Meeting the Enemy (49 page)

Authors: Richard van Emden

As the British mission was about to leave Leipzig, the Germans, in an attempt to ‘make up’ for the decision to free Karl Neumann, informed the British that they would be pursuing another criminal case against two U-boat officers. These men had been party to an indisputably criminal attack against another hospital ship, the

Llandovery Castle

, in which survivors, including nurses, had been attacked while sitting in lifeboats. Both officers were found guilty and sentenced to four years in prison. With the ending of this case, the British drew a line under the whole issue of war crimes trials and normalised relations with Germany. Well-documented crimes, such as those against the prisoners sent to the Russian Front in February 1917, were allowed to pass into oblivion.

The British press reported the proceedings and labelled them farcical,

The Times

calling them a ‘scandalous failure of justice’. In the Commons, the government was asked about the light sentences and whether anything was going to be done about the failure of justice.

Sir Ernest Pollock, the Attorney General, who had attended the trials, answered on behalf of the Prime Minister and, while he felt it improper to make a statement when the French and Belgian cases were still in court, he nevertheless added:

Perhaps the Hon. Members may care to know that the sentence which was delivered in my presence excited great dejection amongst the military party of Germany, and the officers there certainly did not think it was a small sentence to have one of their number sent to an ordinary prison to carry out the sentence of 10 months among thieves and other felons.

Listening MPs may have struggled to see why German thoughts and feelings were of any relevance. Surely it was right to presume that sentencing had everything to do with the crimes for which conviction was secured and nothing whatsoever to do with the conditions under which that sentence might be served? It did not really matter. MPs blew off some steam, but there was no appetite to pursue the matter further. Politicians lost interest in the subject of war crimes because the British public lost interest. The war was over.

So did Britain acquire the ‘fruits of victory’ as anticipated by Winston Churchill? If she did, then most Britons did not share in any obvious harvest. Broken families would have to find ways to re-adjust to living with people who had often become strangers especially to their children. It was a re-adjustment made all the harder by the post-war era of austerity. Years of extraordinary financial outlay resulted in the need for fiscal restraint. Unemployment, poverty and depression resulted; returning soldiers’ claims to pensions and support were ungratefully received and frugally rewarded. Historians have debated and will continue to debate the gross and net price of the conflict between Britain and Germany. Both nations were physically and emotionally drained, though Germany had come off much the worse. In 1917 and 1918 it is estimated that Germany lost as many civilians through the effects of hunger and associated illness as Britain lost in battle. What happened to both nations politically and strategically has been well documented. Less well recorded are the myriad stories of lives fractured by continuing physical and mental scars including those caused by enforced separation and isolation: the human face of the Great War.

I would like to thank the enthusiastic and supportive staff at Bloomsbury, particularly Bill Swainson, the senior commissioning editor, for their encouragement and continued belief in my books. I am also very grateful to Liz Woabank for her keen interest and kind assistance, Oliver Holden-Rea, Tess Viljoen, Maria Hammershoy, Holly Macdonald, Paul Nash and Anya Rosenberg for their collective skill in helping to bring

Meeting the Enemy

to publication. I would also like to express my gratitude to Richard Collins for his careful and insightful editorial comments on this, the fifth of my books he has edited.

Especial mention should be made of my excellent agent, Jane Turnbull, whose astute thoughts and insights have been of invaluable help this year; I greatly value her friendship. Once again, I am very grateful to my great friend Taff Gillingham for his technical reading of the text and the discovery, as always, of small but important errors on my part; his kindness is much appreciated. My appreciation also goes to Peter Johnston for excellent additional research work.

My warmest thanks must go to my family: to my mother, Joan van Emden, whose support is unquantifiable and whose deft literary comments are, once again, of immeasurable help. Thank you, Mum. I am indebted also to my wife, Anna, who is a tower of support and who never makes adverse comments other than that I should try to tidy my study now and again - will do!

I would like to thank the following people for permission to reproduce photographs, extracts from diaries, letters or memoirs: Calista Lucy at Dulwich College for background information on Wilford Wells; fellow author Jack Sheldon whose expert knowledge of the German language and German military units helped decipher Wilford Wells’s military records; Christine Leighton, College Archivist at Cheltenham College for her generous permission to reproduce the image of Henry Hadley. I would also like to thank Margaret Tyler and Kevin C. Dowson for permission to reproduce the picture of Major Renwick and fellow officers of the 3rd Infantry Labour Company; Liz Howell for the image of men of the 30th Middlesex Regiment and Private Charles Kuhr, taken at Reading in 1917; Kevin Northover for his picture of fraternisation at Beaumont Hamel and Kevin Varty for the image of Captain Richard Hawkins. Thanks also to Fergus Johnston and Ellen Campbell, both distant relatives of Henry Hadley, and Christopher Jage-Bowler, priest at St George’s Church, Berlin. My gratitude for help and advice goes to my good friends Mary Freeman, Jeremy and Mark Banning for their thoughts and useful tip-offs! Thanks, too, to Dave Empson, William Spencer, Stephen Chambers, Duncan Mirylees and Gaby Chaudry.

As always, I am very grateful to the families of those I have interviewed who have also been most kind in forwarding precious family photographs and documents.

The Kaiser (left) rides alongside his cousin, King George V, during a visit to Potsdam in 1913. Contact between the royal families prior to the war was close but could also be fraught as the race for naval supremacy mounted.

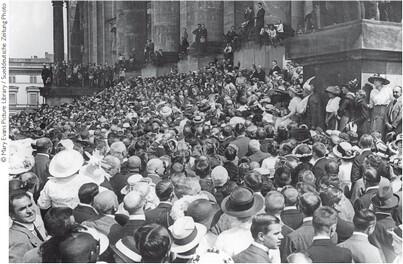

Vast crowds pour onto the Unter den Linden to greet news of the outbreak of war. The Kaiser was profoundly shocked by Britain’s entry into the war on the side of France and Russia.

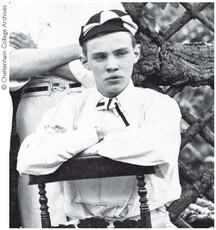

Henry Hadley, pictured at Cheltenham College circa 1880. In 1914 this 51-year-old English teacher, was leaving Germany by train when he was shot and mortally wounded by a German infantry officer. He died at 2.30 a.m., 5 August, acquiring the dubious distinction of becoming the first British citizen to die by enemy hands in the Great War.

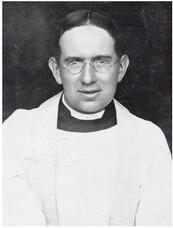

Reverend Henry Williams, priest at St George’s Church in Berlin, left a detailed eyewitness account of the outbreak of war in the capital. He remained in Germany throughout the War, looking after the spiritual needs of British POWs.

Captain William Morritt photographed at a Belgian convent, holding the sword shattered by a German bullet. Wounded at Mons, he was eventually captured, and was shot and killed during an escape attempt in 1917.

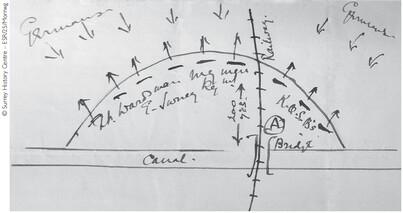

A map drawn by Captain Morritt while recovering at the convent. It shows the East Surreys’ precarious positions during the fighting at Mons, as well as the ground over which he led a bayonet charge.