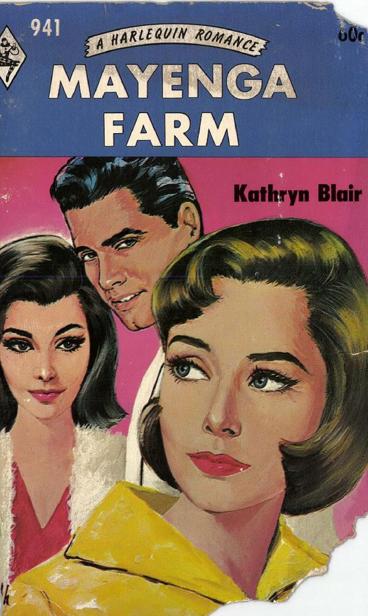

Mayenga Farm

Authors: Kathryn Blair

By KATHRYN BLAIR

Rennie Gaynor found Kent Bradfield’s criticisms of the way she and her father ran their farm quite intolerable. It was true that they were rather poor and unused to South Africa, but Kent’s assurance and good looks annoyed her.

It was not until Rennie’s sophisticated friend Jackie came to stay with the Gaynors and showed a distinct interest in Kent, that Rennie herself found that her feelings for Kent were something deeper than anger.

In “Mayenga Farm” Kathryn Blair describes how these two stubborn people, Rennie and Kent, came to realize that they needed each other.

PRINTED IN CANADA

A special note of interest to the reader

Harlequin Books were first published in 1949. The original book was entitled "The Manatee" and was

identified as Book No. 1 -since then over seventeen

hundred titles have been published, each numbered in sequence.

As readers are introduced to Harlequin Romances, very often they wish to obtain older titles. In the main, these books are sought by number, rather than necessarily by title or author.

To supply this demand, Harlequin prints an assortment of "old" titles every year, and these are made available to all bookselling stores via special Harlequin Jamboree displays.

As these books are exact reprints of the original Harlequin Romances, you may indeed find a few typographical errors, etc., because we apparently were not as careful in our younger days as we are now. None the less, we hope you enjoy this "old" reprint, and we apologize for any errors you may find.

Harlequin Romances

920—THE MAN AT MULERA

941—MAYENGA FARM

954—DOCTOR WESTLAND(Originaiiy

published under the title: "The Affair in Tangier")

972—BARBARY MOON 988—THE PRIMROSE BRIDE 101 2—NO OTHER HAVEN 1 038—BATTLE OF LOVE 1059—THE TULIP TREE 1083— DEAREST ENEMY 1107—THEY MET IN ZANZIBAR 1 148—FLOWERING WILDERNESS

Many of these titles are available at your local bookseller, or through the Harlequin Reader Service.

For a free catalogue listing all available Harlequin Romances, send your name and address to:

HARLEQUIN READER SERVICE,

M.P.O. Box 707, Niagara Falls, N.Y. 14302 Canadian address: Stratford, Ontario, Canada.

or use order coupon at back of book.

by

HARLEQUIN BOOKS

Originally published by Mills &Boon Limited, 50 Grafton Way, Fitzroy Square, London, England

Harlequin edition published August, 1965

Reprinted 1971 Reprinted 1972 Reprinted 1974

AS the characters in this book have no existence outside the imagination of the Author, and have no relation whatsoever to anyone bearing the same name or names. They are not even distantly inspired by any individual known or unknown to the Author, and all the incidents are pure invention

RENNIE stood back to admire the bookshelves, three tiers of them in two long sections, one flanking each side of the false brick fireplace.

"They fit perfectly," she exclaimed. "I can't wait to get your books arranged and to buy some of those pieces of Dutch Gouda pottery to go on top. Perhaps we’d better do without the pottery till after the harvest, though," she added a trifle anxiously. "It's rather expensive. But you’ve made a marvellous job of the shelves. I do like the way they curve down at the ends in two perfect shoulders."

Her father smiled. "A labor of love, my dear, for both of us. The idea was yours and I confess that if I must have an outdoor hobby, a simple bit of carpentering is more in my line than racing between the maize fields on horseback. I'm not saying, mind you, that horse-riding isn’t excellent exercise for one of your age, but I take my pleasure more sedately." Adrian broke off, to gain further silent satisfaction from his craftsmanship. "You shall have at least two pieces of Gouda, Rennie, and not of a piffling size, either. I insist."

