Men of Bronze: Hoplite Warfare in Ancient Greece (21 page)

Read Men of Bronze: Hoplite Warfare in Ancient Greece Online

Authors: Donald Kagan,Gregory F. Viggiano

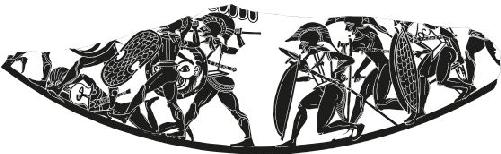

FIGURE 2-9. Alabastron from Corinth, c. 625 BC. Formerly Berlin 3148; after Snodgrass 1964, pl. 33. Source: Snodgrass 1964a (plate 33). Reprinted by permission of Edinburgh University Press,

www.euppublishing.com

.

A battle scene from a badly broken Corinthian krater (

fig. 2-10

) presents a group of at least five hoplites crouching—some stooping slightly, others almost down on one knee—behind a scene of combat. They hold their spears horizontally in an underarm grip, or rest them on the ground, pointing diagonally forward and upward. These rear

ranks are not represented in the way one would expect to see in the classical phalanx. They seem closer to the relatively passive “crowd of companions,” waiting some way behind the “frontline fighters,” which is often mentioned in the

Iliad

. The scene may be taken either as “heroic” or, as Van Wees has suggested, a reflection of the looseness of the battle order even in the early sixth century.

31

FIGURE 2-10. Middle Corinthian krater, c. 600–575 BC. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of John Marshall, 1912; New York 12.229.9. Redrawn by Nathan Lewis.

There are no images of the phalanx, archaic or classical, that illustrate the traditional views regarding the part played in the battle by the rear ranks in either adding weight to the phalanx or pushing on the front ranks.

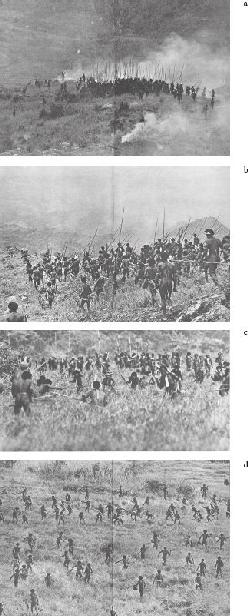

As an alternative to the classical phalanx as a model for the style of fighting adopted by hoplites in the archaic age, van Wees has suggested an open and fluid kind of combat often attested in “primitive” warfare. He illustrates this with the particular example of battles as they were still fought in the 1960s by warriors in the Highlands of Papua New Guinea.

A series of remarkable photos

32

illustrates their fighting techniques.

Before combat, Highlands warriors gather round their leaders in dense crowds [

fig. 2-11a

] and after a harangue set off at a run towards the battlefield, scattering as they do [2-11b] and slowing as they draw closer to the enemy [

2-11c

], until they come within firing range of the opposing lines. At this point the warriors are widely dispersed [

2-11d

] and in constant movement, not only across the front line ‘to avoid presenting too easy a target,’ but to and from the front: ‘men move up from the rear, stay to fight for a while, and then drop back for a rest.’ Warriors fight as archers or spearmen as a matter of personal preference. Spears, as in Homer, are used both for thrusting and throwing. At any one time, only about a third of each army takes an active part in the battle, while two-thirds stand or sit well back and observe the action. In the course of a day’s fighting, a man spends much time at the back, but he will also go several times to take his turn at doing battle.

In the course of this open order skirmishing, ‘the front continually fluctuates, moving backwards and forwards as one side or the other mounts a charge’. ‘As the early afternoon wears on, the pace of battle develops into a steady series of brief clashes and relatively long interruptions…. An average day’s fighting will consist of ten to twenty clashes between the opposing forces’, lasting between ten and fifteen minutes each.

33

Van Wees argues that, in essence, this model fits the depictions of combat in Geometric and archaic art, and the descriptions of battle in the

Iliad

(as well as the allusions to battle in the seventh-century martial poems of Callinus and Tyrtaeus); he concludes that this is also how archaic hoplites actually fought.

