Meditations on Middle-Earth (3 page)

Read Meditations on Middle-Earth Online

Authors: Karen Haber

Tags: #Fantasy Literature, #Irish, #Middle Earth (Imaginary Place), #Science Fiction & Fantasy, #Welsh, #Fantasy Fiction, #History and Criticism, #General, #American, #Books & Reading, #Scottish, #European, #English, #Literary Criticism

Sir Thomas Malory and

Le Morte d’Arthur

came centuries before Tolkien. So did Théroulde’s

Song of Roland

. Bram Stoker and Edgar Allen Poe did some splendid work on the borderlands between fantasy and horror, while William Morris created worlds vast and wondrous, distant precursors to Middle-earth.

In this century, Lord Edward Dunsany, James Branch Cabell, and E. R. Eddison each put his own stamp on the literature of fantasy. The importance of Robert Ervin Howard and his Hyborian Age cannot be overestimated, nor that of Fritz Leiber, who went Conan two better with his Fafhrd and the Grey Mouser. In a very different tradition one finds Gerald Kersh, John Collier, Thorne Smith, Abraham Merritt, and Clark Ashton Smith.

Even during his own lifetime, Tolkien had formidable rivals. While he was telling his tales of Middle-earth, his fellow Inkling C. S. Lewis was shaping Narnia. Elsewhere in England, Mervyn Peake was creating the great gloomy castle of Gormenghast, and across the sea in America the incomparable stylist Jack Vance was writing his first tales of the Dying Earth.

Yet it was Middle-earth that proved to have the greatest staying power. Fantasy had existed long before him, yes, but J. R. R. Tolkien took it and made it his own in a way that no writer before him had ever done, a way that no writer will ever do again. The quiet Oxford philologist wrote for his own pleasure, and for his children, but he created something that touched the hearts and minds of millions. He introduced us to hobbits and Nazgûl, took us through the Misty Mountains and the mines of Moria, showed us the siege of Gondor and the Cracks of Doom, and none of us have ever been the same . . . especially the writers.

Tolkien

changed

fantasy; he elevated it and redefined it, to such an extent that it will never be the same again. Many different flavors of fantasy continue to be written and published, certainly, but one variety has come to dominate both bookstore shelves and bestseller lists. It is sometimes called epic fantasy, sometimes high fantasy, but it ought to be called Tolkienesque fantasy.

The hallmarks of Tolkienesque fantasy are legion, but to my mind one stands high above all the rest: J. R. R. Tolkien was the first to create a fully realized secondary universe, an entire world with its own geography and histories and legends, wholly unconnected to our own, yet somehow just as real. “Frodo Lives,” the buttons might have said back in the sixties, but it was not a picture of Frodo that Tolkien’s readers taped to the walls of their dorm rooms, it was a map. A map of a place that never was.

Tolkien gave us wondeful characters, evocative prose, some stirring adventures and exciting battles . . . but it is the

place

we remember most of all. I have been known to say that in contemporary fantasy the setting becomes a character in its own right. It is Tolkien who made it so.

Most contemporary fantasists happily admit their debt to the master (among that number I definitely include myself), but even those who disparage Tolkien most loudly cannot escape his influence. The road goes ever on and on, he said, and none of us will ever know what wonderous places lie ahead, beyond that next hill. But no matter how long and far we travel, we should never forget that the journey began at Bag End, and we are all still walking in Bilbo’s footsteps.

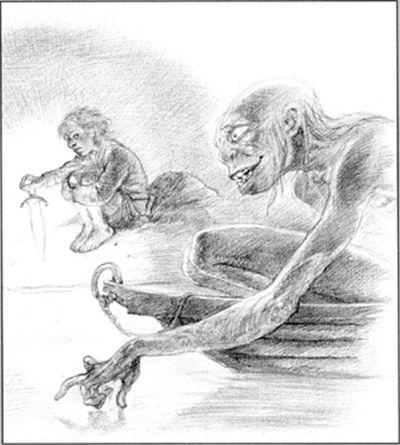

BILBO WITH GOLLUM

The Hobbit

Chapter V: “Riddles in the Dark”

OUR

GRANDFATHER:

MEDITATIONS ON

J. R. R. TOLKIEN

RAYMOND E. FEIST

I

f you’ve read a single fantasy novel in your life by anyone other than J. R. R. Tolkien, there’s a better-than-even chance at least one reviewer has compared the writer under discussion to Tolkien. Or the jacket blurb, provided by someone in the publisher’s publicity department, makes the comparison. It’s a fact of publishing life, and has nothing to do with the style, ambitions, or the wishes of the author being reviewed or blurbed. Everyone gets compared to Tolkien.

Reviewers often like to use a well-known touchstone to inform their readers of the nature of the book under review. It’s not uncommon to read a review where a mystery is compared to a work by Raymond Chandler, or a western is compared to the work of Louis L’Amour. I have, in turn, been damned by reviewers for being “too much like Tolkien” and for “not being enough like Tolkien.” I’m not exaggerating; and the ironic fact is both those reviews were forwarded to me by my publisher on the same day.

Blurb writers often fall into the trap of using “not since J. R. R. Tolkien has a writer . . .” types of copy. It’s easy, and it lets the potential reader of the book know what to expect: magic, derring-do, high adventure, etc.

Why all the constant comparison to J. R. R. Tolkien? Why is he the touchstone against which all of us in the fantasy field are struck to test our mettle? Simply put, he is considered by many to be the Father of Us All.

