Meditations on Middle-Earth (22 page)

Read Meditations on Middle-Earth Online

Authors: Karen Haber

Tags: #Fantasy Literature, #Irish, #Middle Earth (Imaginary Place), #Science Fiction & Fantasy, #Welsh, #Fantasy Fiction, #History and Criticism, #General, #American, #Books & Reading, #Scottish, #European, #English, #Literary Criticism

I ended up reading the series every year of my adolescence. I read it until those first paperbacks wore out; I read it until I practically had it memorized, and—unfortunately—could not look at it again for a long while, having become familiar with every twist and turn, every poetic phrase.

I learned later that I wasn’t the only one to do this. I even read a book once where, to demonstrate what a nerd one of the characters was, the author mentions that the character read The Lord of the Rings every year. Okay, so we’re nerds. I made myself a cloak once; I even went out with a guy who called himself Bilbo. Guilty. But what the author of this book—I can’t remember the title, but it was mainstream, obviously—failed to understand is how powerful The Lord of the Rings actually is.

The question, though, is why. Why do people read and reread these books? Why are they so powerful? What do we get from them that we can’t get anywhere else? How did one man working alone manage to call into being an entire genre, an entire publishing industry?

My guess is that it’s because we need myth. Not just because myths are entertaining stories, or because some of them come attached with a moral. We

need

them, the way we need vitamins or sunlight.

I read The Lord of the Rings at the tail end of the sixties, when it seemed that everyone was busily searching for a myth, a religion, a way to make some kind of meaning out of their world. My school was overrun with kids carrying the Bible, or books by Alan Watts, or Chairman Mao’s little red book. There was a sense that our parents had failed us somehow, that we had missed something, that there was a larger world out there we had never been told about.

We had grown up in the fifties; our parents had survived the Depression and the horrors of World War II, and now just wanted to make a life for themselves in the midst of America’s new prosperity. Not for them the troubling questions about myth and meaning, the dragons slithering up from the psyche. Fairy tales became comfortable stories told to children; the dwarfs of

Snow White

were no longer mysterious and sometimes frightening earth-dwellers, but cute little men named Grumpy and Sneezy. Even religion became something we thought about for a few days each year and forgot the rest of the time.

The idea was that science had triumphed, that we lived in an Age of Science. Diseases that had terrified people for centuries had been nearly wiped out; nuclear power was about to give us unlimited sources of energy.

The Age of Science certainly brought a lot of benefits—I’m not saying that smallpox and polio were good things. But somehow the idea grew that science and myth could not coexist, that myth was the same as superstition, and had to be suppressed. And I think this loss of myth was one of the reasons my generation searched so hard and went, some of them, down such disastrous paths.

Myths had started their decline long before the fifties, though. Tolkien himself, in his famous essay “On Fairy-stories,” puts the beginning somewhere around the Elizabethan Age. Once upon a time, fairies had been called the Fair Folk to placate them, and people thought of them as capricious and unpredictable, beautiful and terrifying, anything but fair. But in the works of Michael Drayton and Shakespeare himself, they became tiny, dainty, merely pretty. They lost their power to astonish and frighten; they dwindled, both in stature and importance. They became a subject for children and, eventually, as Tolkien puts it, were “relegated to the nursery.”

Not surprisingly, this happened at about the same time that people were beginning to understand certain things about their world, were beginning to experiment, were starting on the road that would take them from alchemy to chemistry, from astrology to astronomy.

The need for myth became especially acute after World War I, when all the certainties of the old values were swept away, when, not coincidentally, Tolkien began his tale. Part of his genius was that he realized this hunger still existed, despite all the marvels of the modern world. He knew that people need epic stories of journeys, dragons, treasure, magic, wonders, terrors, loss, and redemption, of heroes stretched nearly beyond their capacity for endurance. We need them because they’re magnificent stories, of course, tales that have been told as long as people existed. But we also need them because they are stories about the hero who journeys into a dark place and comes out transformed, and that is a story we all know intimately, a story each of us experiences in his or her life. Those dragons are our dragons, those magical helpers our helpers. And sometimes the dragons are inside us, a part of us, and this is the most terrifying struggle of all. No wonder an entire generation wanted nothing to do with myth.