"Just two." She was reluctant to relinquish the picture which had taken shape in her mind. "We’ll leave the toby jugs on the mantelpiece but eliminate that cubist-looking lamb." Critically, she surveyed the expanse of polished floor. "If we could afford one really large Mirzapur rug, these two small ones could go into your bedroom, one each side of the bed."

"My bedroom is entirely comfortable as it is. His glance roved the lounge. "In my opinion we’ve done very well for one year. We started with nothing, remember." He paused and once more eyed the empty bookshelves. "By the way, my dear, isn’t it time we woke up the bookseller in Gravenburg? My books may already have arrived."

"I’m going to the store. If you like, I’ll drive on into town and make enquiries."

"Thank you, Rennie. I’d be glad if you would."

His smile pleasant and a little withdrawn, Adrian Gaynor put on his pipe, set a match to it and wandered back to the workshop to pack away his tools. Though he fully appreciated the necessity for open-air interests, he would not be sorry to get back to his study of South African literature.

As her eyes followed him, Rennie’s red mouth curved affectionately. Adrian was no plantation boss, but she did wish that in spite of lack of capital and enterprise, they might reap an abundant harvest just this once. He really did deserve it, and if such a miracle were to happen he could buy all the books he coveted, and she might herself rise to something modern in the way of a suit or cocktail frock. Not that she had much use for either in this subtropical corner of the Northern Transvaal, but the possession of a slick garment or two did give one’s ego a fillip.

This morning Rennie allowed herself a rare moment's reflection upon what might-have-been . . . what was until eighteen months ago, when her mother had died. A villa in St. John’s Wood, her father librarian in an adjacent London suburb and she one of his assistants and wonderfully happy in the work. Then tragedy in its most poignant form, and Rennie and Adrian adrift in the dark, inadequate for a while to console each other. For weeks they were out of touch, unable to grope their way to common ground which would not crumble beneath their feet.

And then one morning, after a night of pacing, Adrian had said, "There’s only the two of us. Why shouldn’t we sell up and go abroad, Rennie? South Africa, I should think—plenty of room there. We’ll farm and try to strike roots."

The absurdity of two people who had lived among books seriously considering large-scale farming in the veld had not struck Rennie at the time. Plenty of men were forsaking office desks for more adventurous occupations in the Dominions, and Adrian, not yet fifty and well-read, appeared to have much in his favor. Anything was better than the strange stupor which had settled over them.

They had sold up and come to Durban, met the inevitable real estate salesman and, on his recommendation, had bought a large tract of land seven hundred miles away. Splendid growing soil, he had told them, which bordered a tributary of the Limpopo, so there would be no lack of water, which was an immense advantage.

Armed with all the bulletins on maize-growing even issued by the South African Department of Agriculture they had come north, erected a mud-brick house with a corrugated iron roof and block-wood floors, installed rain tanks and a watermill, and furnished the five rooms in rattan and teak from Gravenburg.

And here they were, by no means prosperous, wondering all the time whether they wouldn’t have done better with cotton or soya beans, or anything but the maize which, last season, had happily housed huge families of the stalk-borer pest. Three bags to the acre had been a frightful blow. This season they had ploughed and bought soil fumigants, paid well for guaranteed seed, and temporarily engaged an Afrikaner to superintend the planting. And they had taken the precaution of mixing the crops. Surely they would not be let down again.

She ran along the corridor, past George, whose black woolly head with an artificial parting shaved down the centre circled jerkily as he polished the floor, and through the kitchen to the pantry, where she kept her stores list. Carefully, she cheated each item and queried a couple which she thought might be left over for the present. They rather depended on whether her father's books were available.

Rennie got out the car, a doubtful acquisition from Durban, and rocketed away along the dusty track which crossed the river by a stone bridge and linked up with the main road to Gravenburg. This other side of the river there were more trees and the air had a softer, more merciful quality, though at this time of day, with the sun burning almost due overhead, there was little shade.