I disagree. From my point of view, Fritz Leiber was

my

spiritual father, along with any other number of writers who influenced my childhood: Sir Walter Scott, Robert Louis Stevenson, Rafael Sabatini, Anthony Hope, Samuel Shellabarger, Mary Renault, Thomas Costain, and others. For other fantasy writers it was H. P. Lovecraft, Edgar Rice Burroughs, Robert E. Howard, A. Merritt, or H. Rider Haggard; but Tolkien was our grandfather, no doubt. My view may be in the minority, but then again, I’m a minority of one in any event. But allow me the indulgence of giving you my reasons, and why I think, in the long run, that considering him our spiritual grandfather is a more respectful judgment for working authors today.

When I was a kid, my reading tastes were pretty thoroughly locked into what was then called “boys’ adventure books,” a curious offshoot from classical romances of the nineteenth century. I remember crouching under the covers with a flashlight when I was supposed to be sleeping, or hiding a dog-eared copy of some old novel in my notebook at school and trying to look studious. The teacher would drone on as I read

Captain Blood

by Sabatini, or

Castle Dangerous

by Scott. I remember devouring the entire Leatherstockings Saga by James Fenimore Cooper, and that experience stayed with me so long that when my publisher wanted a rubric for my first trilogy I came up with Riftwar Saga. My children will probably never understand the pleasure I took from those books. If they read any of those titles, they will most likely consider them “quaint.”

The modern realism of the early twentieth century began the decline of this delicious genre. Film and television killed it.

Cooper could spend ten pages describing a one-room log cabin, because his contemporary readers wanted details. They lived in townhouses in Boston or London, and had never seen a cabin or river houseboat. The closest they had come to an indigenous native was the cigar store Indian outside their local tobacconist. The richness of the images provided by the narrator were a requirement for success. Today’s readers have seen Davy Crockett and Daniel Boone reruns, and have no need for that sort of leisurely narrative and detailed description. They want action and dialogue, and they want it now.

As I grew up—I refuse to claim I matured—I discovered “classic” adventure literature—Twain, Cooper, Scott, then the “boys’ adventure” writers. Later I chanced upon science fiction, then fantasy, and embraced them as the logical inheritors of this still-lamented genre. I even remember my introduction to science fiction and fantasy.

In the eighth grade I was required to compose a book report from a novel chosen from an approved list, books made available to my school by generous publishers via a Scholastic publication called “My Weekly Reader.” The list was short and had a couple of Hardy Boys and Nancy Drew titles, as well as some other equally suspect fare; but one title drew my eye:

The Cycle of Fire

by Hal Clement. All I remember about the blurb was the word “adventure,” and I believe “alien” and “space” were also employed. So I checked it off the page and about two weeks later it arrived.

I was hooked. Science fiction was exactly the high adventure fare I had become addicted to, as well as providing a more modern sensibility regarding ethics and morality. Characters weren’t quite as noble as they were in Ivanhoe, nor were the issues of right and wrong always as clearly defined. But, boy, was there plenty of action and a lot of fun stuff that included spies, space battles, and huge empires. E. E. “Doc” Smith was a fair substitute for Sir Walter Scott or Robert Louis Stevenson in my boyish judgment. And by the time I got to Robert A. Heinlein and Isaac Asimov, I was no longer interested in knights in shining armor and pirates on the Spanish Main.

It was about 1966 when I discovered Tolkien. A friend lent me the Ace edition of

The Fellowship of the Ring

. I wasn’t thrilled at first. The references to

The Hobbit

, and the rather leisurely pace of the first chapter, almost put me off. But there was a charm to the narrative; and while I didn’t know who Bilbo or Gandalf were, I was willing to stick around and see what happened to them. After a while I discovered a wonderful nineteenth-century narrative style, and it occurred to me much later that J. R. R. Tolkien had also read “boys’ adventure” novels as a youngster. His choice of style and pace was as if a favorite old uncle were reading me a wonderful tale of knights and quests.

Only the knights weren’t champions of King Arthur’s court; they were interesting little characters called hobbits, and their role in the destruction of the One Ring wasn’t quite Percival and the Holy Grail.

When the Fellowship was destroyed, I put the first book down and said, “What’s next?”

Off I went to the used bookstore I habituated, and there I found the second volume,

The Two Towers

. I also found

The Return of the King

, and decided to pick that up as well, as I figured I’d probably want to finish the entire story.

Within a day or so I had neglected my studies, and my other obligations, to plow through the final two volumes. I then went back to the bookstore and got

The Hobbit

. I didn’t find it as sweeping or as grand a narrative as The Lord of the Rings, but it was fun.

So I went back to the store and said, “What else has he written?”

The answer was, “Nothing.” I know now there were scholarly works and poetry, but this was an American used bookstore, remember. So I said, “What else have you got like this stuff?”

And this is how I came to know Robert E. Howard, A. Merritt, H. Rider Haggard, and Fritz Leiber. I became as hooked on fantasy as I had been on science fiction.

BILBO STEALS THE CUP

The Hobbit

Chapter XII: “Inside Information”

What was it about The Lord of the Rings that hooked me? Foremost it was the classic motif of the underdog, the diminutive Frodo being the only stalwart to endure the breaking of the Fellowship. He, along with Sam, Meriadoc, and Pippin, were willing to brave tribulations that the larger, more “classic” heroic figures were unwilling to confront: the obvious evils of Sargon, the twisted ambition of Saruman, the tragic Gollum, and the insidious lure of the power of the One Ring itself.