Masters of Death (11 page)

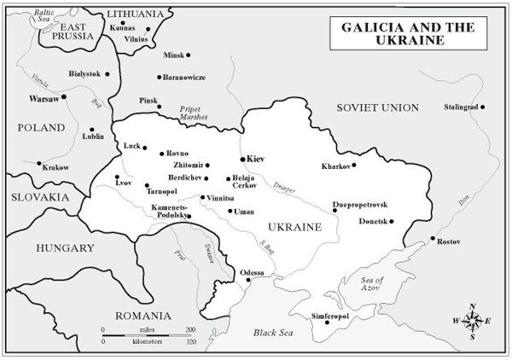

The rolling, temperate grasslands of the western Ukraine resemble the American prairies: black or red gypsum soils; limestone bluffs penetrated with caves; crops of wheat, rye and barley, soybeans, sunflowers; orchards in the uplands. Luck (Lutsk), eighty miles east of Lublin, marks the southern edge of the vast Pripet marshes of southern Byelorussia and the northern Ukraine that extend eastward from Lublin along the drainage of the Pripet River all the way to the Pripet’s junction with the Dnieper above Kiev. One hundred twenty miles southeast of Lublin, Lvov (Lemberg), the old capital of Galicia in the foothills of the Carpathian Mountains, thrived on the historic trade route between Vienna and Kiev; its 1941 population of 370,000 included 160,000 Jews, 140,000 Poles and 70,000 Ukrainians. Eighty miles due east of Lvov on the south-flowing Seret River, Tarnopol counted 40,000 residents, including 18,000 Jews. Twenty miles farther down the Seret from Tarnopol, the small town of Trembowla, population 10,000, including 1,800 Jews, paralleled the river below an old castle ruin.

A young man in Trembowla, listening to Radio Berlin on a friend’s shortwave radio on 22 June 1941, heard an important member of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN) demand “ ‘Death to Jews, death to Communists, death to Commissars,’ exactly in that sequence.” Thousands of young Ukrainian nationalists had defected to Nazi-occupied Poland after September 1939. Himmler had formed them into two Waffen-SS battalions, Nachtigal and Roland, which would return to plague Lvov and Tarnopol.

An advance unit of Einsatzgruppe C entered Luck on 27 June 1941 while the town was still burning. “Everything was still in wild confusion,” the unit would report. “All shops had been looted by the population.” In the courtyard of the fourteenth-century castle in the center of town the invaders found the piled bodies of more than a thousand Ukrainians whom the NKVD had murdered before withdrawing—all they had time to kill of the four thousand prisoners stuffed within the massive castle walls. Several days later, perhaps among the castle dead, the Wehrmacht discovered ten German soldiers the NKVD had murdered. Field Marshal Walther von Reichenau, the commander of the Sixth Army that was fighting through the area, ordered an execution of Jews equal in number to the Ukrainian dead.

By then the Einsatzgruppe had already arrested and shot several hundred Jewish citizens and a handful of looters. All of its commandos had briefly come together in Luck at the same time before fanning out across the Ukraine, among them Sonderkommando 4a, which Paul Blobel commanded. Apparently the responsibility for carrying out von Reichenau’s order fell to Sonderkommando 4a and came just when Blobel was succumbing to typhoid fever. A rangy man with red hair, a beak of a nose, a cleft chin and a permanent scowl, no stranger to violence, Blobel was a veteran of the First World War and had even won the Iron Cross, 1st Class, but fever and the execution order combined to produce what he later called “a nervous breakdown.” His subordinate, SS-OBERSTURMFÜHRER August Häfner, returned from a journey to find “my unit . . . all running around like lost sheep. I realized something must have happened and asked what was wrong.” Someone told Häfner that Blobel had collapsed and was in bed in his room:

I went to the room. Blobel was there. He was talking confusedly. He was saying that it was not possible to shoot so many Jews and that what was needed was a plow to plow them into the ground. He had completely lost his mind. He was threatening to shoot Wehrmacht officers with his pistol. It was clear to me that he had cracked up and I asked [fellow Obersturmführer] Janssen what had happened. Janssen told me that Reichenau had issued an order. . . . No preparations to carry out this order had yet been made. . . . I had someone call a doctor. . . . When the doctor saw the condition Blobel was in he gave him an injection and instructed us to have him taken to Lublin to a hospital. While he was being examined Blobel kept on reaching for his pistol. By talking to him I managed to calm him down enough so that he did not fire.

