Meatonomics (6 page)

Authors: David Robinson Simon

In the battle for the souls of the nation's eaters, it's not enough merely to disseminate a message. Like a wartime radio monitor, one must also carefully analyze and decode messages from the opposition.

The industry approaches its task with vigilance. Regularly assessing consumer attitudes toward meat and dairy, industry monitors are quick to take corrective steps when needed. With that directive in mind, the National Pork Board recently surveyed kids to determine whether they had been influenced by animal advocacy organizations. Surprisingly, more than half the kids had heard of such groups, and one-fourth said that messages from the groups had influenced their eating habits. “We're keeping a close eye on these activist groups and their messages,” says Traci Rodemeyer, director of pork information for the National Pork Board, “and we're prepared to take action if they escalate their efforts to target children.”

10

In 2010, the American Meat Institute (AMI), one of the main trade organizations promoting the meat industry, surveyed adult Americans to gauge their attitudes toward a set of troubling messages circulating among the meat-buying public.

11

Among others, the messages included the factually accurate propositions that eating red meat increases heart disease risk and that Americans eat more meat than recommended. For meat producers, the survey results were cause for alarm. Consumers voiced concern about these and other issues, and the meat industry got a favorability score of only 48.7 out of 100. (That's almost two points worse than the mediocre approval ratings of steroidal slugger Barry Bonds.

12

) AMI sprang into action. “A multiple media curriculum was developed to debunk these myths,” wrote AMI's director of scientific affairs Betsy Booren. “The messaging was factual, positive, and consumer and media friendly.”

13

One of the consumer-friendly tools AMI deployed in its campaign is the

Meat Mythcrushers

website, which seeks to correct the “myths and misinformation” Americans learn about food from “news media, books and movies.”

14

The site serves as a showcase for some of the industry's most interesting messaging tactics. For example, we learn that a “very large 2010 study” showed dietary saturated fat

does not

cause heart disease. The study, of course, is the dubious Siri-Tarino paper discussed in the prior chapter.

Even more interesting is the site's treatment of a well-documented problem: American overconsumption of meat. The site purports to

debunk the overeating “myth” by pointing out that men's and women's daily consumption levels of meat and poultry, averaging 6.9 ounces and 4.4 ounces, respectively, are well within the daily range of “five to seven ounces” recommended by the USDA.

15

If you've ever wondered about the meaning of

truthiness

, the term popularized by Stephen Colbert, this assertion nails the definition. While it has certain elements of truth, the message is downright false in one respect and misleading in another. First, USDA guidelines recommend a maximum of 6.5 ounces, not seven, from the protein foods group per day.

16

It's easy to see why AMI chose to round up to seven: this allows the male consumption figure of 6.9 to squeeze just inside the range.

Worse, the AMI's daily consumption figures exclude two common animal foods listed in the USDA's protein foods group: fish and eggs.

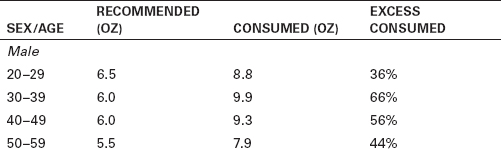

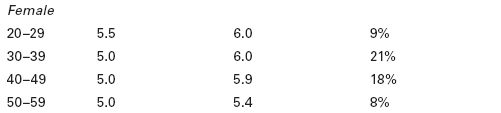

Table 2.1

shows the effect of adding these foods to the calculation. In fact, in virtually every American demographic, consumption of animal foods is well

above

USDA recommendations. Note that this table does not reflect

total

protein consumption—those figures are higher still because they include vegetable proteins like nuts and beans, and dairy, which the USDA oddly doesn't treat as protein and insists on placing in its own category for recommended daily servings. Nevertheless, the data for recommended and actual daily servings for meat is alarming. For males between twenty and fifty-nine, who routinely eat from one-third to two-thirds more than the daily recommended amount of meat, eggs, and fish, the AMI's reassuring suggestion that they're eating the right amount is downright dangerous.

TABLE 2.1:

US Daily Recommended and Actual Consumption of Meat, Eggs, and Seafood

17

Sometimes industry's aggressive messaging tactics lack even the thin veneer of truthiness. In 2011, People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) sued the California Department of Food and Agriculture and the California Milk Advisory Board over the latter's claims that dairy cows in California are “happy.” This message is central to the Milk Board's advertising campaign, which seeks to distinguish California dairy products from out-of-state goods based on the premise that cows are happier in California than elsewhere. In selling this point, the promotional messaging claims, “California dairy cows live happy all year long,” and California dairy producers “work day in and day out to ensure their cows are healthy and comfortable.”

18

Commercials promoting these assertions feature grassy valleys, rolling hills, and cows grazing freely in huge pastures. They end with a voiceover: “Great milk [or cheese] comes from Happy Cows. Happy Cows come from California. Make sure it's made with Real California Milk [or Cheese].” In fact, it seems that few American dairy cows have much reason to be happy (whether they live in California or elsewhere). According to research cited in the lawsuit, dairy cows raised in US factory farms (where most American milk is produced) routinely encounter a variety of difficult circumstances including:

- Johne's disease, a chronic wasting illness that affects two-thirds of all US dairy cows and causes severe weight loss and diarrhea.

