Mastering the Art of French Cooking, Volume 2 (25 page)

Read Mastering the Art of French Cooking, Volume 2 Online

Authors: Julia Child

We have had the great good fortune of being able to work with Professor R. Calvel, of the École Professionelle de Meunerie, a trade school established in Paris to teach the profession of milling and baking to students and bakers from all over France. The science of bread making and the teaching of its art are the life work of Professor Calvel, and thanks to his enthusiastic help, which set us on the right track, we think we have developed as professional a system for the home baker as anyone could hope for. You will be amazed at how very different the process is from anything you have done before, from the mixing and rising to the very special method of forming the dough into loaves.

FLOUR

French bakers make plain French bread out of unbleached flour that has a gluten strength of 8 to 9 per cent. Most American all-purpose flour is bleached and has a slightly higher gluten content as well as being slightly finer in texture. It is easier to make bread with French flour than with American all-purpose flour, and the taste and texture of the bread are naturally more authentic. (The so-called bread flour available in some mail-order houses usually has an even higher gluten content than all-purpose flour, so do not use it for plain French bread.) You will undoubtedly wish to experiment with flours if you become a serious bread maker, but because we find that any of the familiar brands of all-purpose flour works very well, we shall not complicate the recipe by suggesting an obscure or special brand. If you do experiment, however, simply substitute your other

flour for the amount called for in the recipe; you may need a little bit more water or a little bit less, but the other ingredients and the method will not change.

BAKERS’ OVENS VERSUS HOME OVENS

Bakers’ ovens are so constructed that one slides the formed bread dough from a wooden paddle right onto the hot, fire-brick oven floor, and a steam-injection system humidifies the oven for the first few minutes of baking. Steam allows the yeast to work a little longer in the dough and this, combined with a

hot baking surface, produces an extra push of volume. In addition, steam coagulating the starch on the surface of the dough gives the crust its characteristic brown color. Although you can produce a good loaf of French bread without steam or a hot baking surface, you will get a larger and handsomer loaf when you simulate professional conditions. We give both systems—the Master Recipe, which requires no special equipment, and the

simulated baker’s oven system

.

SOUR DOUGH

Sour dough is an American invention, not French, and you will not find anything like American sour dough in France. But you can adapt your sour dough recipe to the method described here for plain French bread. We think you will find that our recipe will give you an excellent result.

EQUIPMENT NEEDED FOR MAKING FRENCH BREAD

Unless you plan to go into the more elaborate simulation of a baker’s oven, you need no unusual equipment for the following recipe. Here are the requirements, some of which may sound odd but will explain themselves when you read the recipe.

A 4- to 5-quart mixing bowl with fairly vertical rather than outward-slanting sides

A kneading surface of some sort, 1½ to 2 square feet

A rubber spatula and either a metal scraper or a stiff wide metal spatula

1 or 2 unwrinkled canvas pastry cloths or stiff linen towels upon which the dough may rise

A stiff piece of cardboard or plywood 18 to 20 inches long and 6 to 8 inches wide, for unmolding dough from canvas to baking sheet

Finely ground cornmeal, or pasta pulverized in an electric blender, to sprinkle on unmolding board so as to prevent dough from sticking

The largest baking sheet that will fit into your oven

A razor blade for slashing the top of the dough

A soft pastry brush or fine-spray atomizer for moistening dough before and during baking

A room thermometer to verify rising-temperature

PAIN FRANÇAIS

[Plain French Bread]

Count on a minimum of 6½ to 7 hours from the time you start the dough to the time it is ready for the oven, and half an hour for baking. While you

cannot take less time, you may take as much more time as you wish by using the delayed-action techniques described at the end of the recipe.

For 1 pound of flour

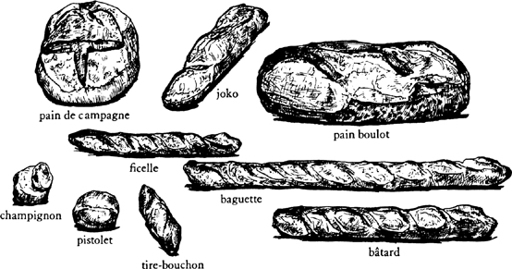

, making 3 cups of dough, producing:

3 long loaves,

baguettes

, 24 by 2 inches, or

bâtards

, 16 by 3 inches

Or 6 short loaves,

ficelles

, 12 to 16 by 2 inches

Or 3 round loaves,

boules

, 7 to 8 inches in diameter

Or 12 round or oval rolls,

petits pains

Or 1 large round or oval loaf,

pain de ménage

or

miche; pain boulot

1)

The dough mixture—le fraisage

(

or frasage

)

NOTE

: List of equipment needed is in paragraph preceding this recipe.

1 cake (0.6 ounce) fresh yeast or 1 package dry-active yeast

⅓ cup warm water (not over 100 degrees) in a measure

3½ cups (about 1 lb.) all-purpose flour, measured by scooping dry-measure cups into flour and sweeping off excess

2¼ tsp salt

1¼ cups tepid water (70 to 74 degrees)

Stir the yeast in the warm water and let liquefy completely while measuring flour into mixing bowl. When yeast has liquefied, pour it into the flour along with the salt and the rest of the water.

NOTE

: We do not find the food processor satisfactory here, since the dough is so soft the machine clogs; however, you can use a heavy-duty mixer with dough hook, and

finish it up by hand

.

Stir and cut the liquids into the flour with a rubber spatula, pressing firmly to form a dough, and making sure that all bits of flour and unmassed pieces are gathered in. |

|