.

8

Is

Tolkien hinting that it is a mammoth? Perhaps, but it is not shaggy, it is

coming up from the warm south, and it is totally unknown to the hobbits farther

north, where that sort of creature might be expected to abound. Tolkien is

equally evasive about Angmar's huge winged steed, featherless and leathery:

"A creature of an older world maybe it was, whose kind, lingering in

forgotten mountains cold beneath the Moon, outstayed their day ..." A

pterodactyl? It certainly sounds like one, but Tolkien avoids naming it, and

casts all in doubt with a maybe. If it is a pterodactyl, or a close relative,

then the Age of Reptiles in which those species throve is "older"

than the Third Age, apparently much older. Gwaihir is an eagle of prodigious

size whose ancestor "built his eyries in the inaccessible peaks of the

Encircling Mountains when Middle-earth was young." All these half-mythical

creatures of Middle-earth are meant to subsist partly in our world, partly in

another in which the imagination can make of them what it will.

Tolkien's lifelong

interest in astronomy tempts him into observations which have a bearing on the

distance of Middle-earth back in Earth's prehistory. Opening in Appendix D a

discussion of the calendars devised by its various peoples he remarks,

"The Calendar in the Shire differed in several features from ours. The

year no doubt was of the same length, for long ago as those times are now

reckoned in years and lives of men, they were not very remote according to the

memory of the Earth." A footnote on the same page gives "365 days, 5

hours, 8 minutes, 46 seconds" as the period of Earth's annual revolution

around the sun according to our best modern measurements. The year length for

Middle-earth of the Third Age was the same, Tolkien says. In other words,

Earth's orbit around the sun (or vice versa) was the same then as it is now.

This bit of information is not as informative as it looks. In the absence of

modern technology nobody before today could possibly have calculated the orbit

with sufficient accuracy to tell at what epoch.it began being different. But

the implication is that at least the Third Age was not many millions of years

ago. Tolkien wants for Middle-earth distance, not invisibility.

To strengthen

visibility, and also to counterbalance the alien topography of Middle-earth's

Europe, Tolkien lights its night skies with the planets and constellations we

know, however different their names. Orion is seen by hobbits and elves meeting

in the Shire woods: ". . . there leaned up, as he climbed over the rim of

the world, the Swordsman of the Sky, Menelvagor with his shining belt."

Unmistakably Orion. Looking out the window of the inn at Bree, "Frodo saw

that the night was clear. The Sickle was swinging bright above the shoulders of

Bree-hill." Tolkien takes the trouble to add a footnote on that page- that

"the Sickle" is "the Hobbits' name for the Plough or Great

Bear." Glowing like a jewel of fire "Red Borgil" would seem to

be Mars. Eärendil's star is surely Venus, because Bilbo describes it as shining

just after the setting sun ("behind the Sun and light of Moon") and

just before the rising sun ("a distant flame before the Sim,/a wonder ere

the waking dawn ...").