If that was all, we’d probably never have heard of this man Tolkien. But his genius also showed itself in the way he was able to satisfy that hunger. Working in the twentieth century, at a time of cars and airplanes and radios, he revived an old form and somehow made it speak to the present. He spent, literally, decades constructing his world, making it consistent, giving it languages and poetry and history and art, making it so real we might believe that he had discovered it rather than invented it. He gave it characters of stature—metaphorical if not literal—people who fit the grandeur of the place. And he set in motion a story that we read again and again.

How did he do it? How was he able to write an epic in a time when epics were all but forgotten? How did he tap into the collective unconscious of so many people? I don’t know. Sorry. You might check Joseph Campbell’s

The Hero with a Thousand Faces

, another response to the lack of myth in the twentieth century. Campbell gives a template for the hero’s journey, from the Call to Adventure to the Descent into Darkness—the Night-sea Journey—and finally the Emergence of the Hero Reborn, and you might note that there are at least three of these descents in The Lord of the Rings: Gandalf in Moria, Frodo’s and Sam’s journey into Mordor, and Aragorn in the Paths of the Dead. But Tolkien, of course, didn’t use a template—for one thing, The Lord of the Rings was nearly finished when Campbell’s book came out. More importantly, the unconscious does not follow rules; it cannot be forced into a template.

Tolkien himself, in the introduction to The Lord of the Rings, says that he was writing a story “that would hold the attention of readers, amuse them, delight them, and at times maybe excite them or deeply move them. As a guide I had only my own feelings for what is appealing or moving. . . .” I think that’s the closest we’ll come to understanding how he did it. Somehow he went deep into his unconscious—another Descent into Darkness—went into the part of his mind where the stories come from, and he returned to the everyday world with this one. That’s why he was a genius; there’s really no explaining them.

There is one explanation for his success I can give, though, one small piece of the mystery I can illuminate. I think some of it has to do with language. An epic tale needs an epic voice, a poetic voice, a voice raised above the babble and trivia of the everyday world. There should be a hint of the ancient world in this voice, an understanding that the storyteller is dealing with a heroic age, with people who were, if not better than,

more

than us. (But only a hint. A little archaism can go a long way.)

Tolkien, a professor of languages and a connoisseur of words, knew all about this; so did Homer, and the author of

Beowulf

, and whoever wrote the more poetic parts of the Bible. He turned to these examples as he wrote, an achievement that is all the more impressive when you realize that he was writing in a time that worshiped Hemingway and his stripped-down, no-nonsense prose. (Geniuses, of course, pay no attention to fashions.) Listen to these lines, to the rhythms, to the spell he is weaving here:

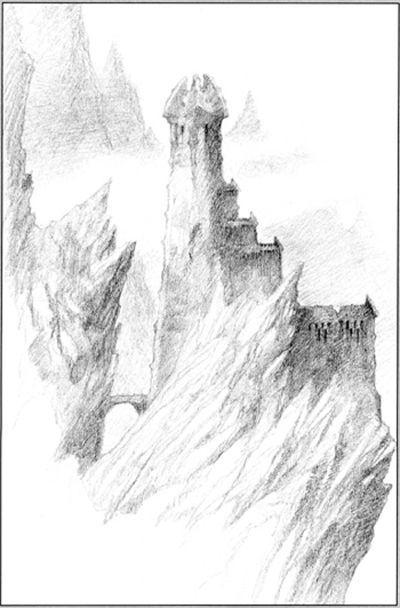

CIRITH UNGOL

The Return of the King

Book 4, Chapter I: “The Tower of Cirith Ungol”

He [Frodo] stood as he had at times stood enchanted by fair elven-voices; but the spell that was now laid upon him was different: less keen and lofty was the delight, but deeper and nearer to mortal heart; marvellous and yet not strange. “Fair lady Goldberry!” he said again. “Now the joy that was hidden in the songs we heard is made plain to me.”