Whether this “primitive” model is viable depends largely on one’s interpretation of hoplite equipment. The Papua New Guinea Highlanders do not carry shields or swords, or wear body armor, so that they are certainly more mobile and more dependent on missile fighting than were archaic hoplites. If one believes that the weight of their armor made hoplites largely immobile, that they fought only with thrusting spears, and that the double-grip shield was designed for use in dense formations, then they clearly cannot have fought in the Papua New Guinea manner. If however one believes that hoplites were relatively mobile despite their armor, that the double-grip shield and the rest of the bronze panoply could be effectively used also outside dense formations, and finally that hoplites used throwing as well as thrusting spears in the seventh century and mingled in combat with archers and infantry carrying lighter Boeotian shields, as the vase paintings suggest, then it is conceivable that they practiced a rather slower and denser form of Papua New Guinea combat.

FIGURE 2-11. Battle in the Highlands of Papua New Guinea.

Source: R. Gardner and K. G. Heider,

Gardens of War: Life and Death in the New Guinea Stone Age

. (Harmondsworth, 1974).

Notes

1

. Hans Van Wees “The Development of the Hoplite Phalanx: Iconography and Reality in the Seventh Century,” 128, in Van Wees, ed.,

War and Violence in Ancient Greece

(London, 2000), 125–66; drawing (c) after a terra-cotta plaque, c. 520–510 BC, from Athens (Acropolis Museum 1037; photo in J. Charbonneaux et al.,

Archaic Greek Art

[London 1971], 313, fig. 359); (d) after an Attic red-figure cup, c. 520–510 BC, from Chiusi (Louvre G25; photo in P. Ducrey,

Warfare in Ancient Greece

, New York, 1986), 120, pl. 84.

2

. Van Wees (2000, 127).

3

. Van Wees (2000, 130–31).

4

. Victor Davis Hanson, “Hoplite Technology in Phalanx Battle,” in Hanson, ed.,

Hoplites: The Classical Battle Experience

(London, 1991), 63–84.

5

. Peter Krentz, “The Nature of Hoplite Battle,”

ClAnt

4 (1985), 50–61; Krentz, “Continuing the

Othismos

on

Othismos

,”

AHB

8 (1994), 45–49.

6

. Van Wees (2000, 131).

7

. A. M. Snodgrass,

Arms and Armour of the Greeks

(Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1967), 51, explains the significance of the helmet’s craftsmanship: “To beat a complete head-piece out of one sheet of bronze has always been a feat requiring exceptional skill on the part of the smith; in the seventeenth century AD, for instance, armourers seem to have lost this art, and resorted to constructing helmets in two or more pieces with a join over the crown; while even in 1939 a modern Greek artificer, making a replica of a similar form, found it difficult to beat out the back of the helmet unless a deep recess was left over the forehead. So far as we can tell, the Greek bronzesmiths at the end of the eighth century had no foreign model or precedent for their achievement.”

8

. E. Jarva,

Archaiologia on Archaic Greek Body Armour

(Rovaniemi, 1995), 111–13, 124–80, with n. 10 below.

9

. Snodgrass (1967, 52–53).

10

. A. Snodgrass,

Early Greek Armour and Weapons

(Edinburgh, 1964), 86–88; E. Kunze,

Beinschienen. Olympische Forschungen

XXI (Berlin, 1991), 4–5 n. 10.

11

. Hans Van Wees,

Greek Warfare: Myths and Realities

(London, 2004), 50 n. 10.

12

. See, e.g., the Benaki amphora: H. Lorimer, “The Hoplite Phalanx,”

BSA

42 (1947), 76–138, pl. 19.

13

. Lorimer (1947, 94).

14

. Lorimer (1947, 95).

15

. Lorimer (1947, 85).

16

. Van Wees (2000, 140).

17

. Van Wees (2000, 140–42).

18

. Lorimer (1947, 104–5).

19

. Van Wees (2000, 142).