Adrian’s favorite bookshop—in fact the sole shop of its kind in Gravenburg—could report no success with his order. When the books did arrive from Johannesburg, said the old man with his genial smile, they would be sent at once to Mayenga. He knew Adrian’s impatience over such things. So Rennie bought her full quota of stores and decided, in a mood of expansiveness, to drive the long way home, recrossing the bridge and following the trail alongside the river.

She swung the car round the bend of the river and slowed at the sight of unfamiliar activity. Natives were busy on the other side tearing up the ferns and vines between the trees, lopping thin branches and loading them into a smart new truck. Oh, heavens, what a pity. She had always enjoyed the jungly look of the other bank, the big red vine-flowers pasted flat on the dark vegetation and the queer rubbery plants with exposed, rake-like roots. She and Adrian had often picnicked here, where the cottonwood log thrust into the water, and she could sit on it and dip her toes while he browsed over a book. They had conjectured about the age and height of the trees.

Rennie had known three months ago that the land was sold. One Sunday, on their way to the foothills of the mountains, she and Adrian had passed the half-finished homestead, which lay back from the Gravenburg road, higher up than the spot at which their track joined it. The dwelling was in modern Colonial style, very well built, with actually a second storey under a green-tiled roof, and pergolas erected the whole length of the drive. Already bougainvillea roots were established at the foot of the pillars, and palms and shrubs planted in the garden. Obviously, the owner did not intend wasting any growing time. Now, his clearing operations had reached the river and were spreading very quickly along its bank.

Rennie slid out on to the path, stepped through a border of tough grass and jumped lightly on to the flat worn surface of the log. It was a grand stretch of river, narrow here, but widening within view and disappearing with an enchanting distant gurgle over a shallow ledge. Burdened branches arched over it and dipped their emerald tips.

"Mfana! Hold it taut. Cinile! Fana galo."

Rennie's head turned swiftly. Lord, what a tall man, and what a width across the back of his shoulders. He and a native were stretching a steel tape such as surveyors use between one tree and its fellows, and apparently this particular specimen was condemned. The tape zipped back into its metal cover, and the man twisted. Darkly tanned, his cheekbones a little high, and a cleft chin. Rennie got the impression that beneath the straight blade brows his eyes must be disconcertingly blue and discerning. Maybe it was the aloofness in his expression which made her decide that she preferred men less dark and unsmiling.

"How d’you do!" he called across the narrow band of water, in a voice a little less chilling than his demeanor. "I’m your new neighbor. Kent Bradfield, forestry man."

"Rennie Gaynor," she returned, unable to quell the habitual smile. "I shall miss the trees."

"We’re only felling a few — just enough to give the others a chance, but if you’re needing any timber for fencing, let me know. I’ve an abundance of it."

Was it merely a neighborly suggestion, or had he noticed Mayenga’s lack of good boundaries? On the point of apologizing for it, Rennie paused.

"The usual split poles look rather grim," she said. "I’d prefer to plant a boundary of trees when we can . . ." she had been about to say, "when we can afford it," but she changed to: "when we can get hold of the sort we want."

His attention on his boys, he asked, "What kind do you want?"

"Evergreens, if possible — big trees like blue gums and pines, and a date palm here and there to soften the view. "

"Gum trees soak all the moisture from the land. They should never be grown on farms. And palms need attention while they’re

young. They grow best in gardens."

His complete casualness piqued Rennie. She would like to have said something devastating enough to imprint a frown or a smile on that brutally handsome face— preferably a ferocious frown. Now why on earth should she want to annoy a man she had met for the first time only five minutes ago? What had happened to her usual debonair acceptance of new acquaintances?

Politely, she asked, "Is your house finished yet?"

He nodded negligently. "Finished and furnished. And it faces north."

No mistaking the emphasis. Rennie hadn't lived for a year at Mayenga without discovering that their cream-washed farmhouse fronted the wrong way. She and Adrian had been guided simply by the distant pinnacles and undulations of cedars and huge-girthed baobabs which would be visible from the stoep and through the French door. They had agreed that it would be senseless to waste so much beauty on the back windows, and promptly decided to face south, away from the sun. Consequently, the kitchen and bedrooms sweltered while a sepulchral chill permeated the front rooms. The chill was only comparative, for Mayenga lay within the hot belt, but Rennie, like most people who settle in sunny places, almost unconsciously preferred the warmth of the back stoep to the dim coolness of the front.