Another officer with Sonderkommando 4a, Russian-speaking Sturmbannführer Waldemar von Radetzky, takes up the story:

Blobel had a high temperature and was delirious. The physician was most upset about the state of health of his colleague. He made out an admission card for the field hospital in Lublin, and he treated Blobel. Blobel was taken in his car, and I went to Lublin with him the same evening, where we arrived in the morning and took him to the hospital there.

Häfner, a solid, square-jawed young officer, also accompanied Blobel to Lublin in the Opel Admiral. He remembered that they delivered their chief “to a hospital which was known as a loony bin by the enlisted men.” Blobel was put in quarantine and spent the whole month of July recuperating, rejoining SK 4a at the beginning of August. His two subordinates returned to Luck the next day to find that Himmler’s newly appointed Higher SS and Police Leader for the Ukraine, the coldly murderous forty-six-year-old Obergruppenführer Friedrich Jeckeln, had already arranged for Ukrainian special detachments supervised by platoons of police and infantry to shoot 1,160 Luck Jews in “retaliation.”

Einsatzgruppe staff arrived in Lvov at five a.m. on 1 July 1941 and commandeered the NKVD central building for offices. A week earlier, when the NKVD still controlled Lvov, Ukrainian nationalists had staged an insurrection led by OUN commander Stepan Bandera, who had then proclaimed Ukrainian statehood on 30 June 1941 (a claim the Germans quickly quashed). The NKVD had killed three thousand of the Bandera forces; the Einsatzgruppe would report that “the prisons in Lvov were crammed with the bodies of murdered Ukrainians.” There were earlier NKVD victims buried under the floors of the prison as well.

When the Germans took control of Lvov, a Jewish resident wrote in a contemporary diary, “the devil’s game began”:

The Gestapo decided to make use of what had happened in the prisons under Soviet rule for the purposes of propaganda. In the presence of special commissions, Jews were made to dig out the corpses of the prison inmates. The action was shot by film operators to be shown later as evidence of the execution of innocent people by the “Jewish Bolsheviks.”

. . . The Germans were seizing Jews in the streets or at home and forcing them to work in prison. The arrests of Jews were also conducted by the newly created Ukrainian police. . . . The operation was over in three to four days. Every morning about a thousand Jews were brought and distributed among the three prisons. Some were ordered to break concrete and dig out corpses. Others were shot in the small inner courtyards of the prisons. . . . The “Aryan” residents of Lvov participated in this brutal show. Crowds wandered along prison corridors and courtyards, observing with satisfaction the suffering of the Jews. Here and there volunteers could be found to help the Germans in the beating of Jews. During the first days of the occupation of Lvov more than 3,000 Jews were killed in the Lvov prisons. Among them was one of the best-known and most popular rabbis of Lvov — Dr. Yehezkel Levin and his brother, the rabbi of the town of Zheshkov, Aaron Levin.

Einsatzgruppe C reported a higher number than the diarist: “Approximately 7,000 Jews were rounded up and shot by the Security Police in retaliation for the inhuman atrocities.”

Felix Landau, a sergeant in one of the Einsatzkommandos, kept a diary as well. Landau had volunteered for Einsatzkommando duty when he discovered that his mistress Trude, a typist in the General Government SD office where he worked, was two-timing him with a former fiancé. His unit had pulled into Lvov at four in the afternoon on 2 July 1941 and immediately got busy. “Shortly after our arrival,” he writes, “the first Jews were shot by us. As usual a few of the new officers became megalomaniacs, they really enter into the role wholeheartedly.” After the murders the Einsatzkommando commandeered a military school and forced Jewish prisoners to clean the building before settling down at midnight to sleep. Landau started writing a letter to Trude the next morning “while listening to wildly sensual music” on the radio, but a killing order interrupted his composition: “

EK

with steel helmets, carbines, thirty rounds of ammunition.” Without break the diary resumes: “We have just come back. Five hundred Jews were lined up ready to be shot. Beforehand we paid our respects to the murdered German airmen [casualties of the Barbarossa assault found in Lvov] and Ukrainians.” He had been told at the time his unit “paid [its] respects” that the Bolsheviks had even murdered children, atrocity stories designed to motivate the men to kill. “In the children’s home they were nailed to the walls.” Even so, he told himself, “I have little inclination to shoot defenseless people — even if they are only Jews.”