The Fellowship of the Ring

“Gibbets and crows!” he [Saruman] hissed, and they shuddered at the hideous change. “Dotard! What is the house of Eorl but a thatched barn where brigands drink in the reek, and their brats roll on the floor among the dogs? Too long have they escaped the gibbet themselves. But the noose comes, slow in the drawing, tight and hard in the end. Hang if you will!”

The Two Towers

“Begone, foul dwimmerlaik, lord of carrion! Leave the dead in peace.”

A cold voice answered: “Come not between the Nazgûl and his prey! Or he will not slay thee in thy turn. He will bear thee away to the houses of lamentation, beyond all darkness, where thy flesh shall be devoured, and thy shrivelled mind be left naked to the Lidless Eye.”

A sword rang as it was drawn. “Do what you will; but I will hinder it, if I may.”

“Hinder me? Thou fool. No living man may hinder me!”

Then Merry heard of all sounds in that hour the strangest. It seemed that Dernhelm laughed, and the clear voice was like the ring of steel. . . .

The Return of the King

If none of that makes you shiver, you might be dead.

The first example describes a small part of the beauty of Middle-earth, the other two its terror. (Tolkien, unlike many writers, was adept at both.) And I wasn’t joking about these pieces making you shiver. The last is especially shiver-inducing to me, a description of heroism against all odds, of triumph, made even sweeter because it is about one of Tolkien’s few female characters. You don’t even have to know what “dwimmerlaik” means; it’s one of those archaisms I talked about earlier, an authentic reminder that we are in another time, another place. By the sound of it (say it out loud), and in context, we understand that it means something foul, something terrifying.

But, you say, there have been many followers of Tolkien, some who slavishly imitated him, and some who went their own way, and these people do not use poetic language. Sometimes the opposite, in fact; sometimes the ineptness of their writing can make you wince. I haven’t kept up with all the writers of epic fantasy—I don’t think anyone can, these days—but the only ones I know of who understand the importance of language are Ursula Le Guin, Patricia McKillip, and Greer Gilman. (Le Guin even wrote a wonderful essay on this subject, called “From Elfland to Poughkeepsie.”) This is a matter very near and dear to my heart, so I hope you will permit me a small rant here.

(But first, a digression. There are some books that are marketed as epic fantasy but are in fact histories, though histories of imaginary places. These have little or no magic, and are concerned with the stuff of history, intrigues and invasions and the like. They are, and should be, written in the language of history. So I can read Guy Gavriel Kay’s novels with pleasure and without ranting—much to the relief of my husband, who’s heard the rant a few times too many—and I’m having a very good time with George R. R. Martin’s series.)

After I read The Lord of the Rings, I looked around for more of the same. At the time there seemed to be very little that provided the same thrill: some children’s books, the Earthsea series, Lin Carter’s amazing Ballantine Adult Fantasy series. Finally, at the end of the seventies, a number of books came out that were strongly influenced by The Lord of the Rings.

“Strongly influenced” may be understatement; there are scenes in at least one of these that seem to have been lifted in whole from Tolkien. I was working in a bookstore when this book came out, and I was very excited at the advanced publicity. As I said, I was starved for fantasy, and there are only so many times you can reread Tolkien. We ordered a display, what publishers call a “dump” (which gives you some idea of how publishers feel toward their books), containing, I think, eighteen copies. I got an advanced reading copy, settled down to be enchanted, and found myself reading a pale imitation of The Lord of the Rings.

I once felt very bitter toward this book; I thought (and still think, somewhat), that it is at least partly to blame for all the cheap tripe that came later. Now, though, I have a different view, a view I incline to in my less cynical moments. A myth is a story of a hero’s journey into darkness, and his or her return. All myths are the same in this way; it is only the trappings that are different. Perhaps the author of this book, like all of us, was moved by this story, and moved to retell it; perhaps in retelling it he was more like a bard of old, singing a story he had heard to a transfixed audience around a fire. Myths were once told and retold, changed and rechanged; intellectual property is a fairly recent concept. That he proved to be such a poor bard compared to the master does not change the nature of the tale.