- Routine branding, and the burning of budding horns—both done without anesthesia, which peer-reviewed studies and the American Veterinary Medical Association have described as “acutely painful and stressful” for the cows.

19 - Spending most of their lives crammed into tiny, concrete-floored stalls fitted with brisket boards, which prevent the animals from reclining comfortably.

20 - Aggressive milking quotas that make industrially raised cows more likely to “die prematurely and/or suffer from lameness, mastitis, respiratory disease, metabolic problems, reproductive complications and other sicknesses than ‘normally’ producing dairy cows.”

21

In fact, despite such widespread reasons for bovine unhappiness, it seems that most dairy cows would nonetheless be “happier” almost anywhere

other than

California. Specifically, California cows “have a statistically greater chance of experiencing discomfort, suffering from painful diseases and/or of dying prematurely, than cows elsewhere in this country.”

22

It just doesn't sound like any of the nation's industrially raised dairy cows, least of all those in California, have much reason to be happy. PETA tried to bring this lawsuit for more than a decade, although the first few complaints they filed were dismissed for procedural reasons. In the latest filing, PETA won an important, early-round victory when the judge ordered the defendants to release thousands of pages of documents claimed to be trade secrets. At this writing, the lawsuit is still pending.

In 2008, the Physician's Committee for Responsible Medicine (PCRM) launched a campaign to educate people about the health dangers of processed meats. As a matter of fact, dozens of studies published in peer-reviewed medical journals establish that eating processed meats is linked to cancer.

23

But rather than address this copious research, AMI responded with a press release designed to deflect attention from the underlying science. The release's main theme was evident from its title: “Media Needs to Check Background of Pseudo-Medical Animal Rights Group and Cease Coverage of Alarmist and Unscientific

Attack on Meat Products.”

24

Such an ad hominem, or to-the-man, personal attack is a logical fallacy that ignores the merits of the message itself. Stanley Cohen, professor of sociology and author of the book

States of Denial

, calls this a denial technique used by those who:

try to deflect attention . . . to the motives and character of their critics, who are presented as hypocrites and disguised deviants. Thus the police are corrupt and brutal, teachers are unfair and discriminatory. By attacking others, the wrongfulness of [one's] own behavior can be more easily repressed or lost to view.

25

AMI is no stranger to this tactic. In another example, the trade organization issued a press release in 2001 responding to a petition that various groups had filed with the USDA asking the agency to enforce the federal Humane Methods of Slaughter Act. Rather than address the petition's many eyewitness accounts of inhumane practices in the slaughter process, which were signed under penalty of perjury, AMI attacked the petitioner organizations themselves. “It is important to note,” said AMI, “that the credibility of some of the petitioners is in serious doubt.”

26

AMI is not alone in seeking to deflect attention from legitimate, anti-industry messages by questioning the messengers' motives, credibility, or integrity. In the next chapter, we'll see further evidence of institutional efforts to marginalize those whose messages could harm industry. For example, animal agribusiness has persuaded Congress and most state legislatures to pass legislation that brands those who interfere with factory farms as “terrorists.” This is a powerful method not only of curbing activism, but also of discrediting activists and their message.

Is animal protein a life-enhancing elixir? From a young age, we're taught it fosters health, growth, vitality, virility, and sometimes even weight loss. The alternative to getting plenty of it, we're told, could be protein deficiency. Never mind that the typical American has never had—nor ever will have—protein deficiency and has little idea what its

symptoms might be. We've heard of it, we're scared of it, and whatever the heck it is, we don't want it.

Spurred by the most basic force of meatonomics—the drive to sell more meat and dairy—animal food producers use our protein fears to their advantage. For example, a beef checkoff website suggests when deciding how much meat to eat, we go beyond the bare minimum needed to “prevent protein deficiency.”

27

Elsewhere on the site, we're warned:

HEALTH ALERT: Sarcopenia.

Sarcopenia is a condition associated with a loss of muscle mass and strength in older individuals. . . . While there is no single cause, insufficient protein intake may be a key contributor to this condition.

28

The key phrase here is

may be.

In fact, the research linking sarcopenia to protein deficiency is spotty and inconclusive. A 2001 study published in

The Journal of Laboratory and Clinical Medicine

found simply, “Decreased physical activity with aging appears to be the key factor involved in producing sarcopenia.”

29

We're regularly bombarded with protein messages like these. How accurate are they? What are the health consequences of following them? Because protein is such an important nutrient, and emerging research presents an array of new findings on the subject, it's worthwhile to assess the protein messages that influence our consumption habits.

Here's something to chew on: a peanut butter and jelly sandwich on whole wheat bread contains more protein (14 grams) than a McDonald's hamburger (13 grams). Many consumers think plant foods contain little protein—in any case, not enough to meet our daily needs. But a closer look suggests the animal food industry may be overhyping animal protein in ways that are clinically unsupported.

For humans, the best guidance on protein requirements is contained in a 284-page report produced jointly by the United Nations and

the World Health Organization (WHO).

30

According to this report, an adult needs 0.66 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight per day.

‡

For a 170-pound adult, this is about 50.8 grams of protein per day. An omnivore could fill this quota with just one chicken breast and one drumstick per day, although among American consumers, such restraint is rare. Males between twenty and fifty-nine, for example, typically consume more than 100 grams of protein daily—twice the level recommended by WHO.

31