Mergers and Acquisitions For Dummies (9 page)

Read Mergers and Acquisitions For Dummies Online

Authors: Bill Snow

Some deals involve other costs as well, including a real estate appraisal, an environmental testing, a database and IT examination, and a marketing analysis. Fees vary, of course, but all these functions likely cost anywhere from $10,000 to more than $100,000 apiece.

This section may seem a bit wide open, but nailing down the costs without knowing the deal is impossible. The best way to get a concrete estimate of a particular deal's fees is to speak with advisors and ask them to ballpark their expenses.

This section may seem a bit wide open, but nailing down the costs without knowing the deal is impossible. The best way to get a concrete estimate of a particular deal's fees is to speak with advisors and ask them to ballpark their expenses.

If you're worried about fees spiraling out of control, negotiate a flat fee, or a capped fee, from your advisors if possible. Not all will be willing to do this arrangement. If you get pushback, you can always agree that if the advisor does the work for a flat fee now, you'll give him the ongoing legal or accounting work post-transaction.

If you're worried about fees spiraling out of control, negotiate a flat fee, or a capped fee, from your advisors if possible. Not all will be willing to do this arrangement. If you get pushback, you can always agree that if the advisor does the work for a flat fee now, you'll give him the ongoing legal or accounting work post-transaction.

Paying off debt

One of the areas that Sellers often overlook is the debt of the business. Unless stipulated, a Buyer doesn't assume the debt. If a company has $5 million in long-term debt and the company is being sold for $20 million, the Seller needs to repay that debt, thus reducing the proceeds to $15 million.

Post-closing adjustments

Another area that Sellers often don't think about is the adjustments made to the deal after closing. Most often this is in the form of a

working capital adjustment,

which occurs when the

working capital

(receivables and inventory minus payables) on the estimated balance sheet Seller provides at closing doesn't match up with the actual balance sheet as of closing that the Buyer prepares at a later, agreed-upon date (usually 30 to 60 days after closing)

.

Buyer and Seller do a working capital adjustment to

true up

(reconcile) their accounts; this adjustment is typically (though not always) minor. If the actual working capital comes in lower than the estimate, Seller refunds a bit to Buyer (often by knocking some money off the purchase price). If the figure comes in higher than the estimate, Buyer cuts Seller a check.

Say Buyer agrees to pay $10 million for a business and that Buyer and Seller agree that working capital has averaged $2 million. If Seller's estimated balance sheet shows working capital to be $1.5 million, Seller has to provide Buyer with $500,000. With a working capital adjustment, Buyer just pays Seller $9.5 million rather than $10 million.

Why take working capital adjustments? Simply put, working capital is an asset, and if less of that asset is delivered at closing, Buyer is due a discount from the agreed-upon purchase price (and vice versa). Without a working capital adjustment, Seller would have every incentive to collect all the receivables (even if done at deep discounts), sell off all the inventory, and stop paying bills, thus inflating payables. Buyer would take possession of a business that has been severely hampered by the previous owner. Buyer then has to spend money to rebuild inventory and pay off the old bills and doesn't have the benefit of receivables.

Sigh . . . talking taxes

Sellers often forget that they likely face capital gains tax on the business sale. That's one reason Sellers generally prefer stock deals; a stock deal likely has a lower amount of tax. For many (but not all) Sellers, an asset deal exposes them to double taxation: The proceeds are taxed at the time of the sale at the company level, and then the owner pays again when the company transmits the proceeds to her. (Chapter 15 gives you the lowdown on stock and asset deals.)

Speak to your financial advisor about your specific tax situation.

Speak to your financial advisor about your specific tax situation.

Determining What Kind of Company You Have

As I state throughout the book,

Mergers & Acquisitions For Dummies

is primarily for Sellers or Buyers of middle market and lower middle market companies. But what exactly constitutes those types of companies, and how do you define other company types? The distinction has to do with size, most often revenues and profits.

Then you have the issue of critical mass.

Critical mass

is a subjective term, and it simply means size: Does the company have enough employees, revenues, management depth, clients, and so on to survive a downturn? Smaller businesses most often do not have enough critical mass to be of interest to acquirers. Capital providers who may be able to help finance acquisitions will have little or no interest, too. Although critical mass differs for different companies, in a general sense a company with $30 million in revenue and $3 million in profits has a better chance of surviving a $1 million reduction in profits than a smaller firm with only $500,000 in profits.

If you're thinking about chasing acquisitions or selling your business, understanding where your business fits is important. Who may be interested in acquiring it?