20

. Lorimer (1947, 104).

21

. Van Wees 2000, 142.

22

. Snodgrass (1964, 138).

23

. Snodgrass (1967, 58).

24

. Van Wees (2000, 136) quotes W. Helbig, “Über die Einführungszeit der geschlos-senen Phalanz,”

Sitzungsberichte der Königlichen Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften. Philosophisch-philogische und historische Klasse

, (Munich, 1911), 3–41.

25

. Van Wees (2000, 138).

26

. Van Wees (2000, 139).

27

. Van Wees (2000, 139).

28

. Van Wees (2000, 142).

29

. Snodgrass (1964, 138).

30

. Snodgrass (1964, 139).

31

. Van Wees (2000, 132).

32

. Originally published in R. Gardner and K. G. Heider,

Gardens of War: Life and Death in the New Guinea Stone Age

(Harmondsworth, 1974).

33

. Van Wees (2004, 154).

CHAPTER 3

Hoplitai/Politai: Refighting Ancient Battles

PAUL CARTLEDGE

I was myself at one time an actively engaged participant in the intellectual gymnastics that are, inevitably, the default mode for the study of early Greek hoplite warfare.

1

But, in or around 2001, I effectively retired from the lists.

2

So my involvement here is largely that of a former combatant, and interested spectator, somewhat bloodied by the latest thrusts and cuts of scholarly rapiers and bludgeons but yet largely unbowed.

Once, perhaps, “2001” might have conjured up images of Stanley Kubrick and futurology, but today it is all too gloomy retrospective visions of the destructive mayhem in New York City on 9/11, and its ongoing military consequences in Iraq, Afghanistan, and elsewhere, that weigh like a nightmare on our brains. I highlight our present circumstances, not just because war seems, like Jesus’ poor, always to be with us, but because all history is in Benedetto Croce’s sense present history: we historians of ancient Greek warfare cannot, however much we might like to, avoid bringing a present (though not, we trust, a viciously presentist) consciousness to bear on our strategic studies of the ancient Greek past.

I suppose the first thing that has struck me most forcefully as I have tried to review the scholarship on early Greek warfare of the past thirty years or so is the extent of the shift away from the more narrowly technical toward sociopolitical issues and approaches. The message that what we should aim to do ultimately is not “war studies” or “military history” in the abstract, but polemology, a totalizing history of war-and-society, seems to have been firmly driven home. Hence, presumably, all those collective volumes, excellent ones too, with that sort of a title.

3

From this welcome welter I should like to single out for special commendation, as the twin pioneers in the 1960s, Yvon Garlan of Rennes and my Cambridge colleague and fellow congressist Anthony Snodgrass.

4

Gratifyingly, for example, religion has begun to be given its due place in the story.

5

The other thing that strikes me palpably now is just how much work has been published recently on ancient Greek warfare—the Croce syndrome at work again, presumably.

6

What follows is intended as a continuation of our editors’ introductory lucubrations, a scene-setting attempt to frame the discussions or polemics that ensue. I shall

state what I take to be the most compelling or pressing issues, and sometimes too give an idea of what my own views of them are, and how they have or have not changed over the past thirty years.

7

But this remains above all a position paper, a thinkpiece.

8

To begin with, therefore, let me try to deconstruct the “rise” or evolution of the hoplite phenomenon (a question-begging catchall label). As I (still) see it, we have to deal with a number of concomitant and I should say causally related variables or factors: first, and above all others, and indeed most generally, an “accelerated dynamic” as it has been nicely called

9

toward the formation of poleis or citizen-states with distinct identities, distinct territorial boundaries (including those of the especially dynamic “conquest states” such as Sparta), and distinct political, legal, and administrative institutions, as well as some idea of collective—including, not least, military—action; and, second, such further enabling or conditioning phenomena as demographic growth, the emergence of written law, struggles for power between old and new elites, intensified interstate relationships, and, last but not least, changing forms of warfare, especially greater or lesser degrees of hopliticization.