By 5 July 1941, after a night of guard duty, Landau was looking forward to his first hot meal since the unit arrived in Lvov. Given 10 Reichsmarks to buy necessities, he had bought himself a whip. “The stench of corpses is all-pervasive when you pass the burnt-out houses,” he observes. “We pass the time by sleeping.” That afternoon they “finished off” three hundred more “Jews and Poles.” In the evening he and his buddies went into town. “There we saw things that are almost impossible to describe. We drove past a prison. You could already tell from a few streets away [by the smell] that a lot of killing had taken place here. We wanted to go in and visit it but did not have any gas masks with us so it was impossible to enter the rooms in the cellar or the cells.”

On their way back to the military school they encountered injured Jews passing by who were dusted with sand. “We looked at one another. We were all thinking the same thing. These Jews must have crawled out of the graves where the executed are buried.” They stopped one of the injured men and learned that Ukrainians had rounded up some eight hundred Jewish men and taken them up to the ruins of the High Castle on the hill north of the city. Landau’s Einsatzkommando had been scheduled to shoot them the following day. Instead they were being released, but only after they had run a gauntlet of vengeful Wehrmacht soldiers:

We continued going along the road. There were hundreds of Jews walking along the street with blood pouring down their faces, holes in their heads, their hands broken and their eyes hanging out of their sockets. They were covered in blood. Some of them were carrying others who had collapsed. . . .At the entrance to the citadel there were soldiers standing guard. They were holding clubs as thick as a man’s wrist and were lashing out and hitting anyone who crossed their path. The Jews were pouring out of the entrance. There were rows of Jews lying one on top of the other like pigs whimpering horribly. The Jews kept streaming out of the citadel completely covered in blood. We stopped and tried to see who was in charge of the Kommando. “Nobody.” Someone had let the Jews go. They were just being hit out of rage and hatred.

“Nothing against that,” Landau decides—“only they should not let the Jews walk about in such a state.”

A similar gauntlet, but more lethal, was organized four days later in Lvov by officers of the Waffen-SS Viking division following the shooting death of the commander of one of the division’s regiments. Günther Otto, a twenty-one-year-old butcher assigned to the train that carried fresh meat for the troops, described the experience in a Nuremberg Trial deposition after the war:

The members of the meat train and the bakery company systematically rounded up all Jews who could be found based on their facial characteristics and their speech, as most of them spoke Yiddish. ObersturmführerBraunnagel of the bakery company and Untersturmführer

17

Kochalty were in charge of rounding them up. Then a path was formed by two rows of soldiers. Most of these soldiers were from the meat train and the bakery company, but some of them were members of the 1st Mountain Hunter Division. The Jews were then forced to run down this path and while doing so the people on both sides beat them with their rifle butts and bayonets. At the end of this path stood a number of SS and Wehrmacht officers with machine pistols, with which they shot the Jews dead as soon as they had entered into the bomb crater [being used as a mass grave]. [Superior officers of the regiment] were part of this group that conducted the shootings. About fifty to sixty Jews were killed in this manner.

The Viking division “had been indoctrinated with anti-Semitic thoughts in Dachau and Heuberg” by a major and a corporal, Otto explained, “but we were never told that the anti-Semitic program went as far as extermination — only that the Jews were parasites and responsible for the war.”

The Wehrmacht also occupied Tarnopol on 2 July 1941 and continued to encourage its men to unmilitary murder in disproportionate reprisals. In Tarnopol as well, Einsatzkommando 4b under SS-Standartenführer Günther Herrmann, a Göttingen-educated lawyer, “inspired” (as a report called it) Bandera nationalists to pogroms. One particularly heinous inspiration was recorded in the diary of a German general, Otto Korfes, on 3 July:

We saw trenches 5 m[eters] [16 feet] deep and 20 m [66 feet] wide. They were filled with men, women and children, mostly Jews. Every trench contained some 60–80 persons. We could hear their moans and shrieks as grenades exploded among them. On both sides of the trenches stood some 12 men dressed in civilian clothes. They were hurling grenades down the trenches. . . . Later, officers of the Gestapo told us that those men were Banderists.