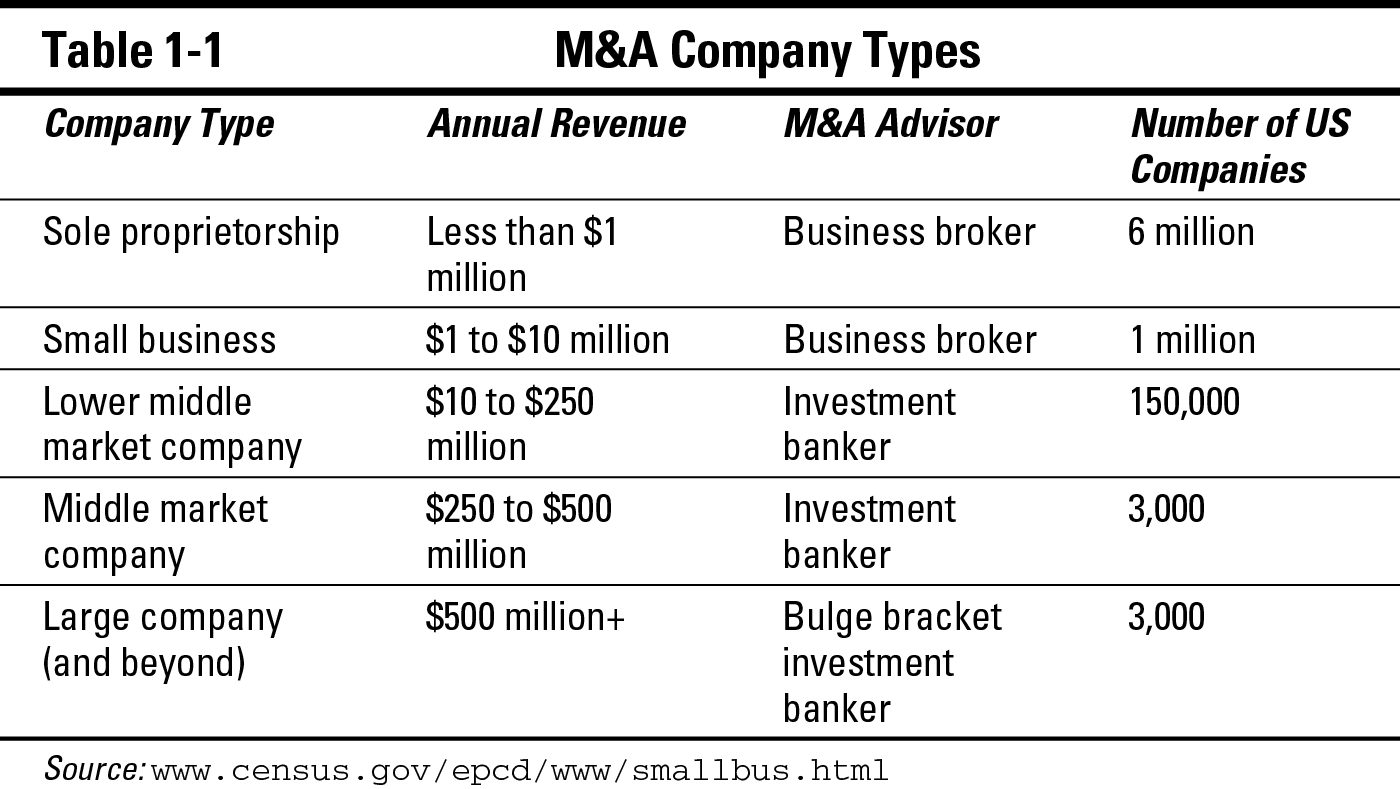

Definitions vary, but for the purposes of this book, I've divided the market into sole proprietorship, small business, lower middle market company, middle market company, and large company (and beyond). Table 1-1 defines these companies at a glance; the following sections delve into more detail.

Sole proprietorship

Sole proprietorships

are companies with revenues of less than $1 million. They're your neighborhood pizza joints, corner bars, clothing boutiques, or small legal or accounting practices.

Although these businesses are viable

going concerns

(aren't facing liquidation in the near future) and often trade hands, they're too small to be of interest to PE firms and strategic Buyers, as well as corresponding service providers who assist in M&A work. (Flip to the earlier section “Buyers” for more on these kinds of Buyers.)

Why are sole proprietorships of little or no interest to an acquirer? Simply put, buying a $1 million business and a $100 million business requires about the same amount of time and the same steps and expenses, so if you're going to go through the trouble of buying a company, you may as well get your money's worth and buy a larger concern. Making dozens of tiny acquisitions is just not worth the time or expense.

Small business

Small businesses

usually have annual revenues of $1 million to $10 million. These businesses are larger consulting practices, multiunit independent retail companies, construction firms, and so on. Unless the company is incredibly profitable (profits north of $1 million, preferably $2 million or $3 million), small businesses are too small to be of interest to most strategic acquirers and PE funds.

Although PE funds and strategic acquirers are usually not interested in smaller companies, they occasionally make exceptions if a company has a unique technology or process. In these cases, the acquirer can take that technology or process and deploy it across a much larger enterprise, thus rapidly creating value.

Although PE funds and strategic acquirers are usually not interested in smaller companies, they occasionally make exceptions if a company has a unique technology or process. In these cases, the acquirer can take that technology or process and deploy it across a much larger enterprise, thus rapidly creating value.

Middle market and lower middle market company

Lower middle market companies

are companies with $10 million to $250 million in annual revenue;

middle market

companies

have revenues of $250 million to $500 million. These companies typically have enough critical mass to be of interest to both strategic acquirers and PE funds. Also, because these deals are larger than small business and sole proprietorship deals, M&A transaction fees are large enough to justify the involvement of an investment banking firm.

Large company (and beyond)

Companies with revenues north of $500 million are considered large, huge, gigantic, and, if revenues are well into the billions, Fortune 500. Although transactions are typically very large, the fact is very few companies are large. The middle and lower middle markets are far larger.

Firms in this category typically use

bulge bracket

investment banks. These entities are the largest of most sophisticated of investment banks. They also charge enormous fees.

The term

The term

bulge bracket

originates from the placement of a firm's name on a public offering statement. Public offerings of securities typically involve multiple firms, and the largest firms, or managers of the offering, want their names to the left, away from the names of the smaller firms. The placement of the names looks as if they were bulging, hence the moniker.