Masters of Rome

Authors: Robert Fabbri

MASTERS OF ROME

Robert Fabbri

read Drama and Theatre at London University and worked in film and TV for 25 years. He was an assistant director and worked on productions such as

Hornblower

,

Hellraiser

,

Patriot Games

and

Billy Elliot

. His life-long passion for ancient history inspired him to write the

Vespasian

series. He lives in London and Berlin.

Also by Robert Fabbri

THE VESPASIAN SERIES

TRIBUNE OF ROME

ROME'S EXECUTIONER

FALSE GOD OF ROME

ROME'S FALLEN EAGLE

Coming soon

â¦

ROME'S LOST SON

SHORT STORIES

THE CROSSROADS BROTHERHOOD

THE RACING FACTIONS

THE DREAMS OF MORPHEUS

First published in hardback in Great Britain in 2014 by Corvus,

an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Robert Fabbri, 2014

The moral right of Robert Fabbri to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author's imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 978 0 85789 962 0

Trade paperback ISBN: 978 0 85789 963 7

eISBN: 978 0 85789 964 4

Printed in Great Britain.

Corvus

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26â27 Boswell Street

London WC1N 3JZ

For my friends through life: Jon Watson-Miller, Matthew Pinhey, Rupert White and Cris Grundy; thank you, chaps.

And in memory of Steve Le Butt 1961â2013 who sailed west before us.

Contents

PROLOGUE: B

RITANNIA

,

MARCH

AD 45

PART I: B

RITANNIA

, S

PRING AD

45

PART II: B

RITANNIA

, S

EPTEMBER AD

46

PROLOGUE

B

RITANNIA

, M

ARCH

AD 45

Â

T

HE FOG THICKENED

, forcing the

turma

of thirty-two legionary cavalry to slow their mounts to a walk. The snorts of the horses and jangle of harnesses were deadened, swallowed up by the thick atmosphere enshrouding the small detachment.

Titus Flavius Sabinus pulled his damp cloak tighter around his shoulders, inwardly cursing the foul northern climate and his direct superior, General Aulus Plautius, commander of the Roman invasion force in Britannia, for summoning him to a briefing in such conditions.

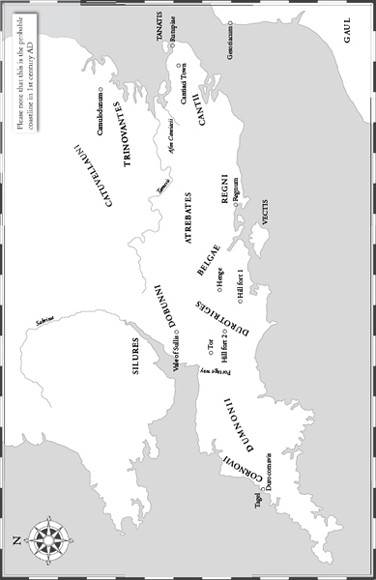

Sabinus had been surprised by the summons. When the messenger, a tribune on Plautius' staff, arrived with a native guide the previous evening at the XIIII Gemina's winter camp on the middle reaches of the Tamesis River, Sabinus had expected him to be bringing his final orders for the coming season's campaign. Why Plautius should order him to travel almost eighty miles south to meet him at the winter quarters of the II Augusta, his brother Vespasian's legion, seemed strange just a month after the legates of all four legions in the new province had met with their general at his headquarters at Camulodunum.

Unsurprisingly, the tribune, a young man in his late teens whom Sabinus had known by sight for the last two years since the invasion, had been unable to enlighten him as to the reason for this unexpected extra meeting. Sabinus remembered that during his four years serving in the same rank, in Pannonia and Africa, he was very rarely favoured with any detail by his commanding officers; a thin-stripe military tribune from the equestrian class was the lowest of the officer ranks, there to learn and obey without question. However, the scroll the young man bore was sealed with Plautius' personal seal, giving Sabinus no choice but to curse and comply; Plautius was not a man to tolerate insubordination or tardiness.

Reluctantly leaving his newly arrived senior tribune, Gaius Petronius Arbiter, in command of the XIIII Gemina, Sabinus had ridden south that morning with an escort, the tribune and his guide, into a clear dawn that promised a chill but bright day. It had not been until they had started to climb, in the early afternoon, up onto the plain that they were now traversing that the fog had started to descend.

Sabinus glanced at the native guide, a middle-aged, ruddy-faced man riding to his right on a stocky pony; he seemed unperturbed by the conditions. âCan you still find your way in this?'

The guide nodded; his long, drooping moustache swayed beneath his chin. âThis is Dobunni land, my tribe; I've hunted up here since I could first ride. The plain is reasonably flat and featureless; we only have to keep our course just west of south and we will come down into the Durotriges' territory, behind the Roman line of advance. Then tomorrow we have a half-day's ride to the legion's camp on the coast.'

Ignoring the fact that the man had not addressed him as âsir' or indeed shown any respect for his rank whatsoever, Sabinus turned to the young tribune riding on his left. âDo you trust his ability, Alienus?'

Alienus' youthful face creased into a frown of respect. âAbsolutely, sir; he got me to your camp without once changing direction. I don't know how he does it.'

Sabinus stared at the young man for a few moments and decided that his opinion was worthless. âWe'll camp here for the night.'

The guide turned towards Sabinus in alarm. âWe mustn't sleep out on the plain at night.'

âWhy not? One damp hollow is as good as another.'

âNot here; there're spirits of the Lost Dead roaming the plain throughout the night, searching for a body to bring them back to this world.'

âBollocks!' Sabinus' bravado was tinged slightly by his realisation that he had neglected to make the appropriate sacrifice to his guardian god, Mithras, upon departure that morning, owing to the lack of a suitable bull in the XIIII Gemina's camp; he had

substituted a ram but had ridden through the gates feeling less than happy with his offering.

The guide pressed his point. âWe can be off the plain in an hour or two and then we'll cross a river. The dead won't follow us after that â they can't cross water.'

âBesides, General Plautius was adamant that we should be with him soon after midday tomorrow,' Alienus reminded him. âWe need to carry on for as long as we can, sir.'

âYou don't like the sound of the Lost Dead, tribune?'

Alienus hung his head. âNot overmuch, sir.'

âPerhaps an encounter with them would toughen you up.'

Alienus made no reply.

Sabinus glanced over his shoulder; he could, again, just see the end of their short column, as the fog seemed to be thinning somewhat. âVery well, we'll press on, but not because of any fear of the dead but rather so as not to be late for the general.' The truth was that the superstitious part of Sabinus' mind feared the supernatural as much as the practical part feared the wrath of Plautius should he be kept waiting too long, so he was relieved that he had been able to retract his order in a face-saving manner. It would not do to have people think that he gave any credence to the many stories of the spirits and ghosts that were said to inhabit this strange island; but he did not like the sound of the Lost Dead and, even less, the thought of spending the night in their dominion. During his time on this northern isle he had heard many such stories, enough to believe there to be a grain of truth in at least some of them.

Since the fall of Camulodunum and the surrender of the tribes in the southeast of Britannia, eighteen months previously, Sabinus had led the XIIII Gemina and its auxiliary cohorts steadily east and north. Plautius had ordered him to secure the central lowlands of the island whilst the VIIII Hispana headed up the east coast and Vespasian's II Augusta fought its way west between the Tamesis and the sea. The XX Legion had been kept in reserve to consolidate the ground already won and ready to support any legion that found itself in trouble.

It had been slow work as the tribes had learnt from the mistakes of Caratacus and his brother, Togodumnus, who had

tried to take the legions head-on, soon after the initial invasion, and throw them back using their superior numbers; this tactic had failed disastrously. In two days, as they tried to halt the Roman advance at a river, the Afon Cantiacii, they had lost over forty thousand warriors including Togodumnus. This had crushed the Britons' resolve in the southeastern corner of the island and most had capitulated soon after. Caratacus, however, had not. He had fled west with over twenty thousand warriors and had become a rallying point for all those who refused to accept Roman domination.